By Skanda Kadirgamar

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s 2018 State of the City address, held on Feb. 13 at Brooklyn’s renowned King’s Theater, was premised on a particularly bold claim. The words “Mayor Bill de Blasio Making New York America’s Fairest Big City” were emblazoned on the marquee so that attendees, passersby and the scores of protesters who had been forced to the other side of Flatbush Avenue couldn’t miss them.

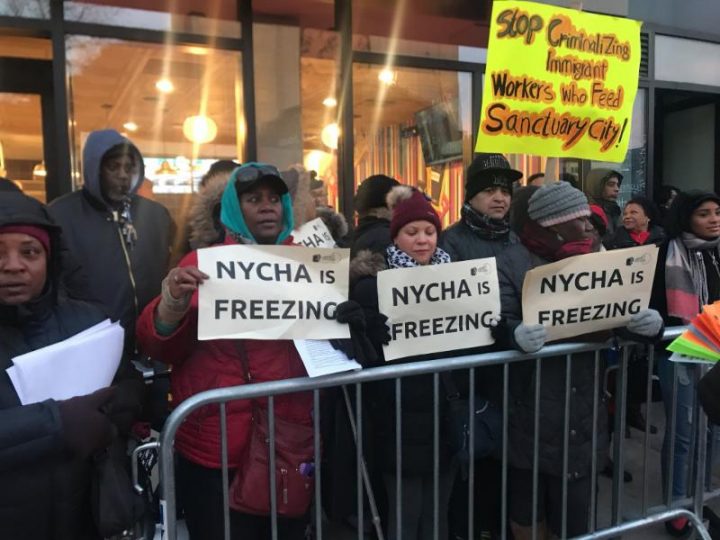

Yet, de Blasio has advocated for the privatization of public housing and has the support of major real estate interests. It’s no surprise then that his “tale of two cities” rhetoric leaves public housing tenants cold, in some sense literally. This winter, more than 320,000 New York City Housing Authority, or NYCHA, residents lost either their heat or hot water, exemplifying decades of neglect. In response, some are rallying with the grassroots organization Community Voices Heard, or CVH. They are pushing a platform that demands the mayor make good on his progressive rhetoric and take bold measures to abolish their hazardous living conditions.

Protesters from CVH began assembling in front of the theater at around 5 p.m. to demand that the mayor fully fund repairs in public housing. Within minutes of their arrival, police ordered the demonstrators — who came from a number of other groups, including Equality for Flatbush, the Street Vendor Project and Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence — to the opposite side of the street, where they were blocked from view by NYPD vans. But the group remained steadfast due to the high stakes of their campaign.

Aside from having to deal with failing boilers, which are at least 50 years old, residents are also fed up with lingering toxic mold and lead paint. According one lawyer in a class action suit that resulted in a $57 million settlement from the NYCHA, the problems with lead paint have been acknowledged since the 1960s. Lapses like these are the product of decades of privatization and the whittling away at funding for public housing.

In February 2017, CVH responded to this human catastrophe with a rally on the steps of City Hall that was dubbed “NYCHA’s Making Me Sick.” However, their demands — calling for the city budget to be used to address public health and housing crises affecting low-income black and brown communities — went unheard. Towards the end of last year, New York City officials began calling for the resignation of NYCHA Chief Executive Shola Olatoye for incorrectly stating that the housing authority had been properly conducting lead paint inspections.

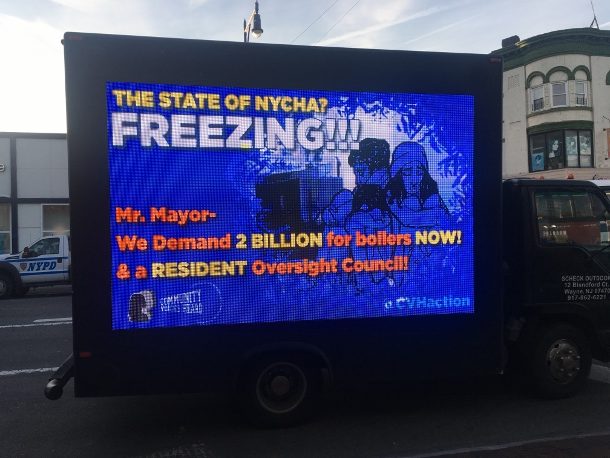

Drawing on momentum provided by its member-leaders — NYCHA residents who are now trained organizers — Community Voices Heard has been pushing a model for public housing based on local finance and community control. This year, they want the mayor’s office to commit $2 billion of the city’s nearly $89 billion budget to overhaul infrastructure. Last year, CVH prevailed upon the mayor to allocate $1 billion annually to repairs and improving conditions. Since de Blasio did not make that commitment, they’ve raised this year’s request accordingly.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development is typically the mainstay of financial support for public housing. With the Trump budget threatening to take $466 million away from NYCHA, however, local funding has become even more crucial. For CVH lead organizer Gabriel Strachota, doing something unprecedented — like directing substantial amounts of city money to public housing — would demonstrate that de Blasio is ready to “put his money where his mouth is when it comes to being a Progressive Democrat.” Strachota argues that while de Blasio was not the first mayor to support a privatization agenda in New York, he has contributed to growing the various crises in NYCHA by endorsing the idea that there is no alternative to public-private partnerships.

