By Zoe Sullivan1,

reproduced from Public Banking Institute, Sept. 04, 2018

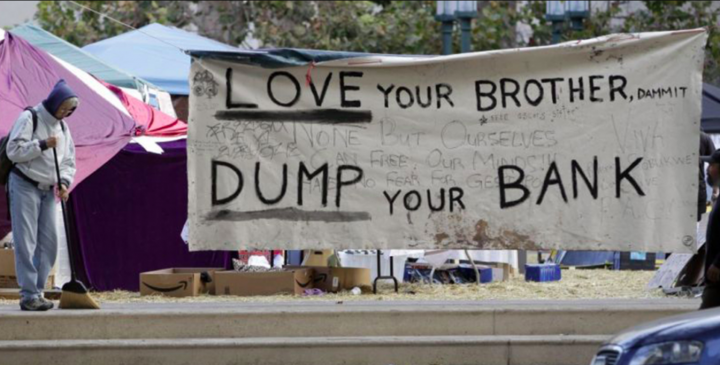

Ten years after the most recent financial crisis, some argue we have learned nothing, but a movement across the country to establish public banksshows how some have taken its lessons to heart.

Inspired by North Dakota’s century-old public bank, Oakland is joining with its neighbors — Richmond, Berkeley, Alameda County — to explore how they might establish a regional public bank, meaning a bank that would be co-owned by the four local government bodies, which would serve the public in a way many feel privately-owned banks have not.

Meanwhile, statewide, California has a coalition of cities interested in establishing locally-accountable, ethical banks owned by government bodies, known as public banks. Now, Oakland joins San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Portland, Philadelphia, and New York City along with New Jersey and Michigan in the quest to establish socially-responsible, government-owned financial institutions that can fulfill public missions.

“The various issues related to banking problems in our communities are interrelated,” says Rebecca Kaplan, at-large member of Oakland City Council. “Part of the motivation for why we need a public bank comes from this work around banking discrimination.”

Before being elected to office, Kaplan worked in the City Attorney’s office on predatory lending issues.

“People were told they were going to pay two percent interest, and they would show [the borrowers] calculations about how little per month they were going to have to pay,” she recalls from her time at the City Attorney’s office. But the paperwork hid in the footnotes how this rate would increase dramatically over time, she says, “And this was done to thousands of people in Oakland — disproportionately to people who did not speak English, who were given documents in English to sign, including widows being targeted in their moment of vulnerability.”

The Wells Fargo fake accounts scandal was another blow to the banking sector’s credibility. The Friends of the Public Bank of Oakland underscore that one of the project’s main goals is to divest from Wall Street given its support for the fossil fuel industry.

The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis estimates that about $458 billion in deposits come from state and local governments. State and local pensions systems, meanwhile, account for nearly $4 trillion in investments. That means public banks holding these assets would have substantial financial clout, although those figures are just fractions of the overall banking system’s $12 trillion in deposits and $17 trillion in assets.

YaVette Holts, founder and executive director of the Bay Area Organization of Black-Owned Businesses, known as BAOBOB, agrees that support for a public bank comes from frustration with injustice.

“People came together after Ferguson to think about what we could do to take our money out of this system and keep it in our communities,” says Holts. Those conversations, she says, led to the birth of BAOBAB. When she learned about the public bank initiative, Holts says it was clearly a natural fit.

“[A public bank] would create a resource of funding that would be accessible to our constituents for major things like buying a home or starting a business,” says Holts.

“In light of the gentrification that’s going on,” she adds, Oakland needs to, “step up and help the populace with something like this.”

After reviewing and releasing a public bank feasibility study, the Finance and Management Committee of Oakland City Council voted on Sept. 11 to forward the matter of establishing a public bank to the full council.

Cathy Jackson-Gent, whose firm, Global Investment Company, drafted the feasibility study, told Next City that two of the challenges facing the project include the financing for the institution and the risks posed by the local cannabis industry.

Although cannabis is now legal in California, it remains a narcotic under federal law. Jackson-Gent explains that the feasibility study had recommended that the bank not engage with the cannabis industry because of the risks associated with this discrepancy between state and federal law.

“On the federal level, cannabis is an illegal substance, and so any associated cash transactions are considered money laundering on a federal level,” says Jackson-Gent.

The California Growers’ Association and the U.S. Department of Treasury did not respond to requests for an interview for this article. Nor did Harborside, a large marijuana dispensary based in Oakland.

To minimize the risks associated with taking deposits from the cannabis industry, one approach Jackson-Gent describes would be to create two different banks: one focused on depository services and the other a state-chartered “infrastructure bank” that would serve the cannabis industry exclusively.

While cannabis brings some sticky issues to the table, financing the bank itself is another critical issue to address. Paul Pryde, formerly the chief consultant to the U.S. International Trade Administration on loan guarantees, is now a member of Friends of the Public Bank of Oakland.

“You’ve got to find ways to do this without stretching Oakland’s budget,” Pryde says, explaining how the public bank can’t become a competing budget item with existing city services.

“One way to do it is to get capital from other state or local organizations that have interests aligned with your own,” Pryde says. He points to California’s Air Resources Board, which has approximately $1.5 billion in annual income from cap and trade auctions.

Pryde also explains how the initial influx of capital from local government owners would only need to be a fraction of the public bank’s full capacity to lend and invest in communities.

“Under current banking rules, for every 10 dollars in [loans and other investments], it has to have a dollar in capital [from its owners],” Pryde explains. “If you put a dollar into the public bank, it can make ten dollars’ worth of financing for renewable energy and other projects.

“This hasn’t been approved by the regulators,” Pryde cautions. “But they’re ideas that I think worth exploring mainly because they have to potential to bring in significant amounts of money without stretching local budgets.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: The original version of this article incorrectly described the services provided by the proposed public bank in Oakland. We’ve corrected the error.

1 Zoe Sullivan is a multimedia journalist and visual artist with experience on the U.S. Gulf Coast, Argentina, Brazil, and Kenya. Her radio work has appeared on outlets such as BBC, Marketplace, Radio France International, Free Speech Radio News and DW. Her writing has appeared on outlets such as The Guardian, Al Jazeera America and The Crisis.