By David Swanson

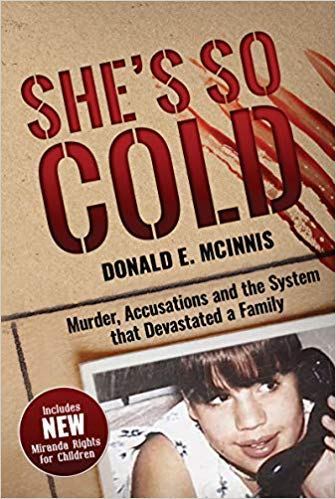

Donald E. McInnis’s book, She’s So Cold, is painful to read. McInnis was the defense attorney for one of three boys falsely accused of killing one of the boys’ sister. Much of the book is recreation of police interrogations that were videotaped, and of a court hearing.

This was one of those cases the mass media love and for which they effectively convict the accused in the minds of the public. This was in 1998 in San Diego, and the original victim’s name was Stephanie Crowe. But there were more victims, including Stephanie’s brother, two of his friends, and the three boys’ families. The trauma willfully and knowingly inflicted on them by the police and prosecutors was limited by the fact that so-called “confessions” by two of the three boys were videotaped. I haven’t watched the videos, but reading them is like watching violence in slow motion.

Some — O.K. basically everyone — would dispute my characterization of police behavior as “willful and knowing.” But I think the facts speak for themselves, and that it reduces human beings to unthinking objects to suppose them completely unaware of the most extreme pretenses and manipulations they engage in. Two of the boys have been awarded multi-million dollar settlements by the government for, I assume, something other than a well-intentioned accident.

For anyone who has managed to avoid the many accounts of how false confessions are created, and protected from reality a belief in the impossibility or unlikelihood of false confessions, this book is an excellent introduction. On the day that 14-year-old Michael Crowe’s beloved sister was brutally murdered, police began subjecting Michael to days of lengthy interrogation, denying him contact with his parents, falsely claiming that his sister’s blood was found in his room, suggesting to him that he might have a split personality and have murdered his sister without being aware of it, and threatening him with horrible punishment unless he admitted to what he had unknowingly done despite having no memory of having done it.

To understand why any reasonably intelligent 14-year-old might be won over by days of this interminable badgering, and good-cop/bad-copping, one must consider fear, exhaustion, and above-all an extreme and irrational faith in the absolute honesty of police. That last factor, the faith in police, is ubiquitous, and most people reading this hold it themselves, so we’re not supposed to call it irrational. But this “confession” and many others like it would not have been possible without that faith.

The irrational beliefs at the root of the tragedy recounted in She’s So Cold are not held by the three innocent boys, but by the police, prosecutors, corporate media, and public at large. They begin with the irrational belief that an unsolved crime is a failure. If a crime is committed and there is no persuasive evidence of anyone’s guilt, then how is the lack of a solution a failure? Who could possibly be blamed for it? If a reasonable, even fanatically extensive effort is put into gathering evidence, as happened here, and no guilty party is identified, where’s the blame? But in our culture, there is blame for such a thing, and it is directed at police and prosecutors. This madness contributed not only to the extensive efforts to make three kids “confess,” but to the defense of them presented by their lawyers. Central to their lawyers’ case was evidence that someone else, a man named Richard Tuite, actually committed the crime. Had the lawyers been unable to both point out the lack of evidence against their clients and also do the job of the police by demonstrating the likely guilt of someone else, their clients might have gone to prison.

Another irrational belief system that police may or may not fully believe in, but which they certainly act on, is that whoever they have targeted is lying. So, in reading these horrendous interrogation transcripts, we recognize that the kids, and even some of their parents, will believe the most absurd assertions from the police, because the police are believed to always tell the truth (even when they tell you, for example, that you are possessed by a demon who murdered your sister without you knowing it), but the police will not believe the most credible statements by those they have targeted for guilt, because such people always lie, and even tell gratuitous and superfluous and self-damaging lies. In this case, Michael told the police that he had gotten up in the night and gone to the kitchen for a drink, and not noticed his sister’s dead body in the doorway to her room. Great resources were devoted in this case to the question of exactly where her body had been and whether Michael would have seen it. But, had he been her murderer, he might have simply not volunteered that he got up in the night for a drink.

When the police began subjecting two of Michael’s young friends to the same treatment, they similarly isolated the kids from their parents, except when they were able to manipulate parents into helping them. By suggesting to a father that the best course was for his son to implicate the other two boys, they gained a powerful ally, thanks to the father’s irrational belief that baseless statements from police officers were gospel. The police tried to play each of the three families against the other two, falsely claiming to possess secret evidence, and that the other sides were squealing, and so forth, while in fact never possessing any evidence against any of their three victims. The police used pseudo-scientific tests to pretend to know that terrified children who were telling them the truth were lying. The children went on telling the truth while explicitly agreeing that they would lie if that’s what they had to do. And that was called a “confession.”

Are we to suppose that the capacity for self-doubt and correction has been eliminated from the police and their hired experts? They claim otherwise. They claim to have been objectively and without desired outcome pursuing the truth. They claim not to have been seeking admissions of a guilt they already believed in. Either they are lying about having taken that open-minded approach, or they were fully in control of their faculties when they manipulated frightened young people into “confessions.” They can’t have it both ways.

And what about the prosecutor who looked at the same police work that the defense attorneys and a judge found unacceptable, and chose to attempt to put three kids in prison? She, Summer Stephan, is now the District Attorney in San Diego. McInnis claims that she must have meant well, while simultaneously expressing a lack of understanding as to how she could have possibly meant well. I believe that in our observations of human behavior we are often far too reluctant to see extreme altruism and kindness and also far too reluctant to see cruelty and heartlessness and even sadism. If you cannot explain cruel behavior as well-intended, why assert that it must have been so?

At the end of his book, McInnis recommends a couple of steps that would certainly help prevent repetitions of this horror story. One is a Children’s Miranda Warning that is lengthier than that now used (or not used) for adults and children alike. It explains what the current Miranda Warning means, and adds to it the right to have your parents present. Another is a children’s bill of rights. It is specifically a bill of rights of the accused, and it limits the time of questioning a child to 4 hours in a 24-hour period, and establishes numerous other rights. I would add to this the fact that the United States is the one nation on earth that is not party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child which states that a child has the right “not to be compelled to give testimony or to confess guilt.” Why not join the world? Why not back the full range of rights, including some that might protect kids separated from their parents and locked in cages by fascist border patrols?

Beyond the creation of such rights and their defense, I think children (and adults) should be taught why they need them and how to employ them. The belief in inevitable and universal police honesty should go the way of beliefs in the inevitable honesty of war propaganda or campaign promises or religious scriptures. People should be taught to think, to be skeptical, to believe what’s proven, to trust where merited, and to be comfortable not knowing answers to questions that have not yet been answered.