by Jhon Sánchez

Last year, Leland Cheuk, one of the editors of Newfound, wrote to me accepting one my short stories for publication. My story is dedicated to the New York Mills Art Cultural Center where I was an artist in residence in 2014. There, Leland was also an artist in residence in 2011. It was merely a beautiful coincidence. I was curious about my editor: I checked his website, read some of his interviews and I saw his picture. Leland lives in Brooklyn so do I. Another coincidence, I thought. Then, after I read “Letters from Dinosaurs,” his latest book I concluded with certainty, ‘this guy has a lot more in common with me than I thought.’ It was beyond my short story; it was beyond his experience at the NYM Cultural Center. Maybe, it is his keen observations and his characters in odd painful, situations that resembles my life. Sometimes, I feel that the opening story, “A Letter from a Dinosaur,” is signed by my own brother to one of his children, or even worse I’m both the writer and the recipient. Leland, thank you for putting together this collection, and let me tell, you sometimes in the subway I looked around for you and I have probably seen you more than once in all of us.

- Tell us about your transition from business graduate at Berkeley to a fiction writer?

Like a lot of young people, I didn’t have the courage to follow my heart and choose to pursue fiction writing 100%. My parents encouraged me to take a safer path, which I did, and honestly, I don’t regret it. I was able to make a living and draw from the business world frequently in my writing.

- The first story, A Letter from a Dinosaur, is indeed a letter addressed to you. Why did you choose your name to address the letter to yourself?

Oh, I was just having fun. I often throw my name into my work, much like Martin Amis and others have done in theirs, just to make the reader picture a version of the author that isn’t real. Some readers might think it’s distracting, but I, as a reader, enjoy it when it’s clear the author is enjoying themselves. So much of literary fiction is so serious and grim. It’s okay to have some fun. We’re making up stories, not atom bombs.

- I think the book covers topics of intergenerational conflicts. Do you think immigrant families have more conflict among themselves since they have to deal with the problems of biculturalism and a bilingual environment?

Well, I only know the family I have. There’s probably more open conflict in immigrant families because the different generations need to work a little harder to find shared values because of the cultural and language differences on top of the generational ones. One of the themes I often come back to is a second-generation American young person wanting the first-generation parent to say “I’m proud of you.” But in Chinese, for instance, there is no perfectly equivalent way to express that sentiment. To a second-generation American it seems like such a small thing to ask, but the differences between languages doesn’t allow for it.

- At least two of the stories deal with the viewpoint of a person who is near a perpetrator of a crime. I found this an unusual angle. We usually see the perspective of the perpetrator or the victim. We don’t enter into the intimate social circle of the perpetrator and the long lasting emotional effects on those people, the sense of guilt, or the inability to return to a ‘normal life’. Why did you decide to talk about that?

Complicity is a theme that I’ve been exploring. To what degree are our actions or non-actions indirectly or even directly responsible for a crime? If you work for a corporation that sullies the environment and its actions end up literally killing people, aren’t you complicit? If you choose to work for that company, aren’t you, in essence, aiding and abetting a criminal? The last story in the collection “Pyramid Schemes” deals with that idea directly. I was inspired by the suicide of Bernie Madoff’s son, who, by most accounts, didn’t actually know anything about Madoff’s massive pyramid scheme. In the story, I imagine a young person who is told by his father about the family business’s Ponzi scheme, and all the son really wants to do is fall in love and go to college and not have to deal with his father’s crime—which to me is totally understandable. What I’ve been trying to get at with these stories is: it takes courage not to be complicit.

- I’d like you to talk about the story, “First-Person Shooter,” because it deals with the problem of mass shootings in the USA. How did you come up with the idea for the story? After reading the story, I feel we are all unintended victims of the mass shootings in the USA. How can we cope with that? What can we do?

