Par

La grande histoire s’accompagne souvent de petites bassesses et Barack Obama vient récemment d’en faire la démonstration. Le 18 décembre dernier, soit le lendemain de son discours – prononcé simultanément avec celui de Raul Castro – annonçant une nouvelle ère des relations entre les Etats-Unis et Cuba, le président américain promulguait une loi visant à imposer des « sanctions ciblées aux personnes responsables des violations des droits humains des manifestants anti-gouvernementaux » qui, de février à avril 2014, avaient occupé les rues et monté des barricades dans quelques villes du Venezuela et tout particulièrement à Caracas.

Les promoteurs de la loi, en premier lieu le sénateur démocrate du New Jersey Robert Menendez, invoquent une quarantaine de victimes de la répression menée par les autorités. Ils oublient délibérément de mentionner qu’une bonne partie de ces victimes étaient des policiers et des militants chavistes et que le gouvernement avait fait arrêter au moins 17 membres des forces de sécurité contre lesquels il existait des présomptions d’actes de violence sur les manifestants. En fait, les ténors de l’opposition vénézuélienne avaient poussé leurs troupes à utiliser des méthodes insurrectionnelles pour provoquer le départ de Nicolas Maduro élu à la présidence en avril 2013 de manière parfaitement légale et transparente. Cette stratégie de la tension [1] s’inscrivait dans une longue série de mesures de déstabilisation du pouvoir bolivarien inaugurées par le coup d’Etat du 11 avril 2002 contre Hugo Chavez.

Dans le texte qui suit, le chercheur Alexander Main détaille les motifs de pure cuisine politicienne interne qui ont conduit Barack Obama à donner son feu vert à une loi en total décalage avec sa décision de renouer avec La Havane. Il s’agit tout simplement de donner un os à ronger aux plus exaltés des élus républicains et aux groupes d’exilés cubains d’extrême-droite afin de canaliser leur potentiel de nuisance au Congrès et dans l’opinion.

Ce pas en arrière dans la foulée du pas en avant des accords historiques du 17 décembre ne pourra que renforcer la solidarité des gouvernements latino-américains et caribéens avec le Venezuela, et mettre ainsi les Etats-Unis sur la défensive lors du prochain Sommet des Amériques prévu à Panama en avril 2015, alors qu’Obama aurait pu y être accueilli en chef d’Etat visionnaire. Il ne suffit pas de proclamer Somos todos Americanos…

Notes

[1] Lire Maurice Lemoine, « Stratégie de la tension au Venezuela »

One step forward, one step back in US-Latin America policy

President Obama’s decision to normalize relations with Cuba has grabbed headlines and drawn plaudits from around the world. In a short but historic speech, Obama announced a breathtaking series of measures including the reestablishing of full diplomatic relations with Cuba and the significant easing of restrictions on travel to the island nation. He also made a plea to Congress to undo the 54-year-old embargo against Cuba.

But at the same time, Obama has supported a significant hardening of policy toward one of Cuba’s closest allies in the region.

Venezuela has just joined Cuba as one of only two countries in the Western Hemisphere subject to U.S. sanctions. Legislation mandating sanctions against Venezuelan officials was approved by voice vote in the Senate on Dec. 8 and then sailed through the House on Dec. 10. On Dec. 18, just one day after his speech on a « new course » on Cuba, Obama signed the sanctions bill into law. Cuban-American Sen. Bob Menendez (D-N.J.), who authored the legislation, called it « a victory for the Venezuelan people. »

The trouble is, the people of Venezuela don’t seem to agree with Menendez. A survey carried out by independent pollster Datanalisis showed that nearly three quarters of Venezuelans oppose U.S. sanctions. The Caracas-based human rights organization PROVEA — a frequent critic of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro — also vigorously rejects the measure. Other Latin American governments oppose the sanctions as well. At a May summit, South America’s heads of state strongly voiced their opposition to the Senate bill and its House companion, authored by Florida Republican Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen.

