For many, the Renaissance was the revival or “rebirth” of Western classical antiquity, associated with great artists painting the Sistine Chapel and the invention of the printing press in Europe. These local, European phenomena seem rather parochial compared to today’s world, where a hashtag on Instagram connects pictures across the world in an instant and aeroplanes take off every second from airports around the globe. Globalisation means that we can purchase a Starbucks coffee almost anywhere in the world and an enormous amount of goods available in Europe are made in China.

I’m an art historian, and so my interest in all this may not seem all that obvious. What do famous paintings by Italian Renaissance artists have to do with China or global trade? Art of the Italian Renaissance is often seen as the product of one culture — Italy — but in fact Italian art was the result of interactions with cultures from around the world. Our own experience of globalisation has led scholars such as me to look twice at Renaissance paintings – and the objects they depict – to consider whether a global, connected world is indeed a new thing.

Take Bellini’s Feast of the Gods, 1514, which has long been recognised as a masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance. This is a painting that was produced by the Venetian artist for the Duke of Ferrara, Alfonso d’Este. It depicts a scene of feasting set in the classical world.

This painting is part of a series commissioned by d’Este in 1511 for a suite of rooms that displayed his collections. The humanist Mario Equicola set the intellectual programme for the paintings and it is the classical subject matter that is usually discussed in relation to this cycle. The Feast of the Gods depicts an episode recounted in the first book of Ovid’s Fasti where ancient gods and goddesses hold a banquet. This seems a fairly straightforward depiction of a classical subject. But look a little closer and you will spot three pieces of Chinese porcelain, which might seem out of place.

It is generally thought that Bellini may have painted specific bowls he saw in Venice or ones that he had himself received from the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II when he travelled to Constantinople. But archival documents, which I recently published, have revealed that d’Este’s mother, Eleonora d’Aragona, also had a large art collection, including a significant amount of Chinese porcelain, which her son likely inherited. It is this collection that could very well be represented in the painting. It is likely that she received much of her porcelain as diplomatic gifts, through her connections to the international court of Naples.

Chinese porcelain was a sought after item by European princes in the 15th and 16th centuries. In the 15th century, blue-and-white Chinese porcelain did not come directly to Italy from China, but through Persia. It was then gifted to Europeans by the Mamluk and Ottoman sultans (rulers of what is now Syria, Egypt and Turkey). Porcelain was transported along the silk roads accompanied by other precious items sought by European rulers such as diamonds, precious gems, silk and spices. The fact that it had come from afar was part of its value, as was its association with trade, travel, and diplomacy.

Porcelain diplomacy

The cross-cultural associations of gifts are also evident in paintings of the magi – the ultimate example of gift-givers. Andrea Mantegna’s Adoration of the Magi, likely painted for d’Este’s sister Isabella d’Este, allows the viewer to feel as if they are a privileged member of this intimate ceremony.

Wikipedia. Public domain

This perspective also provides an opportunity for a close-up depiction of these rare gifts, which resemble the types of highly prized foreign luxury goods that would have been exchanged between rulers and found in the collecting spaces of the elite. The blue-and-white porcelain cup full of coins corresponds to one in Isabella’s inventory, for example.

The increased interest in collecting luxury goods within a secular context in the Renaissance might have been novel for Europeans, but it was not for Eastern rulers. Indeed, the collections of foreign courts – from the Mamluks and Ottomans in the Mediterranean, to the Aqqoyunlu and the Timurids of central Asia and Persia, to the rich empires in India and China – paled in comparison to European courtly collections. Eastern courts’ access to raw goods such as diamonds and gems and to the manufacture of luxury objects such as ceramics and metalwork meant that they served as models worthy of emulation. Possession of these items reflected the power and prestige of their owners.

Renaissance collections

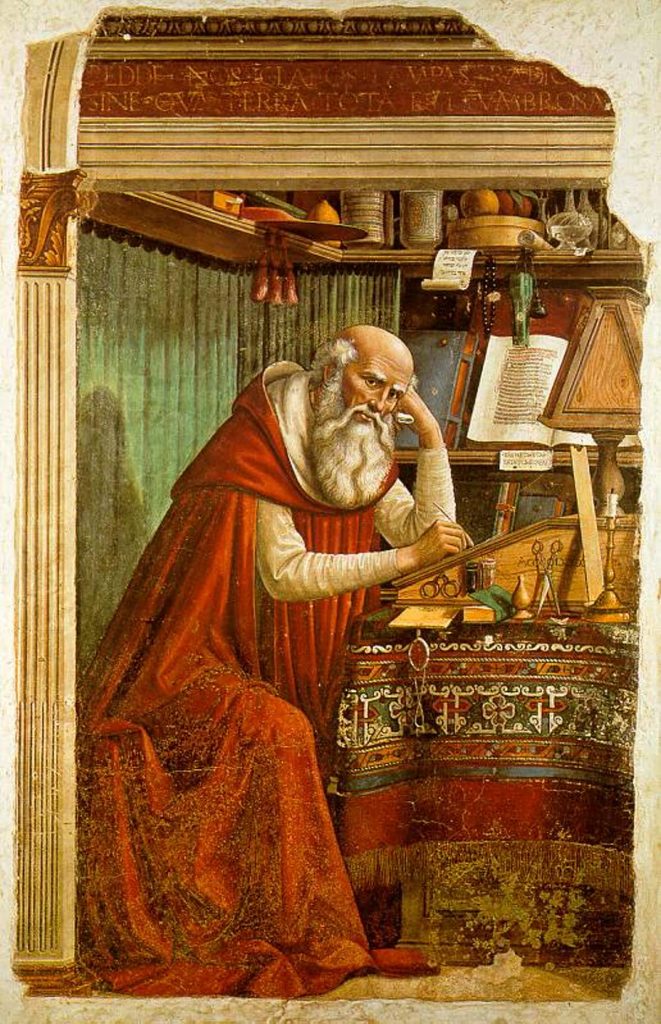

What did these Italian collecting spaces look like? The artist Domenico Ghirlandaio’s fresco of Saint Jerome from Florence is a quintessential illustration of the “Renaissance” studiolo – a sort of study or library – with its emphasis on learning and its reference to classical antiquity. But again, when looking more closely at the image, another story is told.

Wikipedia

An oriental carpet adorns Jerome’s desk and glazed albarelli (drug jars) and crystal vases grace the shelves. These point to an international luxury trade that stretched from China through Persia and across the Mediterranean. This was a world where glass mosque lamps were produced in Venice for export to Syria, where ceramic drug jars made in Valencia used tin from Cornwall, incorporated motifs found on Chinese porcelain, held spices from India, and were shipped across the globe.

Of course this isn’t akin to today’s globalised world, in which you can order something on the internet and have it shipped from one hemisphere to another in a matter of days. But what it does tell us is that cultures — and the products that they produce – have never been “pure”. States have always relied on cross-cultural interactions to access raw goods, as well as luxury items. And it is important to underline that this intermixing of cultures gave rise to destructive outcomes too. Power dynamics were often unequal, resulting in forced conversions and colonial domination.

The presence of Chinese porcelain in Italian Renaissance paintings tells us that the world, has in some ways, always been global. And looking again at these famous paintings might hold lessons for our perspective on globalisation today.![]()

Leah Clark, Senior Lecturer in Art History, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.