By Maxine Lowy*

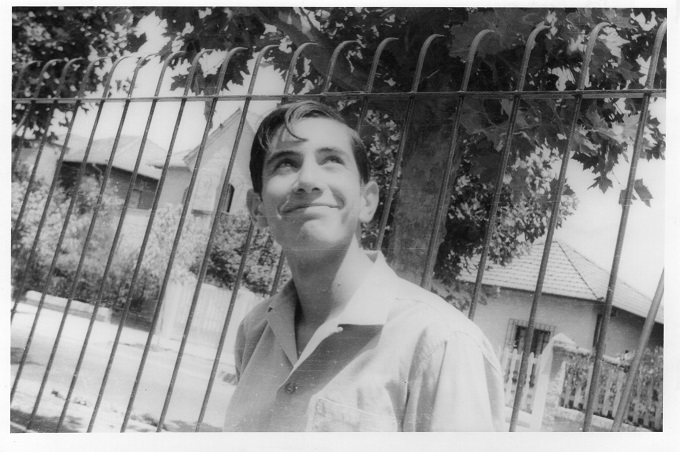

In the hours before New Year’s Eve 1975, sociology student and Socialist Party member Jaime Robotham was walking with his friend Claudio Thauby along Santiago’s

Providencia neighborhood, when agents of the repressive DINA police drove past, saw them, violently apprehended them and took them away. Their families were never to see them again, yet seven months later, two burned bodies were found across the Andes near Buenos Aires, Argentina, with Chilean identity cards nearby, one of which bore Jaime’s name.

This month marks 42 years since the discovery in July 1975 of those bodies in Pilar, a town near Buenos Aires, in the initial stage of a scheme jointly carried out by Argentina and Chilean military intelligence, which came to be known as Operation Colombo. Today Jaime’s family calls for an investigation of key elements that have never been clarified.

In 1975, when international condemnation of Chilean disregard for human dignity had isolated the country, and human rights defenders had gained greater understanding as to how the repression operated, the dictatorship headed by Augusto Pinochet devised a plan to disguise their practice of forced disappearance. But the plan turned out to be so inept that it ended up pointing directly to those who had thought up the ruse.

Operation Colombo capitalized on the presence of thousands of Chilean refugees in Argentina. Upon arriving Chileans were advised to pretend they were from the Argentine border city of Mendoza, because Argentine officials believed Chileans were terrorists. In fact, the year before, in June 1974, Jaime Robotham had been in Buenos Aires on a fundraising and reorganization mission for the proscribed Chilean Socialist Party, which had gone underground after the dictatorship outlawed political parties.

Operation Colombo also reinforced coordinated intelligence efforts between the Chilean and Argentine military. In September 1974, they had collaborated to assassinate former Army Commander-in-Chief Carlos Prats and his wife Sofia Cuthbert, in Buenos Aires’ Palermo district. Ten months later, such collaboration would be formalized in Operation Condor, the repressive military network uniting Southern Cone dictatorships.

On April 16, 1975 in a Buenos Aires parking garage on Sarmiento Street, a mutilated corpse was found, accompanied by a Chilean identification card, was founds. The ID card carried the name of David Silberman, a Chilean civil engineer who was last seen in October 1974 in the secret detention and torture center on Jose Domingo Cañas Street in Santiago. Then, on July 11, two burnt corpses were found in a car parked on Chile Street in the town of Pilar, outside Buenos Aires. Chilean identification cards with the names of Jaime Robotham and architect Luis Guendelman were found unscathed nearby. Robotham and Guendelman had been detained and subsequently missing since 1974. On July 19, the pattern was repeated with the discovery of another body, this time with an identification card allegedly belonging to Juan Carlos Perelman, a chemical engineer arrested in Santiago on February 2, 1975, and seen that month in Villa Grimaldi.

