Joseph Downing, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) and Richard Dron, University of Salford for The Conversation

For those who were present in West London on June 14, 2017, it’s a day they will never forget. Residents awoke to the smell of fire and the sound of helicopters, while exhausted, blackened firefighters laboured in the streets surrounding a burning tower block. Questions rapidly emerged about how Grenfell Tower, a local landmark – for many a “vertical village” – had become a deathtrap.

In the hours and days that followed, uncertainty about the number of casualties and the cause of the fire endured. Social media platforms such as Twitter became a place where survivors, civilians, journalists and aid organisations shared the latest updates about the cause of the blaze, its progress and its aftermath.

But remember, this was the summer of 2017: at the time of the fire, terrorists linked with Islamic fundamentalism had mown down pedestrians in Stockholm and London (twice, shot a police officer in Paris and planted a bomb in a Manchester stadium – each time, claiming lives. There were stories of jihadists travelling from Britain to join so-called Islamic State – some of whom hailed from the same area as Grenfell Tower.

Combined with the fact that many of those who lived in Grenfell Tower were Muslim, their role – and the role of British Muslims more broadly – became a focal point of the online debate surrounding the tragedy. In the four days days after the fire, 44,000 tweets with the keywords “Grenfell” and “Muslims” flooded the social media platform. We decided to analyse these tweets, to see how Muslims were perceived and portrayed in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire.

A helping hand

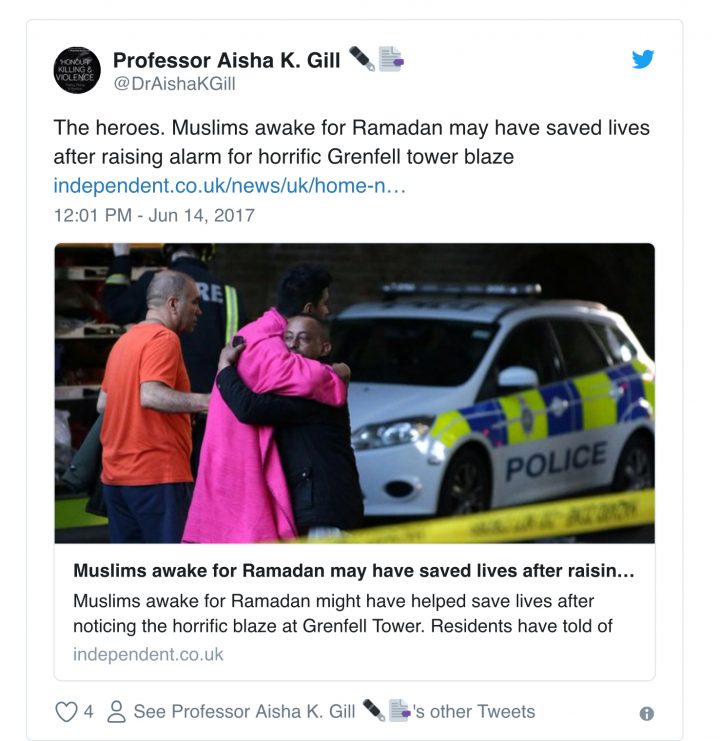

Our initial search of the tweets revealed that, during the first hours of the fire, there were tweets discussing the possibility of the fire being a terror attack. Some speculated that Muslims had set the fire as an attack during Ramadan. But there was also a substantial number of tweets depicting Muslims as heroes during the fire, because they were awake during Ramadan to raise the alarm, and knocked on doors to get residents to safety, while the “stay put” advice was still being given by the emergency services.

We wanted to go deeper into the data, to find out how certain messages were spread, and identify the key “influencers” who shaped the debate. We purchased the data from a third party data provider, and analysed the text using a specialised platform with machine learning capabilities, called discovertext.

