Maurice Stierl, University of Warwick for The Conversation

The story of the 19th-century underground railroad, a network of secret routes and safe houses helping enslaved African-Americans to escape, has received renewed interest over recent months. The railroad was run by activists who referred to themselves as agents, conductors and station masters, and to fugitives as passengers.

In May 2019, the Trump administration stirred controversy by delaying the release of the $20 bill featuring Harriet Tubman, a slave turned underground railroad activist and abolitionist. In November, the film Harriet was released, depicting the heroic struggle of the railroad’s most famous “conductor”.

But the underground railroad has also gained renewed attention in the context of precarious migration towards Europe and North America. Growing mass displacement caused by conflict, persecution, poverty or environmental destruction has coincided with tightening visa regimes and enhanced border controls. In response, forms of support and sanctuary for those on the move have spread.

In North America, such sanctuary and solidarity movements have grown since the 2016 election of Donald Trump. These movements uphold the underground railroad’s tradition and ethos by promising to support and hide those threatened by deportation. Some even facilitate migrant movements across borders, at times along the trails of the original underground railroad.

In Europe, comparisons to the underground railroad have also appeared, particularly since 2015 when over a million people crossed the EU’s external borders. This prompted some to talk of the Syrian underground railroad, French railroad “conductors”, or a transnational railroad across the Mediterranean.

Spirit of the railroad lives on

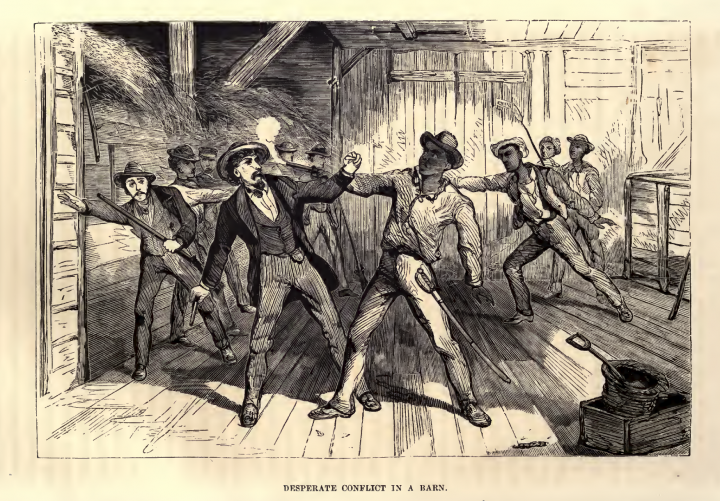

In a recent journal article, I explored these associations between past and present forms of fugitive escape and acts of solidarity. The 19th-century underground railroad was, according to the historian Eric Foner, “an interlocking series of local networks”, composed of “a small, overburdened group of dedicated activists”. Much of the activism of these so-called vigilance committees was not underground at all, but, in fact, very visible – fund-raising, mobilising the public, offering legal aid and confronting slavecatchers.

Read more:

Before sanctuary cities, here’s how black Americans protected fugitive slaves

This history of solidarity with those on the move was re-activated over a century later through the sanctuary movement in the US of the 1980s. A network of nuns, priests and their parishioners smuggled people from Central America, many of whom were fleeing US-supported death squads, into the US.

Today, the spirit of this activism lives on in countless ways, ranging from direct interventions along deadly borders, such as the the Mediterranean Sea, the Sonoran desert along the US border and Saharan desert in Africa, to providing guidance to those still trying to move. It also lives on in anti-deportation and anti-detention campaigns, and in networks creating sanctuary spaces and cities after arrival.

Denial of agency

When drawing these parallels between past and present forms of escape and support for those in flight, I noticed that in many accounts, the initiative of those escaping – both historic slaves and today’s migrants – is downplayed or ignored.

For the most part, slave fugitives in the 19th century could expect support from activists of the underground railroad only after they had moved north and crossed the Mason-Dixon Line, the boundary between slave states in the southern US and free states in the north. Retrieving slaves from the south and guiding them north, as Tubman did, was rare. For much of their journeys, slaves had to rely on their own ingenuity and strength as well as spontaneous acts of solidarity along the way, offered mostly by black people and communities not considered part of the underground railroad.

Similarly, the initiative of those migrating precariously today is often erased. Even in well-meaning humanitarian accounts, migrants are regularly portrayed as mere victims and denied any agency in their own migration projects. The activism and solidarity of people in the global south and diaspora communities is also erased – without their support many migrant journeys and border crossings would be even more dangerous. This means that many aspects of past and present underground railroads remain underground and unacknowledged.

This erasure of slave and migrant agency is also due to arguments developed by those opposed to the escape of “fugitives”. As I show in my study, both in the 19th-century US and in Europe today, those who support people on the move are blamed for causing such “illegal” movements. Back then, the phenomenon of slave runaways was wrongly attributed to “enticement” by northerners. Slave owners accused abolitionists of instilling the idea of flight in their “human property”.

Today, migrant escape is also often attributed to enticement by “northerners”. For example, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and activists working to rescue lives in the Mediterranean Sea are often wrongly constructed as a pull factor that encourages people to make the journey.

Read more:

NGOs under attack for saving too many lives in the Mediterranean

Politicians such as Italy’s Matteo Salvini, leader of the far-right League party and a former deputy prime minister, have derided NGOs for supposedly profiting from “loading this valuable cargo of humans – of human flesh – on board”. The country’s former prime minister, Matteo Renzi, also depicted migrant smugglers as “the slave traders of the 21st century”. Through these accounts, European politicians have sought to justify militarising the Mediterranean Sea and sending tens of thousands of migrants back to Libya, where their lives are in danger.

The story of the 19th-century underground railroad and the countless acts of escape and solidarity it symbolises serves as a reminder today that migrants, too, are seeking freedom, acting on their own needs and desires. At the same time, countless acts of solidarity along the way and forms of sanctuary upon arrival show that the ethos of the underground railroad lives on, even at a time when borders and social divisions seem to emerge all around us.![]()

Maurice Stierl, Leverhulme Research Fellow, University of Warwick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.