Meanwhile, on July 15, newspaper kiosks in Buenos Aires were flooded with a new publication – “Lea,” a magazine of a single edition – that listed the names of 60 Chileans supposedly killed in an internal purge of leftwing movements. And on July 24, this time in Brazil, another new single-issue publication appeared in newsstands kiosks – “Novo O Día”- listing the names of 50 more Chileans allegedly “killed in clashes with Argentine forces near Salta.” Together, the two lists contained 119 names which numerous articles widely covered in Chile and abroad claimed to be those of Chileans killed in internal purges in Argentina.

In 2005 Judge Victor Montiglio, of the Santiago Court of Appeals, indicted Augusto Pinochet for Operation Colombo. In 2008 the same judge indicted 98 commanders and former agents of the DINA secret police on for 60 victims listed among the 119 people. The court probe proved the circumstances of their arrests: all had been kidnapped and had been held in various clandestine detention centers in Chile. These included 38 Londres Street, José Domingo Cañas, Iran, and Villa Grimaldi, known by their military nomenclature of Yucatan, Ollague, Tacora, and Terranova, respectively. The judge proved that none of the 119 missing could have been in Argentina at the time they were purported to have died. He also established the participation of the DINA agents who had drawn up the lists of names and falsified identification cards.

But, the identity theft and the discovery of the four bodies, that comprised the initial stage of Operation Colombo, have never been investigated.

The Silberman, Robotham, Guendelman and Perelman families had been searching for their respective members, and now were forced to travel to Buenos Aires to face the gruesome visage in the morgue of burnt bodies. Despite the disfigured conditions, family members confirmed that the bodies did not correspond to their purported identified. This confirmation was supported by self-incriminating evidence, including misspelled surnames, forged signatures, and outdated photographs on the identification cards.

For example, in February 1975, detectives went to the Robotham home in Santiago, requesting a photograph of Jaime. (Surviving prisoners later testified that in those days they saw Jaime and his friend Claudio Thauby in the Villa Grimaldi detention camp.) Four months later, the same photo appeared glued to an identification card with Jaime’s name, found next to one of the bodies discovered in Pilar, Argentina.

A letter dated September 16, 2015 from the Buenos Aires Public Ministry Prosecutor’s office indicates “bullet wound to the head” as cause of death of the two bodies accompanied by the identity cards with the misspelled surnames of Jaime Robotham and Luis Guendelman. The letter surfaced in Argentina as part of the case against military Junta leader Jorge Rafael Videla and others for “illegal deprivation of liberty.” The letter also states that: “The deceased… were buried as NN [No Name] in the Pilar Municipal Cemetery on July 23, 1975 by police order, and were placed in section 13, grave n. 50, but subsequently transferred to the indigent burial grounds.” Eleven days after the discovery of the bodies, they were buried without an investigation.

Yet, it appears some information does exist, including fingerprints of at least one of the victims found inside the car in Pilar, according to Argentine officials.

Jorge Robotham, Jaime’s older brother, calls on Argentine judicial officials to investigate the identities of the four bodies and the circumstances surrounding their deaths. Reflecting about the episode today, in an interview with this author held in June, he said, “The trauma of having to face the horrendous sight of a burnt corpse is not conducive to drawing precise conclusions, at least not in regards to the body associated with my brother Jaime’s name.” He thinks an Argentine court investigation may uncover greater information about how the scheme was organized.

Simon Guendelman is the brother of Luis Guendelman, who was abducted on September 4, 1974 in Santiago. Guendelman remarked to this author that when he learned his mother and sister-in-law had discounted any possibility that a body found in Pilar could pertain to Luis, he immediately wondered, “If it’s not Lucho, then who is it? What other family, like ours, is searching for a loved one?”

That’s what Jorge Robotham hopes to find out. Jaime was eight years younger than Jorge. “When he was a little kid, I wasn’t interested in what he was up to,” he laughs. More than four decades later, when that “little kid” would have been 66 years old, the pursuit of justice for his brother comprises the driving force of his life.

*Maxine Lowy is a journalist and translator who lives and works in Santiago, Chile. In 2016 she published the book “Memoria Latente” (LOM Ediciones).