Seventy years after Gandhi’s assassination on the streets of New Delhi, Ramachandra Guha’s new book, Gandhi: The Years That Changed the World, 1914-48, reopens a familiar debate around his legacy. What was Gandhi’s message? What were his politics? What can we learn from him today? And is he still relevant?

Guha, presenting the second half of a biography that began with his 2013 book, Gandhi Before India, offers a straightforward but detailed narrative in which “the Mahatma” negotiates a principled path between the warring political trends of the age. Historian of empire, Bernard Porter, welcomed Guha’s work and its subtle defence of a “gentler, more tolerant and consensual forms of politics” that is now, in the age of Donald Trump, Brexit and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, on the decline in the West and elsewhere.

Others are more biting. Fellow Gandhi scholar Faisal Devji charges Guha with neutralising the Mahatma’s radicalism. Meanwhile, author Pankaj Mishra, reexamining Gandhi’s writings in a “post-truth age” of “furious revisionism”, uncovers a “relentlessly counter-intuitive thought” left untapped by Guha’s tales of a “bland do-gooder”.

Resurrection

All these accounts, however, seek to resurrect Gandhi as a political mentor for today. Modern politics – and its new formula of Twitter hashtags, populist sloganeering and strongman dictators – may seem an unlikely place for the teachings of Gandhi to offer fresh inspiration. But just such a thing also happened during the Cold War, when politics faced some very similar problems.

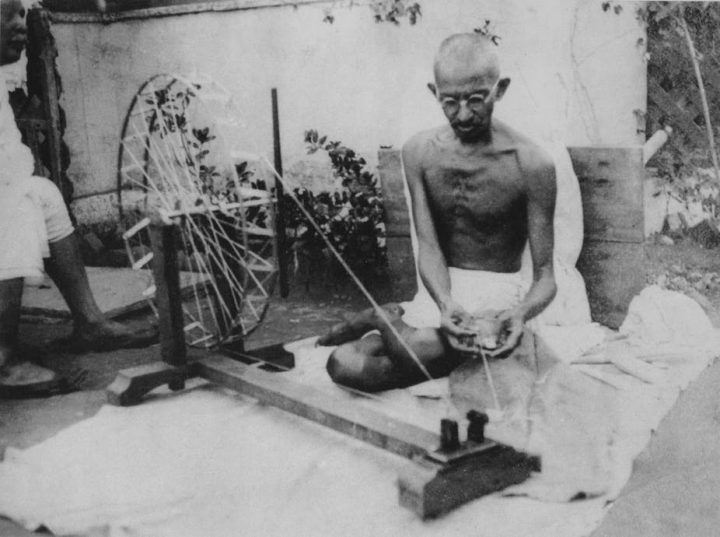

Gandhi is sometimes imagined sitting beside a spinning wheel pouring scorn on science and modernity. Indeed, when asked by a reporter what he thought of “Western civilisation”, he famously replied: “I think it would be a good idea.”

But his politics were more complex than this. Gandhi read the works of Western political thinkers including John Ruskin and Leo Tolstoy. India was being sucked into a global economy based on the exploitation and automation of labour. Industrial capitalism – and its partner, imperialism – only cemented uneven power relations and alienated one Indian from the next. He believed what was needed, instead, was a social and economic life based around local production for local needs, something that would also foster greater cultural enjoyment.

But is the current post-truth age still able to make use of this simple, authentic message?

A look into early 1950s Indian history provides some clues. When India achieved independence in August 1947 – with Jawaharlal Nehru as its first prime minister – Gandhi, it is supposed, remained as a spiritual and moral, rather than political, guide. His vision of a “village India” died in 1948 with his assassin Nathuram Godse’s bullet. And as Cold War ideological competition ramped up between communism and capitalism, rapid and centralised economic growth seemed inevitable.

In sponsoring conferences and magazines in which these intellectuals could articulate their views, the CIA hoped it could channel their anti-authoritarianism to a useful Cold War end. But this did not work out. CCF branches often acted as repositories for radical aspirations which could find no other home.

The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom (ICCF), formed in 1951, was a striking example. Freedom First, its maiden publication, eschewed cultural criticism for discussions of domestic politics. The CCF’s push for the formation of a new journal, Quest, which reversed this was in vain, with one writer taking the opportunity to rail against a Westernised Indian “ruling class” whose interest in state-led development was bound to create “a situation reminiscent of the looking-glass world” – in other words, to impose Western ideologies onto India.

A stateless society

These writers – often former freedom fighters who had gone to prison for their travails – wanted a new egalitarian politics they sometimes termed “direct democracy”. Views on how this should be approached varied, and as the decade wore on, some took to advocating for a pro-capitalist, if also welfare state-friendly, programme.

Others, though, found in Gandhi a source of optimism. In 1951, Vinoba Bhave and other social reformers committed to Gandhi’s “sarvodaya” – progress of all – concept, founded the “Bhoodan Movement”. This was aimed at encouraging landowners to redistribute land without violence and rapidly reduce inequality in agrarian India.

This fascinated the ICCF. Marathi trade unionist and columnist, Prabhakar Padhye, named Bhoodan one of several reform movements capable of constituting “a new social force in the life of the country”. The ICCF’s annual conference welcomed the movement, with speakers calling for a “Gandhian” politics which made “cooperation, rather than competition, the rule of life”.

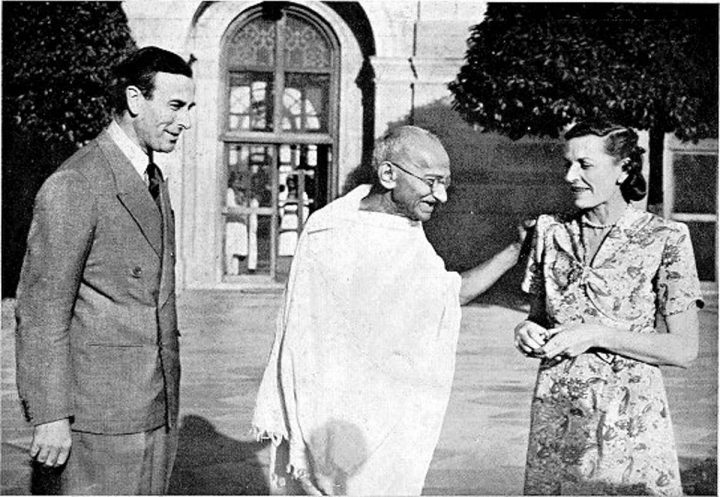

Via Wikimedia Commons

Soon, key ICCF writer, Minoo Masani, reported on a tour undertaken around the Indian state of Bihar with fellow member Jayaprakash Narayan. Speaking with crowds of peasants and rural poor, Narayan bracketed together totalitarianism and the welfare state as inherently coercive. What the pair supported was “Gandhism” – or a more spontaneous and participatory politics which “like anarchism or communism, visualises ultimately a stateless society”.

The point is that these intellectuals were drawing on Gandhi in defiance of an oppressive global political climate and its relentless classification of different ideas and visions as good or bad, communist or anti-communist, modernist or traditional.

In its vacuous rhetoric and sleazy sloganeering, the early Cold War era was like today. And then, as now, Gandhi’s ideas were of renewed interest. As we now face a global dearth of alternative political ideas, perhaps it’s no wonder we are turning again to the Mahatma for inspiration.![]()

Tom Shillam, PhD Candidate in History, University of York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.