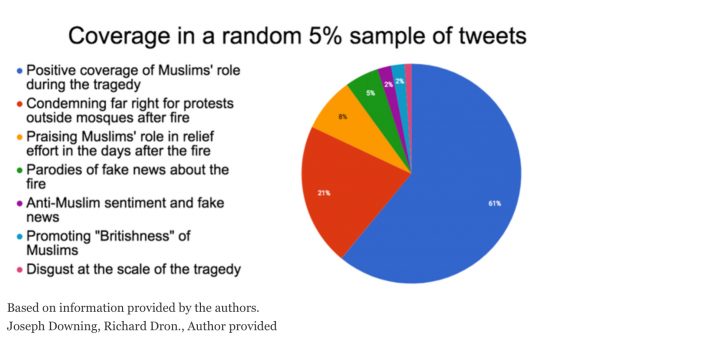

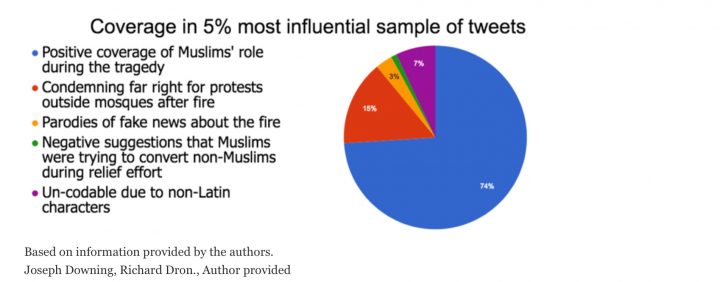

We wanted to see how much the fake news stories about the Grenfell fire being a terror attack actually influenced the debate online. So, we sampled the top 5% of tweets by influence – that is, how widely the tweet was spread – and analysed them on discovertext. We then compared this with a random 5% sample of tweets.

Once ranked by influence, the conspiracy theories all but disappeared from the debate. Instead, the most influential tweets were those about how helpful the Muslim population was, both during and after the fire. A full 74% of the most influential tweets spread messages about how Muslims, awake to close their Ramadan fasts, played a crucial role in spreading awareness of the fire and evacuating residents from the building.

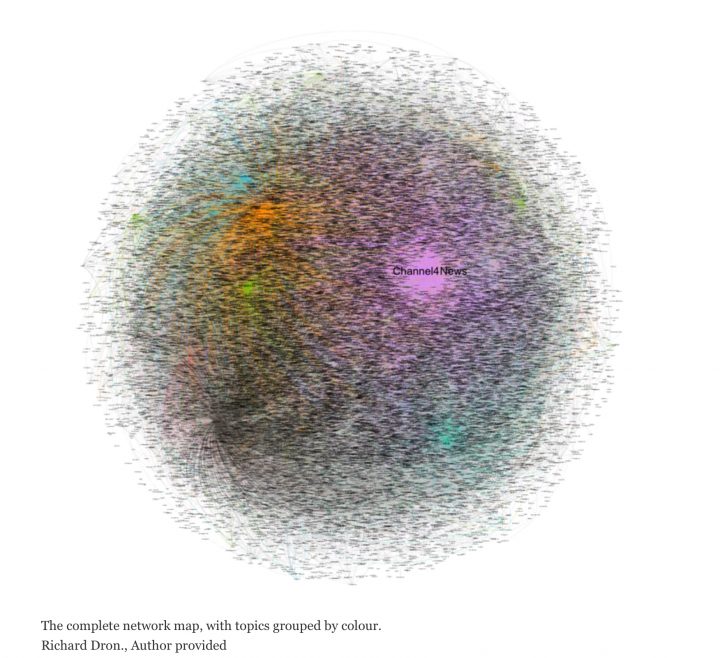

discovertext also allowed us to export the data, to generate comprehensive maps of the social network. The complete overview was made up of 812 intersecting networks; the boundaries are blurred, as messages pass between the different topics of discussion surrounding the fire – grouped by colour in the graphic.

Fighting fake news

We found we could examine not just how individual messages were spread, but also how they were refuted and contested. For example, one story concocted by fake news and conspiracy site InfoWars aggregated comments and tweets to claim that “Muslims celebrate London tower fire”. The story was shared 730 times.

But in the “post truth” era of Trump and Brexit, we were also interested to know how misleading information was challenged on social media. Grenfell was completely unlike the 2016 US presidential race – where fake news was widely spread and believed by users. Instead, misinformation was refuted by users, who shared stories from mainstream media to highlight the positive contributions of Muslims in the wake of the fire.

This graph shows how the InfoWars story spread, but also how it was challenged by users tweeting back articles from The Daily Mail, The Express, The Independent and The Telegraph, which pointed out how the local Muslim community helped at the height of the unfolding disaster.

![]() Clearly, fake news is not innately persuasive in all contexts – instead, it can trigger far more nuanced and complex processes on the social media platforms where it is spread. At a time when news coverage relating to Muslims is dominated by concerns about terrorism, Grenfell is a rare instance where people looked past religious and ethnic differences, to recognise the humanitarian contributions of this community, amid tragedy and disaster.

Clearly, fake news is not innately persuasive in all contexts – instead, it can trigger far more nuanced and complex processes on the social media platforms where it is spread. At a time when news coverage relating to Muslims is dominated by concerns about terrorism, Grenfell is a rare instance where people looked past religious and ethnic differences, to recognise the humanitarian contributions of this community, amid tragedy and disaster.

Joseph Downing, Marie Curie Fellow, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) and Richard Dron, Lecturer in Digital Enterprise & Innovation, University of Salford

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.