What I’ve been finding out lately is that the stories that I feel like I’ve worked on too long often come back to be relevant. I wrote the story after the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007. Sadly, stories about mass shootings aren’t going away anytime soon. Like many people, I feel pretty helpless. So many gun owners feel that giving any ground on the issue means the government will soon be confiscating all guns big, small, and ever made. I find that you can’t even engage these people on the premise that mass shootings are a problem or that their gun ownership is recreational. Immediately, they equate a school shooting to the misfortune of a car accident. “What are we going to do, ban cars?” When you can’t even agree on the premise or presence of an issue, how can you even hope to solve it? I’d even go as far as to say that if you own an AR-15 and are not willing to imagine any restriction on any level of your own gun ownership whether they be bump stocks or whatever, you are complicit. What it really comes down to is: thousands of people are being killed each year in the U.S. because of the recreational preferences of the few.

- Some of your stories deal with the topic of separation, fathers who had left their family, children who have separated from their parents, classmates whose destiny pulls them apart. Why is this topic important to you?

I come from a pretty broken family so that’s where I find my emotional impetus to write. Every writer has a different emotional impetus. For many writers, that impetus is family, friendships, and/or romantic relationships. Luckily just about everyone can relate to them.

- Since family relations are important in your narrative, can you tell us how your own family has fed your creative writing process? Can we see some of your relatives reflected in the stories?

The family dynamics in the story collection are less directly autobiographical than the ones in my novel. A good example is: I have a younger brother who I feel very close to. Siblings don’t appear in any of the stories. In the collection, I probably started with situations I directly experienced or ones where I knew somebody who went through something similar. For example, in “Funeral by the Arcade,” the funeral in the story is based on my wife’s grandfather’s funeral, which I attended and felt baffled by all the Chinese and Buddhist rituals. In “League of Losers,” I’ve been in a very serious fantasy baseball league for years and the email threads are absurd.

- You also have a sci-fi story called, 1776. The title of the story is ironic since it refers to Independence Day in a world where the protagonist, Jerry says, “ I am an American.” One of the characters in the story replies, “What does that even mean anymore?” So, let me ask you, “What does it mean to be an American, now?”

I’m in Scotland for a residency right now, and I feel very American when I’m overseas. It means you have a certain set of cultural references. It means you likely have a strong opinion on Trump and school shootings and the like, and depending on your opinions, you might feel ashamed of what the leaders of our country stand for right now. I think we’re continually discovering that being an American means different things to different Americans. For some Americans, when they picture what it means to be an American, you and I (both people of color) aren’t in that picture.

- I’m curious about Asian American literature. What are the commonalities between Latino-American and Asian American literature? How do they differ?

As a reader, I try as much as possible to evaluate every book on its own, without the hyphenated categories. This is a pretty good time for literature by people of color. It seems to be better than it was. I think if you read a lot of what’s been put out just in the last few years, you’ll find an enormous range of stories, themes, and aesthetics. For example, what do the work of, say, Jenny Zhang, Celeste Ng, and Karan Mahajan really have in common? Or Hector Tobar and Cristina Henriquez? I would argue not that much. They all deserve to be evaluated on the merits of their work alone and not their categories.

- How did you decide what stories to include in this collection? Did you exclude any stories from it? How did you decide on the order of the stories?

I probably took out 2-3 older stories because I just didn’t feel confident about them. All the published stories had to go in, of course. I tried to alternate shorter stories with longer ones. And then I wanted the last story to have a last line that would resonate not just for the story, but also for the collection as a whole. The last word in the collection is “end.” That’s literal and intentional!

- You also have a well-regarded novel, “The Misadventures of Sulliver Pong,” that I started reading. Do these stories relate to the novel? Do you touch on similar themes? Or on the contrary, do you think the go in different directions?

The novel is a black comedy about a very dysfunctional family, the patriarch of which lords over this border town in the Southwest as a mayor with a cult of personality. The son ends up running for office against his father and it doesn’t go well for either of them, or the town for that matter. I tell people that I’m most proud of the fact that the book came out in 2015, before Trump. A writer is always tickled when he/she/they predict the future. Some of the themes are similar, but the execution is different. It blends a lot of different genres into an unusual (at least, I think) whole. It could be called an American novel, family novel, a political novel, a comedy, a satire, a farce, an expat novel, a historical novel, and even a speculative one. It’s been translated into Chinese and is coming out in China later this year. I tried my best and I hope you like it!

