Wayne Dooling, SOAS, University of London for The Conversation

In its 2019 election manifesto, the Labour Party pledged to conduct an “audit of the impact of Britain’s colonial legacy”, with the goal of understanding “our contribution to the dynamics of violence and insecurity across regions previously under British colonial rule”.

Such a move would be welcome. A narrowly focused school history curriculum means that most Britons grow up with a limited knowledge of the history of the British empire and about the consequences for indigenous peoples in foreign lands. A view of the empire as essentially benign easily feeds into the sensibilities of a nation that believes itself to be bound by the rules of “fair play”.

Especially lacking is an understanding of how the British empire might appear from the perspective of the people who were conquered. The British empire is often seen as a force for good, as one that put an end to slavery and the slave trade, liberated foreign peoples from the tyranny of their rulers, replaced despotism with the rule of law and introduced millions to literacy, western medicine, commerce and Christianity. There are those in Britain today who greatly admire empire-builders such as Cecil Rhodes for their “sheer ambition, work ethic and self-belief”.

But the reality of empire was rather more complex and substantially less benign. The legacy of the British empire is more than a balance sheet of debits and credits.

My own research has focused on southern Africa, where Britain first showed a significant interest in the region as Dutch rule drew to a close at the end of the 18th century. The association of the ideology and practice of apartheid with Afrikaners, the descendants of Dutch settlers in South Africa, and the catastrophic rule of the ZANU-PF government in present-day Zimbabwe has allowed modern Britain to successfully distance itself from its role in colonial conquest, the making of white minority rule, and the ensuing poverty of Africans in the region.

Yet it was Britain that ensured that South Africa and Zimbabwe entered the 20th century as countries rigidly stratified and segregated along racial lines in which white minorities held political power at the expense of a disenfranchised African majority. Here the rule of law meant rule by white settlers in the interests of white settlers.

Violent from the start

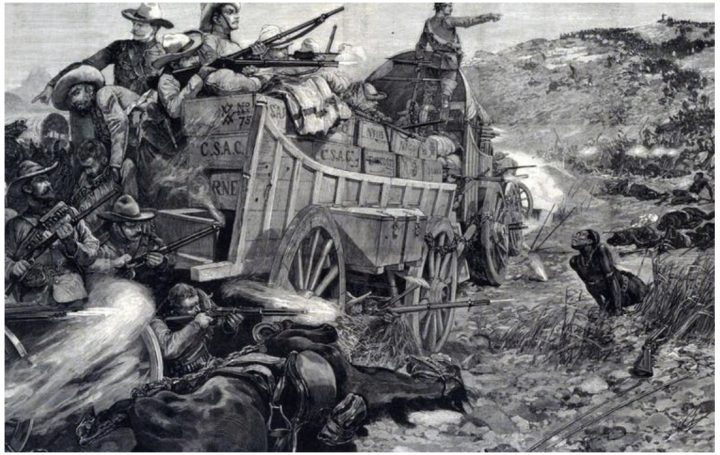

In the first instance, the British empire grew out of military conquest, a bloody business by its very nature. In southern Africa, as elsewhere, it was accompanied by substantial violence, frequent starvation, much misery, an untold number of deaths, and the mutilation of African bodies by British soldiers for the purpose of taking souvenirs.

Time after time – from the onset of British rule at the end of the 18th century through to the 20th century when political power was formally handed to white settlers – British armies and British arms came down on the side of white settlers. Colonial conquest involved the burning down of homesteads, humiliating and incarcerating African chiefs, dismembering once-powerful kingdoms, all the while making Africans bear the cost of colonial rule through an elaborate system of taxation.

Though the Zulu kingdom scored a decisive victory against Britain at the Battle of Isandhlwana in 1879, the “peace” of subsequent years witnessed the breaking up of the kingdom into several chiefdoms and the forced exile of the Zulu monarch. The kingdom’s material independence was eroded while its members were absorbed into the colonial economy as cheap labourers.

The Battle of Isandhlwana by Charles Edwin Fripp via Wikimedia Commons

In another example, the Ndebele of Zimbabwe lost somewhere between 100,000 to 200,000 head of cattle in the three years following the defeat of their kingdom in 1893, while settlers and police from the British South Africa Company armed with Maxim guns roamed the countryside helping themselves to whatever they could. Throughout the region, appropriated land was made available to white settlers, including thousands from Britain, while Africans were crowded into impoverished “reserves”.

Methods of barbarism

The South Africa War or Second Boer War between 1899-1902, a bitterly fought conflict between Britain and the Afrikaner republics, marked the high point of British imperialism in southern Africa. At the heart of this war was Britain’s desire to control the region’s mineral riches, especially the vast deposits of gold that were to be found in the South African interior and on which rested the value of the pound sterling.

Britain promised a speedy end to the war. Sure enough, the capital cities fell quickly to the British army, but the war entered a new phase when Afrikaner commandos turned to guerrilla methods of warfare, catching British units and columns off guard. Britain responded with “methods of barbarism”, a description that was used at the time by politicians and social campaigners in Britain.

Tens of thousands of Boer homesteads were torched and, as has been well documented by historians, thousands of women and children were forced into concentration camps. Towards the end of 1901 the mortality rate peaked at 344 per 1,000 people. An estimated 28,000 white people perished in the “death camps”, as they became known both locally and back in Britain.

Betrayal of black South Africans

Less well known is the fact that at least 10,000, but possibly as many as 30,000, black South Africans fought on the side on the British army while tens of thousands served in non-combatant roles. The fact that more than 100,000 black people were also interned was for a long time excised from the historical record. But recent research has shown that the concentration camps claimed at least 14,000 black lives – though there may have been as many as 20,000 black fatalities in the camps.

It was the manner in which peace was concluded that is most instructive. Those black people who served the British army during the war did so on the promise that a British victory would result in their equal participation in the political life of the country.

In the course of the war, Africans enjoyed great success in returning to ancestral land and so rolling back earlier decades of conquest. It was but a small step to expect Britain to honour these reclamations from Afrikaner landlords. But Africans were mistaken – once military victory was concluded, Britain moved quickly to disarm its black allies. Officials toured the countryside and put white landlords back in control of the land.

The political rights for which Africans had fought and died were not to materialise under British rule. Rather than honour the wartime promises made to their black allies, Britain chose to do business with the vanquished enemy. Foremost was Jan Christiaan Smuts, former Boer general and a man who so impressed members of the British establishment that he went on to become prime minister of South Africa and was named chancellor of the University of Cambridge in later life. To allow the “coloured races” the “casting vote”, Smuts believed, “would cause South Africa to relapse into barbarism”.

It is high time, then, that the history curriculum in British schools is expanded to examine the British empire in much greater depth. Labour’s pledge to audit Britain’s colonial legacy would also help raise awareness of the empire’s deadly toll.![]()

Wayne Dooling, Senior Lecturer in the History of Southern Africa, SOAS, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.