By George Lakey February 1, 2018

Once again I rang the bell at the brick row house in East Boston where Gene Sharp lived. When he opened the door I said proudly, “Today I drove here instead of taking the T.”

“You drove?” he said in mock horror. “Man, are you trying to get yourself killed? Haven’t you heard about Boston drivers? They show no mercy, especially toward Philadelphians!”

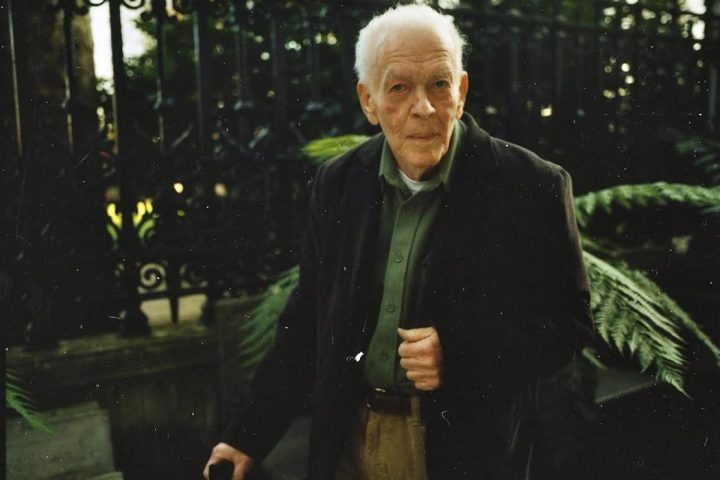

That was the Gene Sharp I knew, always loving to find a joke in the moment. So, I was sad to hear the news that he passed away on Sunday at the age of 90.

When I had him speak at Swarthmore College he put on his distinguished scholar persona, adding the English accent he’d learned while studying at Oxford. When one of my students asked a particularly penetrating question, Gene, at the time associated with Harvard, peered over his glasses and said, “Hmm, it appears to be true: Swarthmore students really are brighter than Harvard students.”

Even though he charmed my students, he also relished the role of contrarian. Not easy, if your life mission is to bring into the mainstream an area of study previously on the intellectual margin.

I was 21 years old when I met him. I was studying sociology at the University of Oslo. One of my teachers there who knew of my interest in the peace movement said that I might like to meet someone at the university who was researching Norwegian nonviolent resistance to the German Nazi occupation in World War II.

I dropped by his office and found a 30-year-old in jeans and sneakers with a quick smile. We both welcomed the chance to speak English, although his Norwegian was much better than mine. My eyes widened when he told me he was not only digging into stories of Norwegian resistance, but was going to conferences where he interviewed Africans in anti-colonial struggles who told him of nonviolent tactics being used there, sometimes alongside armed struggle.

At first I couldn’t make sense of it. Gene had been to prison as a conscientious objector and then became secretary to A.J. Muste, who Time magazine called “America’s number one pacifist.” I’d become a pacifist only recently after a fierce internal struggle, given my family’s pro-military beliefs. To me, the choice between violence and nonviolence was a choice of moral conviction. What happens to moral choice when we research violent and nonviolent methods as if they are alternative means to an end?

In dialogue with Gene over time I realized he was not closing the door on ethics. Instead, he saw much more promise through opening the door of practical advantages of nonviolent struggle. He and I wanted the same thing: maximum attraction to nonviolent struggle to win justice.

Gene also told me stories of his own disappointment, when pacifist intellectuals he knew who could have developed pragmatic strategies for nonviolent struggle chose not to, falling back on their ethical choice as their default. As an eager-beaver student, already set on getting a master’s in sociology, I sympathized with Gene’s eagerness to take on the tough questions on their own terms rather than rely on a default answer. From there, it wasn’t hard for Gene to convince me that I should write my own thesis on nonviolent struggle.

We stayed in touch after I returned to the United States, and — with his encouragement — I persuaded the University of Pennsylvania’s sociology department to allow me to write that thesis. In it, I proposed that there is not just one way that nonviolent campaigners win, when they do, but instead there are three different mechanisms through which success can come. Gene then adopted the mechanisms for his own work.

The lonely researcher

It’s difficult to understand in 2018 — when so many people around the world are researching and writing with sophistication about nonviolent struggle — how lonely Gene’s path was in the early years. When I met him in 1959, Gene was the only person in the world doing full-time research in nonviolent struggle.

