From grassroots movements to presidential hopefuls, the importance of creating visionary plans for change is no longer being ignored.

Our country’s political discourse is becoming more interesting. On May 16, Washington governor and presidential candidate Jay Inslee released a progressive $9 trillion-plus “Evergreen Economy” plan.

By proposing a dramatic response to the climate crisis, Inslee joins a few Democratic presidential candidates already supporting the Green New Deal. Both proposals challenge the Democratic leadership’s rigid adherence to incrementalism and their belief that — no matter how urgent the problem — it’s best to avoid offending the 1 percent with policies that can make a difference.

We saw that principle operating in 2009 when Democrats controlled both Congress and the White House. Their response to an economy heading for the cliff: the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which focused on bailing out Wall Street.

When President Obama urged a second stimulus that would bail out Main Street in towns across the United States, his party refused. The Democrats thereby laid the groundwork for the Trump victory seven years later.

Incrementalism also stopped President Obama in relation to climate. The Recovery Act included some small support for renewable energy. President Obama asked then-Sen. John Kerry to put together a major climate bill. (The Democrats at that time had the majority in both houses of Congress.) Kerry tried, but could not get his Senate colleagues on board. The growing climate crisis wasn’t enough to risk their relationship with the economic elite.

How U.S. activists became so vision-averse

Historically, radical and progressive social movements that have made the biggest difference did their vision work — going beyond protest to describe the systemic changes that would result in more justice, peace and equality.

Even though the anti-vision “fearful ‘50s” had a hamstringing effect, the mass movements of the 1960s and ‘70s encouraged some growth of vision. School reformers re-imagined education, environmentalist and feminist writers generated utopias, black activists engaged in neighborhood renewal, community policing and alternative institution building. The vision work was not robust enough to stimulate a movement of movements, but growth did happen.

The widespread use of nonviolent direct action campaigns in the ‘60s and ‘70s put movements on the offensive and produced major victories. Alarmed, the 1 percent organized a counter-offensive.

In 1981 President Ronald Reagan fired a shot across the bow of the movements. He broke the air traffic controllers’ union, signaling what billionaire Warren Buffett later described to the New York Times as a “class war” that his class started.

In response, most progressive movements went on the defensive, trying to hold on to previously-achieved gains. Going on the defensive was a tragic mistake.

LGBTQ activists took the opposite strategy. ACT-UP led the charge with militant nonviolent campaigns against Big Pharma, hospitals and the federal government. These campaigns were followed by multiple LGBTQ demands including equal marriage, equality in the military and accessible toilets. While there has never been unity among us for a fully liberatory vision, a critical mass of LGBTQ people stayed on the offensive, with allies, for equal rights. We won victory after victory.

The sad story for most U.S. movements since 1980 has been defeat after defeat, which is to be expected when movements go on the defensive. The work of visioning correspondingly lapsed. Movements focused on protests instead of vision-led direct action campaigns, and popular culture trended toward dystopia.

The re-birth of visioning

The blockbuster “Black Panther” film signaled in popular culture a turn-around on vision. Artists created an Afro-centric utopia, and the popular response in 2018 was overwhelming.

Earlier, in 2016, social activists led the charge when the Movement for Black Lives issued its vision. Dozens of organizations signed on, even though the vision’s breadth and boldness meant that the signers wouldn’t necessarily agree with every sentence.

Also in 2016 came Solutionary Rail, envisioning a massive, solar-based reinvention of industrial transportation that would put new economic life into a rural America that the Democrats have abandoned. A year later, in 2017, Popular Resistance convened a gathering that wrote “The People’s Agenda,” which grew out of the work — and organizers involved in — Occupy Washington, D.C.

Those are just the ones I’m aware of. There may well be other collective vision-writing projects released in the United States that have escaped my attention.

Vermont initiates multi-level vision work

At about the same time, a Middlebury, Vermont “huddle” group concerned with climate was reading Naomi Klein’s book “No Is Not Enough,” which describes a Canadian visionary process known as The Leap Manifesto. The huddle turned to my book, “Viking Economics,” to learn about the role of vision in the Scandinavian social movements that waged successful nonviolent revolutions and are leaders in climate today.

The Nordics were emboldened by the early Nobel Prize-winning work of economist Gunnar Myrdal, who asserted that classical economics had its priorities all wrong when it came to capital and labor. Myrdal believed an economy should center ordinary people — workers, farmers and small shopkeepers — and use capital as a resource to further their well-being. His model was the opposite of “trickle down.” Take care of the grassroots, using capital for the common good. It’s OK to have a market, but regulate it highly and make sure a large part of the economy is owned by the people.

That’s the vision that makes the Nordic track record superior to free market capitalism, even in economic metrics: higher worker productivity, more start-ups, more patents, a higher percentage of the people in the labor force, and the virtual elimination of poverty.

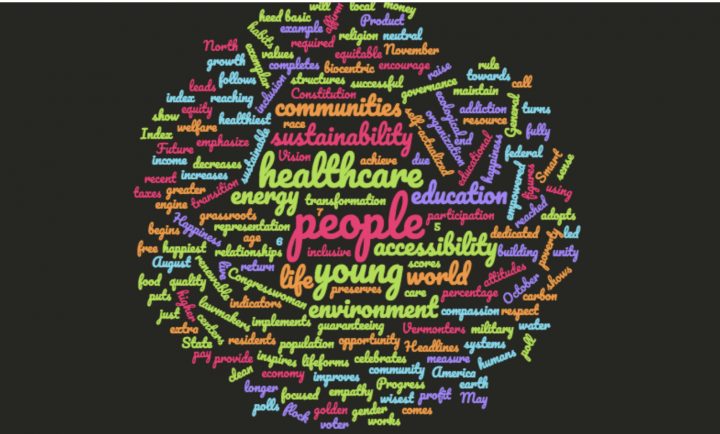

In 2018, the Middlebury huddle group organized a Vision for Vermont Summit, and over a hundred people from all parts of the state gathered for a weekend at Middlebury College to launch a visioning process.

This May, a year later, I went to Middlebury to join the Vermonters as they reviewed and celebrated their work. We heard from Middlebury professor Jon Isham’s students who interviewed small farmers, racial minorities, migrants and others who can easily be marginalized in the visioning process.

Their draft vision is broader than the Green New Deal but, in my view, the two are compatible. Middlebury’s Sunrise Movement is proposing to work with the Vision for Vermont group to go to the Vermont legislature with specific proposals related to the Green New Deal.

The Vermont process generated synergy from an activist/academic collaboration. Community organizer Fran Putnam, along with members of the huddle group, worked closely with faculty and students. The students found that the project built their skills and conceptual grasp, and realized their results have policy implications.

Activists and academics in other states may want to experiment with the model that seems to be evolving in Vermont. Not only are local thought leaders brought together on a state level to draft a vision, but an extra effort is taken to include marginal grassroots voices, through interviewing. The interviews can lay the foundation for relationship and further movement-building.

The state-level vision can be refined with an eye to the visions being developed on a national level, like that of the Movement for Black Lives. One question the drafters can ask is: “Now that we have our principles clear, what are the structures that need to be in place to implement the principles? For example, if we assert that health care is a right for all, what is our preferred structure to get that done?”

Some already-developed national visions will help to answer that question.

Vision work leads to even more practical outcomes when, as in Vermont, advocacy groups begin to generate specific proposals to take to state legislators. Legislative outcomes are often inadequate, the result of “sausage-making.” If, however, the proposals come from a larger, coherent vision grounded at the grassroots, and are backed up by a movement that knows the value of nonviolent direct action, they can accelerate to a living revolution.