We have already published a brief article on the work of Opet Bosna for refugees and migrants held up at the border between Bosnia and Croatia. We discuss the issue in more detail with Marco Cicorella, one of the association’s founders.

You’ve just returned from a trip to Bosnia. What situation did you find there?

That’s right – we were there from 27 December 2018 to 2 January 2019. Accompanying us was a member of the Ospiti in Arrivo charity. Our main local partners were, once again, SOS Team Kladuša (SOS) and the Spanish organisation No Name Kitchen (NNK). The next trip is planned for mid-February with a 2,000 euro fundraising target.

Despite the sub-zero temperatures, the flow of arrivals into Bosnia has never stopped. It’s difficult to estimate figures, but according to official statistics from the Bosnian government and the IOM (International Organization for Migration), almost 23,000 people from Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Palestine, Bangledesh, Iraq, Yemen and the Maghreb entered Bosnia last year. Of these, however, only around 1,000 have made formal requests for asylum. Around a hundred have been subject to assisted repatriation. No one is keen to remain in Bosnia.

A policy of ‘easing’ the volumes of migrants arriving in Bihac has also been in place for some months, justified by the authorities on the grounds that they are unable to guarantee enough housing. Migrants found on trains, and in buses or taxis are either sent back to Sarajevo or abandoned in the middle of nowhere. They then leave the capital again, possibly by paying smugglers, to reach Bihac once more or Velika Kladuša.

Borici’s former student residence provided shelter to hundreds of refugees and migrants for months. The crumbling building was pulled down with the inhabitants moved to a government camp run by the IOM and the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) in collaboration with the Red Cross and other international non-governmental organisations. Between 1,800 and 2,100 people, of which at least one hundred are non-accompanied minors and a number of families with children, are forced to live there in overcrowded conditions.

Families, children and the vulnerable are also temporarily housed in Hotel Sedra, which has a capacity of 420 places, and other hotels. These too are run by the IOM, UNHCR and other non-governmental organisations. We have been told by Red Cross volunteers that once work to rebuild the Borici residence is complete, people will be transferred back.

People have also continued to arrive in Velika Kladuša (VK). Following protests at the border and the dismantling of the ‘swamp’, an improvised community of tents where hundreds of migrants lived, between 400 and 700 people have now settled in the former Miral factory. It is difficult to know how many children and families are there. Once again, it is the IOM and ACNUR, in collaboration with non-governmental organisations that run the camp.

Many people, especially the young, have begun to occupy abandoned houses. Everyone has made several attempts to cross the border with Croatia, but have returned after having been beaten and robbed by the Croatian police. Undaunted, they will try again: they call it the ‘game.’

This trip turned up something new: a first aid centre that was providing medical assistance to as many as 30-40 people a day, either with injuries from the Croatian police or burns from the use of makeshift stoves and fires in houses.

Bosnia has also seen the criminalisation of acts of solidarity

Unfortunately, this is true – just like in many other areas such as the Mediterranean, the UK, or on the border between France and Italy. The cost today of merely opening your own house to a refugee and offering a cup of tea or a shower can be a fine of up to 2,000 euro. On top of that, there are the deportation orders slapped on volunteers from independent associations working to improve the conditions of thousands of refugees. There is however a particular dynamic here: everyone knows what it is like to be a refugee escaping from war. That means that the vast majority of people are more welcoming and open than in Italy. Despite tensions, the critical situation and desperation of migrants – which can often lead to antisocial behaviour – very few Bosnians have given in to intimidation.

What do you need most?

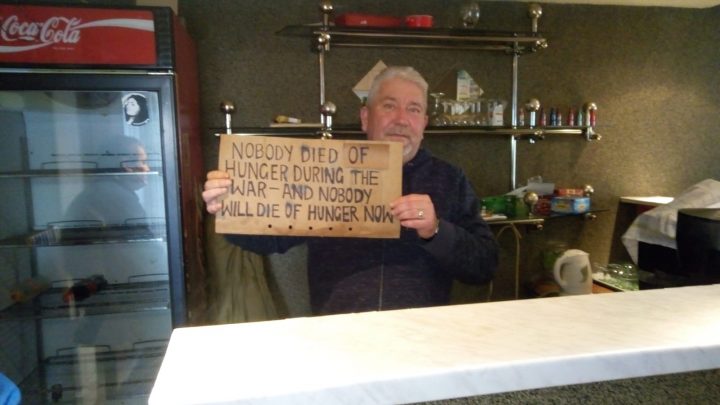

The donations we have received have mainly gone towards shoes and thermal socks, purchased directly in Bosnia, so as to avoid issues with customs, and to help the local economy. We have also bought food for the restaurant where SOS feeds 300-400 people every day. Lunch is prepared by a group of 5-6 Bosnians; the bar of the restaurant still displays a sign that says: “Nobody died of hunger during the war and nobody will die of hunger now.” As I said before, the recent memory of the war that affected the whole of the former Yugoslavia means that many people are helping to support those arriving in Bosnia.

In the restaurant’s basement there is also a Free Shop where migrants can receive linen, socks and toiletries and can choose clothes from those donated. The volunteers help them find what they need most. Being able to look in the mirror and choose the clothes you want rather than just taking whatever is available helps to restore a bit of dignity, humanity and cheer.

In your opinion, what can be done to help improve this inhuman, and still little-known, situation?

Several things, all of which are simple and easily done. The most pressing thing is to make a donation, which will allow us to buy what is needed. People can also take part in our trips, which are open to everyone, and allow you to see how this is not a remote problem, but one that concerns one of Italy’s neighbours. And when you meet someone in need, what do you do? Do you walk past that person and head straight on, or do you give them a helping hand?

It’s also important to know the facts: European reasoning dictates putting pressure on Bosnia (as it does on Greece) to keep refugees away and render them invisible, rewarding the country when it does this. As well as being inhumane, this logic is flawed – it won’t stop people coming, ever more desperate and frustrated. Either that, or they will die trying.

This is why organising public meetings where we can recount our experiences and report on the situation is such a great help. We need to talk about all these people fleeing from their countries. Men, women and children are held up and beaten at borders, hide out in the woods where there are landmines, bears and wolves, or are forced to pay thousands of euro to a smuggler in order to reach the so-called ‘cradle of civilisation.’ They are victims of the darkest chapter of our times, victims of Fortress Europe, and victims of our history. We want no part in this inhumanity.

What motivates you the most to carry on with your activities?

The reality is that every time we go back we feel like we received much more than we gave. It’s an intense experience, one that enriches you and makes you feel more alive and more open. You meet people happy to see you, who realise that not everyone is racist or hostile and you can create bridges and reassert the value of solidarity.

Translation from Italian by Malcolm Gilmour