True, peace and conflict research was happening at the same time, with a scholarly journal around Kenneth and Elise Boulding, based at the University of Michigan. In Oslo, I helped Johan Galtung on his first peace research project. The emerging field’s focus was on conflict resolution. Gene’s, however, was on conflict-waging.

I saw this emphasis coming from Gene’s being a warrior. His passion was to map a territory where fighters could take on their biggest opponents and win, nonviolently. Winning that way, he believed, could make a big difference. Whatever the win/win conflict resolution people might offer, Gene believed there are some struggles where the result needs to be a loss for one side: slaveholders needed to lose their slaves; fascists needed to lose their secret police.

His disposition to be a nonviolent warrior at a time when so many non-warriors were looking for conflict resolution, and warriors looking for a way to apply violence, made him a lonely scholar. To my eyes his perseverance made him a hero.

A technology with multiple applications

Thanks to Gene, we can think of nonviolent action as a social invention that has multiple applications. Nonviolent change, from neighborhood to international levels, is probably best known. Most people also understand Nonviolent defense struggles, which includes defending the environment, indigenous rights and other human rights. Less well known is defense of communities against occupation and annexation. Then there are the applications still needing further development, such as defending against terrorist threat — something we made some progress on at Swarthmore. Finally, there are the applications waiting to be developed. Gene told me he wished people would tackle the research needed to begin to erect nonviolent defense against genocide.

One application that Gene spent years tackling proved to be particularly controversial. In 1964, Gene invited me to present a paper at the first international conference on civilian-based defense, or CBD, at Oxford University. The fear of nuclear war had triggered a growth of disarmament movements in multiple countries, but they had the all-too-familiar problem: no real alternative to military defense.

If you’re looking to defend your people from attack and occupation by a hostile power, consider the advantages of building a nonviolent defense system, Gene suggested. We learned at the conference from one of the foremost military strategists of the day, Sir B. H. Liddell Hart, that he had already advised exactly that to the Danish government shortly after World War II.

In Europe, seeing the idea of CBD taken seriously alarmed a number of radicals. Anarchists were joined by others who had a dim view of governmental behavior and couldn’t imagine how there could be liberating outcomes for nonviolence once the state got hold of it.

While I joined the anarchists in being wary of the state, Gene won me over with a set of arguments including his analysis of the dynamic impact of the means of conflict that we use. Choosing military defense, he said, has a centralizing impact and heightens authoritarian relations. Nonviolent defense is the opposite. The work so far done on CBD points to the most promising nonviolent defense strategies having a decentralizing impact, empowering the grassroots of society.

If he’s right, then it makes sense for decentralists to support further development of CBD for countries — like the Nordic ones — that might consider trans-arming, the term we invented to get around the non-starter of disarmament. In my view, for countries like the United States, where the 1 percent rule and have a vested interest in opposing trans-armament, CBD might usefully be considered for inclusion in our vision — to be implemented when we push the 1 percent aside and make the major changes needed for a living revolution.

Seeing events with new eyes

Some years ago, high schoolers in Philadelphia banded together to form a city-wide schools reform movement, the Philadelphia Student Union. To inaugurate training they invited me in to lead workshops. One day I handed out newspapers I’d collected from the previous three weeks and asked them to look through them to find out what kinds of nonviolent action they found being used. I first asked them what they considered “nonviolent action” to be, weaving parts together into what amounted to Gene Sharp’s classical definition.

They dove into the newspapers and amazed themselves with the large number of tactics they found reported on at the local, national and international levels.

A Swarthmore College international student came into the nonviolent research seminar I was leading and told me she wanted to research cases but was regretful that her own country had no nonviolent experience of its own. I smiled and said, “We’ll see.” In a matter of weeks she was bringing cases to the seminar from her own country. By giving her new eyes to see with, Gene had given her back her own country’s history.

To me this is Gene’s most important single contribution. He defined nonviolent struggle in behavioral terms, so clearly that people are empowered. They can see what’s happening now and recover their legacy as well.

Gene’s own eyes sparkled with pleasure a few years back when my student Max Rennebohm and I showed him the Global Nonviolent Action Database, which, at the time, comprised over 500 cases compiled by Swarthmore students. Now there are over 1,100 cases, spanning nearly every country — including the doubting international student’s home country — giving inspiration and strategic hints to all who access it. The database, based on Gene’s conception of the field, is one of his living memorials. But I’ll miss him all the same.