The stated purpose of the bill is « to impose targeted sanctions on persons responsible for violations of human rights of antigovernment protesters » that took to the streets between February and April of this year demanding Maduro’s departure. The bill’s promoters mention that over 40 people died during the protests but don’t acknowledge that a large number of these deaths included state security forces and pro-government activists and were caused by the protesters themselves. Moreover, as human rights organizations have noted, Venezuelan authorities have carried out investigations of abuses and apprehended at least 17 security agents allegedly implicated in violent acts against demonstrators.

Troubling reports of impunity still surround some of the killings and abuses perpetrated during the protests. But does Venezuela’s human rights situation really justify sanctions ? If so, then why hasn’t the U.S. government sanctioned authorities in Colombia, where the army reportedly executed at least 5,763 innocent civilians between 2000 and 2010 ? Why hasn’t it sanctioned Honduras, where security forces regularly commit extrajudicial killings with impunity ? Or what about Mexico, where 43 students recently disappeared, most likely all killed, with the alleged complicity of both local and federal police ? Instead of penalizing the governments of these countries, the U.S. continues to send them hundreds of millions of dollars in security assistance.

So where do the sanctions against Venezuela come,from ?

For years, a handful of members of Congress with ties to far-right Cuban exile groups has sought to harden U.S. policy toward Venezuela and other left-leaning Latin American governments with close relations to the Cuban government. In 2007, Ros-Lehtinen and three other South Florida representatives sent a letter to President George W. Bush, urging him to declare Venezuela’s democratically elected government a « dictatorship » and grant temporary political asylum to Venezuelans who had overstayed their U.S. visas. In 2008, Rep. Connie Mack (R-Fla.), Ros-Lehtinen, Rep. Mario Díaz Balart (R-Fla.) and five other legislators sponsored a resolution calling for Venezuela to join Cuba on the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism.

Though these and other efforts didn’t gain momentum, the sanctions legislation, introduced in both houses in March, benefited from intense media coverage around the 2014 protests and an unprecedented mobilization of opposition-aligned Venezuelans in the U.S. It passed the House in May but was held up in the Senate until early December. The administration, meanwhile, announced that it opposed sanctions since, in the words of a U.S. official, it « would reinforce the narrative of this being about the Venezuelan government standing up to the U.S. »

A group of Democratic legislators applauded the administration’s position, noting that « unilateral U.S. intervention and sanctions have caused deep resentment throughout Latin America. » This is perhaps especially true in Venezuela, where people still remember how the U.S. government supported a short-lived military coup against late President Hugo Chávez back in 2002.

Nevertheless, the administration began carrying out minor, unofficial sanctions — first revoking visas of Venezuelan officials and then barring U.S. exports of equipment with a « military end use » to Venezuela. Then, in late November, Antony Blinken, Obama’s nominee for deputy secretary of State, told Sens. Menendez and Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) that the administration was now fully supporting sanctions.

The administration clearly dislikes President Maduro but is well aware that an aggressive unilateral measure like sanctions could undermine the divided Venezuelan opposition and further isolate the U.S. regionally. So why is it now supportive of sanctions ?

When Obama announced the dramatic shift in U.S. policy toward Cuba, he knew it would trigger outrage in the ranks of Cuban-American members of Congress. Though some of these legislators have fringe viewpoints on Latin America, they happen to have powerful committee positions and could make it even harder for the administration to achieve anything in Congress. The president apparently felt he should throw them a bone to try to appease them ; the bone was a promise to back their Venezuela sanctions bill.

Such trade-offs may make sense from a Beltway perspective. But allowing legislators stuck in a Cold War mentality to steer U.S. Venezuela policy is dangerous and risks wrecking the good will that the administration’s Cuba detente is generating throughout the region. In the words of President Obama, it’s time to fully « cut loose the [policy] shackles of the past. » Not just with regard to Cuba, but on policy toward Venezuela and other left-leaning Latin American governments as well.

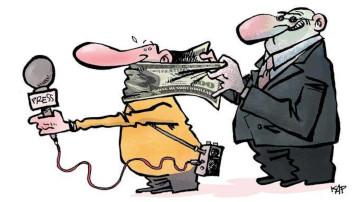

Illustration : Latuff