Radical. Transformative. Path-breaking. These cliches are often trotted out in the pages of party manifestos.

Manifestos are more than shopping lists of policy priorities and pledges. They represent an opportunity for political parties to put forward a narrative of reform and renewal of the underpinning purpose of the state. Of course, they are always couched in the rhetoric of change and innovation, but rarely do they move far beyond the technocratic exercises of tweaking existing arrangements.

Taken together, the Labour Party’s manifesto for the 2019 UK election breaks with this convention and seeks to transform the British state. It advocates no less than a new social contract between the citizen and the state.

This manifesto programme seeks to strengthen state capacity and develop the UK economy via a “national transformation fund” for critical infrastructure and low-carbon technology. The inspiration here is the developmental states of east Asia, such as Japan and South Korea. It is combined with the moral and political logic of the post-war Labour government led by Clement Attlee.

There is to be a turbo-charged council housing building scheme led by the state and major investment in health and education. Then, the part-nationalisation of broadband is an interesting mix of old and new. It sees the return of public ownership, but on the radically new terrain of internet access.

Here Labour is not only seeking to reverse some of the ravages of austerity but to fundamentally redefine what should be considered basic rights of citizenship in the 21st century. Access to the internet and digital services is being put in the same category of other essential utilities, such as water, energy, education and health – things that are too important to be left to the market.

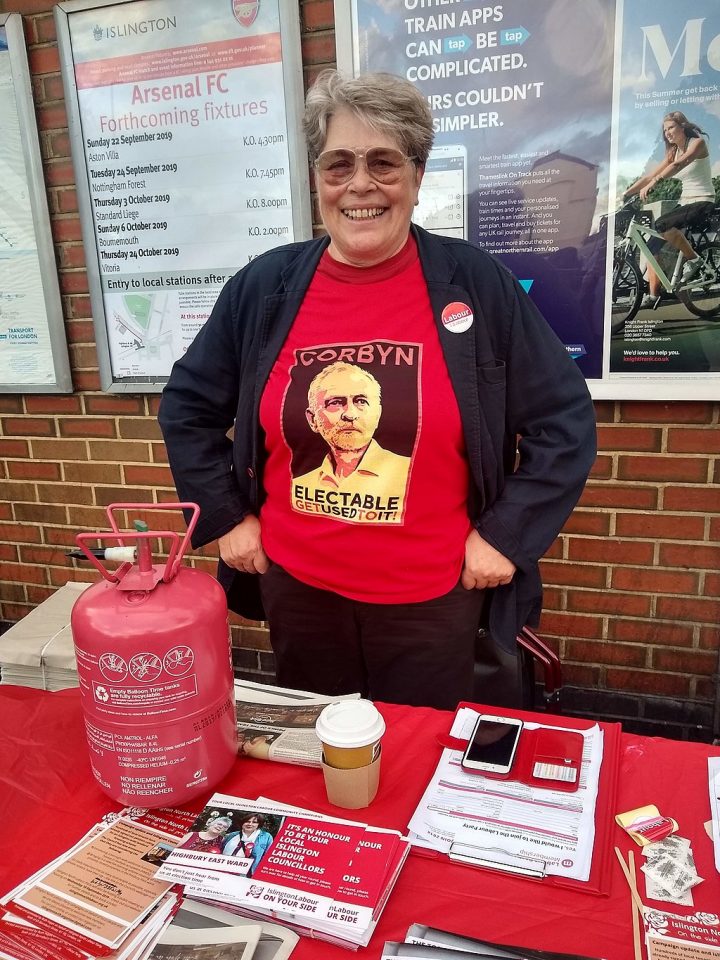

There is scepticism about whether such a radical, transformative agenda will resonate with voters enough to win the 2019 election. But even if it doesn’t, this manifesto has a longer term purpose. It is designed to be preference-shaping rather than preference accommodating. Its goal is to reframe the political debate on the party’s own terms, rather than dilute the radicalism of its proposals to appeal to anticipated affinities or the risk aversion of middle England. Under leader Jeremy Corbyn, Labour’s objective is to shift the centre ground of British politics to the left.

A surprising lesson from Brexit

Labour appears to have been emboldened to push harder on these issues by changes to electoral politics in the UK. For a whole new generation of voters, the New Labour years of the 1990s and 2000s – never mind Thatcherism – is a foreign country. As an ideological project, Thatcherism was designed to empower the market and irrevocably “roll back the frontiers of the state” through policies of privatisation, deregulation and liberalisation. The policies of Conservative governments in the 1980s and 1990s, and to a lesser extent New Labour after 1997, were premised on the assumption that state involvement in the economy leads to perverse results – of which the poor performance of nationalised industries in the 1970s was seen as indicative. Thus, the role of the state has gradually been minimised.

Younger voters know little more than the politics of austerity, as defined by public spending cuts and a shrinking state. Stark warnings about a return to the “bad old days of 1970s” when you had to “wait six months for the Post Office to put in a phone line” are hardly likely to mean much to a millennial employed in the gig economy whose working pattern is determined by an algorithm via an app on their mobile phone.

While a glaring registration gap between older and younger voters remains, a surge in the number of people under 25 registering to vote in recent weeks suggests a growing political engagement in this younger demographic and perhaps a more significant electoral impact this time round.

The other dynamic at play here is Brexit. Not only in the emerging electoral map based on the politics of Leave and Remain, but the undeniable evidence post-referendum that dramatic shifts in public opinion and the political culture of the UK are still possible. In these volatile, unpredictable times, the opportunity to reshape and remould the state and its relationship to the economy and the citizen is great.

In 2010, the Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government sought to fundamentally reduce the size and scope of the British state in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. That project was ultimately derailed by Brexit.

Political scientist WH Greenleaf famously characterised British politics as an enduring cycle between the politics of libertarianism and collectivism. While governing parties may change more or less each election, the prevailing ideological view of the state and its role is generally more sticky. It shifts episodically over time.

Whether Labour can confound the polls and win an outright majority is yet to be seen. But in a period of shifting political allegiances and hung parliaments, the manifestos of losing parties outside of government carry increasing weight and moral force.

After four decades in which economic liberalism and market logic have presided over British party politics, the 2019 Labour Party manifesto may represent a decisive swing of the pendulum back towards collectivism and an interventionist state – whichever party or parties form a government after the December 12.