- As an editor, do you have any recommendations for writers of short stories? What are you looking for when you read a short story?

The first page is critical. Set up an original premise on that first page. On the first line, there has to be something really unique going on in the voice. It’s almost an automatic rejection if the first line is something like: “So-and-so opened his eyes and checked his alarm clock.” I can’t believe how many stories start with the main character waking up in the morning.

- You were diagnosed with bone marrow cancer after finishing your MFA program. Can you tell us how this diagnosis impacted your creative career? Do you plan on writing a memoir down the road? Or do you prefer fiction?

I’ve toyed with the idea of a memoir. I have a few essays about cancer, including one that’ll be in an anthology in 2019 with authors I admire such as Ann Patchett, Laura van den Berg, Rumaan Alam, and Mat Johnson. I’m not sure I’ll pursue a memoir. I’m not sure there’s enough of a story there. I got cancer and I was very lucky to have the best care possible at the best hospital and I’m healthy now. So many cancer patients have had it much, much worse. It’s terrible to say, but the best cancer memoirs—and there have been several beautiful ones in the past few years—are the ones where the patient doesn’t survive. That said, I’m working on a number of short fictions that contemplate mortality, and leaving one’s mark, and all the other lives one could have led if one had more than just this one, very short lifetime.

- I heard that you haven’t taken the subway in a while, waiting to strengthen your immune system. Leland, remember we’re going to see each other on a Brooklyn bound train one of these days. Maybe I’ll be rereading your book, then.

(Haha, I am okay to take the subway now. Boy, it got a lot worse while I was sick!)

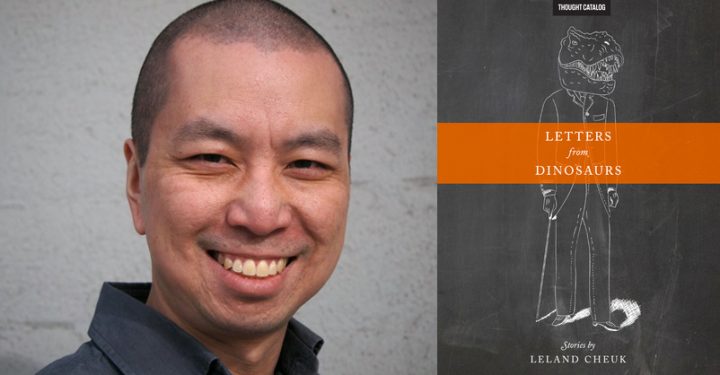

Leland Cheuk: A MacDowell Colony and Hawthornden Castle Fellow, Leland Cheuk is the author of the story collection LETTERS FROM DINOSAURS (2016) and the novel THE MISADVENTURES OF SULLIVER PONG (2015. Cheuk’s work has been covered in VICE, The Millions, The Rumpus, and Asian American Writers Workshop, and has appeared in or is forthcoming in publications such as Salon, Catapult, Joyland Magazine, Electric Literature, The Rumpus, Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, [PANK] Magazine, among other outlets. He teaches at the Sarah Lawrence College Writing Institute. He is the fiction editor at Newfound Journal and the founder of the indie press 7.13 Books. He lives in Brooklyn. You can follow him on Twitter @lcheuk and at lelandcheuk.com.

Jhon Sánchez: A native of Colombia, Mr. Sánchez immigrated to the United States seeking political asylum. Currently, a New York attorney, he’s a JD/MFA graduate. His work has been nominated for The Best of the Net 2016 and for a Pushcart Prize in 2015 and 2016. He was also awarded the Newnan Art Rez Program for summer of 2017. More of Mr. Sanchez’s work can be found at Caveat Lector, Breakwater Review, Newfound, Gemini Magazine, 34thParallel, Foliate Oak Literary Journal, Swamp Ape Review, Sand Hill Review, Midway Journal and more recently in Midway Journal Volume 11 Issue 4