Beyond providing the necessary funding, CVH also wants the city to be truly accountable to residents. This means recognizing and elevating their power as stakeholders in their own homes. Thus, CVH has proposed the formation of a resident-led oversight board meant to combat negligence and cover-ups on the part of NYCHA. Comprised of the heads of tenants associations from NYCHA buildings throughout the city, this body would certify whether repairs are completed or not and would have access to the agency’s internal documents upon request.

A vehicle advertising the demands of Community Voices Heard for the mayor outside of his speech. (WNV/Skanda Kadirgamar)

This two-pronged attack on the city’s inaction — demanding local funding and giving residents their own watchdog group — is representative of CVH’s strategic model, which they call “power analysis.” As Strachota explains, their understanding of power is drawn from a definition Martin Luther King Jr. provided, when he said “power is the ability to achieve purpose.”

This approach revolves around the political clout that residents can generate themselves. Strachota said that both the growth and integrity of CVH’s campaigning relies upon the relationships between NYCHA residents. As he further explained, “one key source of power is through organized people, through the assemblage of relationships.” In the wake of the “bomb cyclone” in January, there are signs that their efforts may be having an impact, as members of City Council are beginning to call upon the mayor to increase funding for the NYCHA.

Building the power of tenants entails helping them organize in networks that can take collective action. There are many examples of this from the weeks leading up to the State of the City protest. On January 18, residents from each of the five boroughs met at CUNY’s Murphy Institute to discuss tactics for pressuring the administration that ranged from gathering petitions to organizing marches to filing class action suits. On February 2, CVH helped further escalate pressure by coordinating a mass call-in to de Blasio’s office. Over 800 people flooded the mayor’s phone that day.

To ensure that collective action continues, CVH trains its members to organize their communities. This involves CVH members recruiting leaders in their buildings, workplaces, schools and families who are influential enough to consistently bring people into the organizing process, which include attending actions and meetings. Cultivating that organic leadership prevents campaign work from turning into a series of one-off actions that allow political energy and focus to dissipate in their aftermath.

CVH develops its relationships with these organic leaders and aims to further develop their effectiveness as organizers by using a method that was central to the work of Fred Ross, Cesar Chavez and Delores Huerta. “The first thing we do is that we build a relationship with them,” Strachota said. “We sit down with them and have a one-to-one meeting, but we’re not talking about policy. We’re talking about who a person is and what’s happened to them to make them that way.”

Talking to these prospective organizers about the struggles they face is crucial to their understanding of the roles they play in the campaign. That self reflection is also key to their understanding of power. Afterwards, these individuals often are asked to hold a house meeting, to gather people they know and try to solicit active support for the campaign from them. According to Strachota, meetings like these were the foundation of both the United Farm Workers and the Community Service Organization, which for decades has been emphasizing to unions the strategic importance of building collective power through face-to-face gatherings.

Rose Fernandes and her son Giancarlo are among the residents who have joined the struggle and have been animated by the force of this organizing process. Rose, having faced too many winters without water or heat, was slow to join initially. The weathering effect of neglect and isolation were the source of her reticence. “At one point, I had kind of been in this sleep state,” she said. “I didn’t know what to do, who to talk to. I didn’t think anybody would listen.” After organizing for about a year and seeing more people push back against the city and NYCHA management, she said she was thrilled and that CVH helped her find her voice.

“One of the things that’s hardest to organize against is the sense of hopelessness and suspicion that exists among residents,” said Giancarlo, who was responsible for bringing his mother into the organizing process. “My mom thought it was a cult or someone trying to get money out of us.” Sentiment like this is reinforced by predatory behavior and retaliation from the people who run the housing authority. At one point, a NYCHA manager refused to perform needed maintenance in their apartment in an attempt to extort money. According to Giancarlo, hostility like this, in addition to the threat of eviction, is the norm in public housing and makes residents fearful of taking action.

Having the opportunity to push back against such oppression is what motivates him as an organizer. That, in turn, has reframed how he views the building he calls home, as well as the power dynamics that shape it. “Most of the time what I had heard about living in NYCHA was ‘keep your head down, get a good job and leave,’” Giancarlo explained. “But the truth is that it’s very difficult because as your salary increases so does your rent.” Ensuring that residents have power in public housing is now a goal for him. “CVH offered me a path that was not any of the dominant narrative storylines I was being fed about trying to get out. I could organize and be a part of the change I wanted to see in NYCHA.”

The work of organizers like Rose and Giancarlo Fernandes will become even more crucial now that the Trump budget has been passed, which comes with a rent hike to as much as 35 percent of NYCHA residents’ gross income. The coming years will be rough. However, tenants are discovering their agency and many are considering responding to Trump’s onslaught and de Blasio’s intransigence with a rent strike. The question remains, however, whether the networks they’ve built have generated the power they need to pull off such an ambitious action in this particular moment.