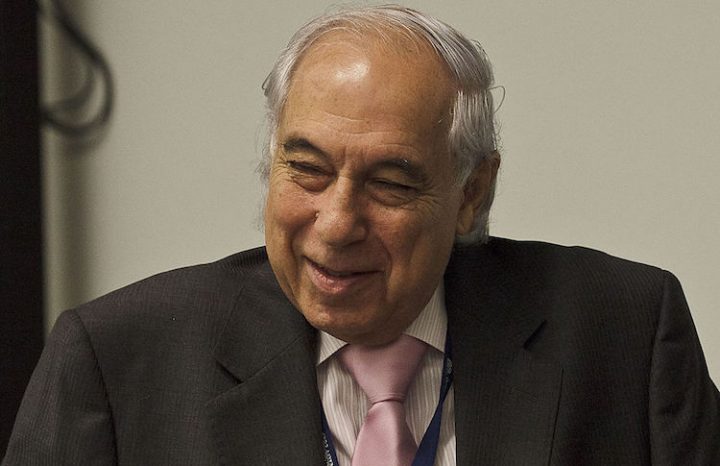

By Sergio Duarte, Ambassador, former High Representative of the UN for Disarmament Affairs*

The timely release of the draft Convention on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons by President Elayne Whyte-Gómez well in advance of the start of the second part of the negotiations will permit delegations from Member States and participating non-governmental organizations as well as interested institutions and individuals to study the text and come to the United Nations on June 15 fully prepared to contribute to the finalization of the Convention.

A first look at the draft brings to mind the importance of the humanitarian considerations that lie at the basis of the movement to achieve an international legal norm against nuclear weapons. The first five preambular paragraphs clearly recognize the catastrophic consequences and implications of any use of nuclear weapons and the suffering of victims of such use and of those affected by nuclear weapon tests and go on to reaffirm the rules applying to armed conflict.

Most importantly, the Preamble declares that any such use is contrary to the rules of international law, in particular the principles and rules of humanitarian law, which derive from established custom, from the principles of humanity and from the dictates of public conscience.

The subsequent preambular paragraphs express the determination of the States Parties to the Convention to contribute to the realization of the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and to act toward the achievement of further effective measures of nuclear disarmament in order to facilitate the elimination from national arsenals of nuclear weapons and the means of their delivery.

They also stress the existence of an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament, as contained in the unanimous ICJ Advisory Opinion of July 8 1996. The crucial importance of the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), of the Comprehensive Test-ban Treaty (CTBT) and of the instruments establishing nuclear-weapon-free zones toward the strengthening of the non-proliferation regime and realizing the objective of nuclear disarmament is duly reaffirmed.

These expressions make abudantly clear that the draft in no way aims at disrupting the existing non-proliferation regime or undermining its legal basis, but rather at its strengthening in order to realize longstanding objectives of the international community as a whole.

The first two operative paragraphs are clearly formulated and spell out the basic obligations to be undertaken by the Parties with regard to nuclear weapons as well as the steps to be followed in the fulfilment of such obligations. Prohibitions contained in Article 1. (a) to (g) encompass, among oter activities, the development, production, manufacture of nuclear weapons and other nuclear explosive devices as well as their posesssion and stockpiling. The transfer of such weapons or devices and their stationing, installation or deployment anywhere is likewise outlawed. Article 1.2.(a) reinforces the provisions of the CTBT by prohibiting any nuclear test explosion or any other nuclear explosion.

Drawing on the example set by the Chemical Weapons Convention each Party to this new Convention is required to submit a declaration on whether it has manufactured, possessed or otherwise acquired nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices after a certain date. This provision does not, however, require the destruction of the declared weapons or devices.

Article 3 deals with the obligation to accept safeguards to prevent diversion of nuclear energy from peaceful uses to nuclear weapons or other esxplosive devices, as provided for in the Annex of the Convention. It is important to ensure that the application of such safeguards is performed in full accordance with the Statutes of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

The interesting and innovative provisions contained in articles 4 and 5 seem to need further clarification. According to Article 4, States Party that have eliminated, prior to the entry into force of the Convention for it, nuclear weapons manufactured, possessed or otherwise acquired after that date undertake to cooperate with the IAEA for the purpose of verification of the completeness of its inventory of nuclear materials and installations.

This pressuposes that the process of elimination of nuclear weapons must precede the entry into force of the Convention for each State accepting that obligation. Such process, however, is not subject to independent verification.

Article 5 then becomes very relevant, since it deals with proposals for further effective measures of nuclear disarmament, including the verified and irreversible elimination of any remaining nuclear weapons programmes, especially through Protocols to be considered by the Parties to the Convention. States that become Parties to the Convention and which possess nuclear weapons manufactured or otherwise acquired before December 5, 2001 can avail themselves of the possibility of proposing further effective measures relating to their nuclear disarmament to be considered by the States Parties at their Meetings as provided for in Article 9 and adopted by the Convention.

In this way, the Convention remains permanently open to the inclusion of new Parties that decide to eliminate their own nuclear arsenals according to the provisions of the Convention and then accede to it at a time of their own choosing. Significant segments of public opinion in States that do not possess nuclear weapons themselves, but which have nuclear hosting or nuclear sharing arrangements with nuclear weapon States could be attracted to this possibility and help bring about changes in the current attitudes of their governments.

The remaining draft provisions are quite clear and should not raise much controversy. Article 6 is in line with the humanitarian inspiration of the Convention. Article 9 makes possibe for States not Party to attend the Meetings and Review Conferences as observers. Article 13 is innovative inasmuch as it fosters adherence to the Convention by calling upon on States party to “encourage” non-Parties to ratify, accept, approve or accede to it. Explicit mention is made in Article 19 to the fact that the Convention does not affect the rights and obligations of Parties to the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

The text presented by President Whyte-Gómez avoids the establishment of different categories among the Parties to the future Convention and keeps open future accession by States that possess or host huclear weapons as described above.

States that possess nuclear weapons and some of their allies have repeatedly voiced opposition to the prohibition treaty, while non-nuclear-weapon States have become incresingly critical of what they regard as lack of political willl on the part of the possessor States to honor their nuclear disarmament obligations under Article VI of the NPT.

The success of the Convention and its ability to evolve over time into a universal instrument codifying the repudiation of nuclear weapons will depend on the response of public and specialized opinion worldwide, particularly in States that remain initially outside its purview. States that become Parties to the Convention, as well as civil society organizations supporting it have a special responsibility to work toward its universalization.

There is great expectation on the part of the 132 States and the many non-gpvernmental organizations that participated in the first part of the Conference last May for the continuation of the work on the elaboration of the new Convention. It must be kept simple and clear and at the same time be inclusive and open to universal participation.

72 years since the start of the proliferation of nuclear weapons and 47 years since the entry into force of the NPT, the continued existence of nuclear weapons and the frightening prospect of their use still haunt mankind. The opportunity to establish an international legal norm prohibiting such weapons must not be squandered.

* Sergio Duarte was the UN High Representative for Disarmament Affairs with the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs (2007-2012). He was the President of the 2005 Seventh Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. A career diplomat, he served the Brazilian Foreign Service for 48 years. He was the Ambassador of Brazil in a number of countries, including Austria, Croatia, Slovakia and Slovenia concurrently, China, Canada and Nicaragua. He also served in Switzerland, the United States, Argentina and Rome.