Does globalisation promote development? If you scratch beneath the surface, the answer of OECD researchers to this crucial question in times of financial collapse and its atrocious consequences for the vulnerable sections of people around the world is: globalisation helps the rich get richer and the poor poorer.

“The poorest country in 2011 was poorer than the poorest country in 1980. And much of humankind continues to live on less than USD 1 a day,” says a new study by the 34-nation bloc of mainly industrialised and some emerging countries, which devotes some 20 out of 157 pages to analyse whether globalisation promotes development, and sums up:

“Globalisation first promoted the development of industrialised countries, then, in the past 20 years, that of emerging countries. While some developing countries are following in their footsteps, others have become marginalised or weakened by opening to international markets. Extreme global poverty has diminished, but is still ingrained in certain regions. In many countries, inequalities have deepened. Globalisation can only promote development if certain political conditions are combined.”

The study titled ‘Economic Globalisation: Origins and Consequences‘ is part of a series of ‘OECD Insights’ commissioned by the Public Affairs and Communications Directorate of Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. It is authored by Jean-Yves Huwart and Loïc Verdier. They tell two stories to underline the gist of their findings highlighting the two faces of globalisation:

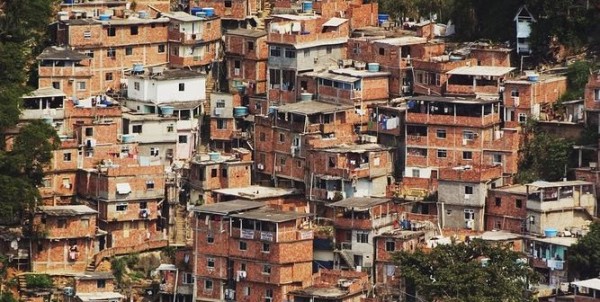

“Twelve years ago, professional manicurist Edmila Silva and her partner Neno left their rural province in northeast Brazil to settle in the suburbs of São Paulo. Thanks to two decades of national economic stability and constant growth, the region experienced a spectacular drop in unemployment over the past 10 years.

This success is partly due to the Brazilian economy’s integration into international markets: in 20 years, the share of international trade in Brazil’s growth has doubled. This led to a range of new jobs and to many families experiencing higher purchasing power. ‘We have many, many more opportunities than before’, says the young manicurist. Today, she drives a small new car, owns a mobile phone and has health insurance. Two years ago, she opened a bank account and took out a consumer loan. She is thinking of going back to school to become a nurse or chiropodist. ‘I am very independent now’, she says. ‘I have more self-confidence. The future is smiling on us.’

At the same moment, in Sikasso, 250 km from Mali’s capital Bamako, farmer Yacouba Traoré is complaining about the Malian textile development company – the obligatory intermediary between Malian cotton producers and international markets. ‘Last year, they paid me 210 CFA francs per kilo of cotton’, said this father of six. ‘This year, only 150 CFA francs.’

Despite its high quality, Malian cotton can’t compete with producers from the north, who supply vast quantities and enjoy high living standards thanks to subsidies. To make things worse, food prices soared this year: imported rice, which is less expensive than local rice, has shot up from 250 to 350 CFA francs in just a few months. ‘I earn less and less even though the cost of living is higher and higher! Barring a miracle, I’m sure I won’t be able to send my two youngest children to school next year’.”

Two faces of globalisation

These two faces of globalisation show on the one hand an opening to trade that brings progress and development. On the other, weakened populations are trapped in a spiral of poverty. “There are two ways to understand the impact of globalisation on development: study the overall situation of countries and study the development of populations inside the countries,” the researchers explain.

But they add rather frankly: “Certainly, a country’s development level plays a role in the development of its population, but this link isn’t automatic. Thanks to globalisation, developing countries are indeed catching up on affluent countries – but the gulf between the richest and the poorest fringes of the world population seems to have widened.”

And yet, says the study, in the last 20 years, rapid globalisation has occurred alongside a worldwide decrease in extreme poverty. Since 1990, the number of people surviving on under USD 1 a day has dropped by 25 percent – that’s 500 million people. From 1990 to today, the share of the world population living in extreme poverty has dropped from 31 percent to 19 percent, it adds.

But these numbers owe a lot to China’s good results. In the past 15 years, China’s per capita income grew faster than in most developing countries. In 1981, 835 million Chinese lived on less than USD 1.25 a day, compared with “only” 208 million today. While the “world’s factory” is going at full capacity, says the study, “it does not necessarily make its neighbours very happy . . . (because) not only is poverty not decreasing in other countries and regions around the world, it’s sometimes increasing.”

More poor people

A case in point is southern Asia, where the number of people living in poverty has risen despite the high growth rates experienced by many of the region’s countries. India’s indigent population, for example, has soared to 36 million in the same 15-year period. As a share of total population, though, poverty has actually decreased from 58 percent to 42 percent. “But while millions of Indians now subsist on more than USD 1.25 a day, 75% still live on less than USD 2 a day,” avers the study.

Another case in point is sub-Saharan Africa, which is still lagging behind in terms of development. A full 50 percent of its population has been living in poverty for the past 30 years, notes the OECD study. What is more, two-thirds of the poorest people on earth live in Africa. “It wasn’t always this way. In 1970, 11 percent of the world’s poorest lived in Africa, compared with 76% in Asia. The ratio has completely reversed in under 30 years,” the researchers find.

They continue: “Some world regions have become poorer. Comparatively speaking, the poorest country in 2011 was poorer than the poorest country in 1980. And much of humankind continues to live on less than USD 1 a day.”

The study further admits that not all the developing countries have benefited from globalisation. Many countries have stagnated in the past 20 years. In 2006, GDP in 42 world countries did not exceed USD 875 per capita.

Among these were 34 countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Madagascar, the Republic of Guinea, Democratic Republic of the Congo), 4 in Latin America (Bolivia, Guyana, Honduras, Nicaragua) and 3 in Asia (Myanmar, Laos, Viet Nam – although the latter just joined the intermediate country classification in 2010). Among the 49 least advanced countries, according to the United Nations definition, were Bangladesh, Yemen and Haiti. [IDN-InDepthNews – April 22, 2013]

Image credit: bsr.london.edu