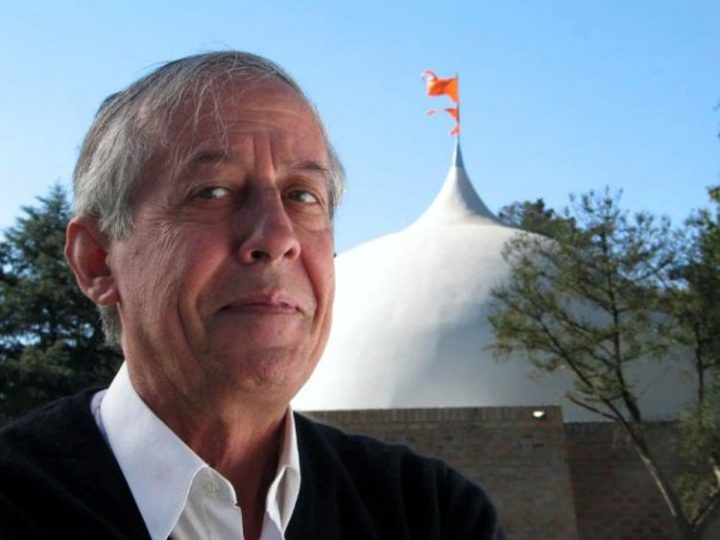

It took Trudi Lee Richards 12 years to finish writing about Silo, the pen name of Mario Rodriguez Cobos. This remarkable man born in Argentina was a brilliant thinker, prolific writer, champion gymnast, and charismatic speaker who attracted a following in the 1960s for his revolutionary approach to nonviolent social and personal transformation. He developed the current of thought known as New or Universalist Humanism, he founded the all-volunteer international Humanist Movement, which by the year 2000 had over a million adherents on five continents. In the new millennium he published Silo’s Message, inspiring the birth of the international Community of Silo’s Message and the building of Parks of Study and Reflection around the world. When the Humanist Movement carried out the World March for Peace and Nonviolence in 2009, he spoke on Active Nonviolence before the Berlin Nobel Peace Laureates’ Summit.

Who is Silo, the so-called “Sage of the Andes” and why should somebody who has never heard of him read his biography?

Silo is the pen-name of Mario Luis Rodriguez Cobos, a 20th-21st century writer, thinker and spiritual guide from South America. His story should interest anyone who has struggled with questions like these: why are we here, how can we end violence, does life end with death?

He was a completely ordinary person, born in 1938 in Mendoza, Argentina. He took over the family agricultural business at a young age, married a local girl, raised two sons, and wrote books in his spare time. He was known to his neighbors as a family man, a kind and friendly person with a great sense of humor and a love of strawberry ice cream. He died at home in 2010 surrounded by friends and family, having lived his whole life in the same small provincial city.

But Silo was also a remarkable human being, a widely traveled and world-renowned thinker and writer, poet and mystic. Many regard him as one of the most important spiritual guides of our times.

His wide-ranging legacy includes:

- Fifteen major books translated into more than 20 languages, as well as countless talks and shorter written works in multiple genres

- The Community of Silo’s Message, a worldwide spiritual current for peace and nonviolence, inspired by his last major written contribution, Silo’s Message

- The worldwide, all-volunteer Humanist Movement for social and personal transformation through active nonviolence

- Silo’s School, dedicated to the preservation and development of essential human knowledge

- The worldwide network of “Parks of Study and Reflection,” sanctuaries of peace and nonviolence on five continents, open to human beings of all backgrounds and beliefs

Why is Silo called the “Sage of the Andes”?

I first encountered the term “Sage of the Andes” in Daniel Zuckerbrot’s documentary of that name. The name is apt – throughout his life, from childhood on, the Andes were an important spiritual center of gravity for Silo. In 1969 he gave his first public talk at Punta de Vacas, the remote spot near Mt. Aconcagua that years later would become Punta de Vacas Park of Study and Reflection. It was there that Silo would live and work with the members of his School in the new millennium, until shortly before his death in 2010.

You have said that stumbling on the Humanist Movement helped you find your own way out of suffering. What changed for you when that happened?

It was crazy. Until I met the Humanists in 1984, I was basically scared of everything – of sickness, of death, of losing the people I loved. After I started working with them, my obsessive fear inexplicably vanished.

The Cold War was at its height, and I was terrified that the Bomb would fall and I’d have to watch my beloved baby twins burn alive before my eyes. I was desperate, and these Humanists said we could change things – so I joined them.

Working with them turned my energy around. Going to the street to talk to people about peace and nonviolence, I stopped focusing on myself and my own problems. I began to turn my energy outward, toward others, toward the world. This transformed my experience of who I am: it put me in touch with something inside me, an inner strength and goodness that I didn’t know I had.

As Silo often said, there’s “something great and good” inside every one of us. That “something” is inside us – but it’s also bigger than we are. It’s strong, wise, kind and joyful, and totally unafraid.

I think most of us suffer because we aren’t in touch with what is great and good inside us. When anything goes wrong, we see ourselves as helpless victims of misfortune, or we feel like we must have done something wrong…

But when we get in touch with our inner strength and goodness, and begin calling on it, exercising it, our connection with it grows stronger and stronger – just like muscles do when we use them. And this helps us begin to build a new center of gravity. Then we begin to feel that we are OK – that we don’t have to look for help from outside, from other people or from some external god – because all the help we need is already inside us!

Trudi Lee Richards is a poet, writer, and translator.

Why did you spend 12 years writing a biography of Silo, and how has writing this book affected your life?

Losing my obsessive fear was an enormous relief, an incredible gift. It freed me to give my best, which gave me great joy. After that I wanted nothing more than to share my good fortune with others. I tried in many ways over the years, working for personal and social change through active nonviolence in the Humanist Movement.

But when Silo’s Message came out, it touched me more deeply than any of his other work. It was the gift of gifts. It opens up a very simple, accessible way of going deep inside ourselves – making contact with the Sacred and the Profound. It shows us that we are not separate or alone, that we are all deeply connected. That anything is possible when we live with unity.

This little book is so universal, so accessible, that I knew that it could help many people, if only they knew about it.

Then I realized that if I wrote Silo’s story, I might help spread awareness of his work. I love to write, so it would be a very unitive, joyful way for me to give something back – to make an important contribution to spreading this beautiful work, which is so needed right now. I wrote to Silo, proposing that I write his biography – and to my delight he said yes!

Actually writing the book has been a whole process – enthralling, frustrating, challenging, and humbling. Silo warned me that he wouldn’t help, and he asked me not to bother his family. There was little written about his life – but there were many people who knew him, so I did a lot of traveling and emailing. I reached out to anyone I could find who knew him and was willing to share their experience.

It was more complicated than I could have imagined! I soon realized that there were so many contradictory stories about Silo that there was no way I could tell the “truth” – in the sense of giving an accurate, objective account of his life. I tried several different approaches, threw away tons of material. For a while I thought the only answer was to write a novel. In the end, however, I decided I could just weave all these stories together around a framework of verifiable “facts,” making it clear that nothing I wrote was the absolute truth – each story, each anecdote, was simply one person’s perception, one person’s memory, inevitably tinged by their own experience.

Why did you call your book On Wings of Intent?

That name is connected with a central theme of Silo’s: failure. In 1969, Silo’s friends traveled all over Argentina and Chile, spreading word that Silo would speak at Punta de Vacas, high in the Andes. They said his teaching was “for the failures.” Some 200 young people showed up, and Silo spoke to them on The Healing of Suffering. Decrying the snowballing violence in the world, he exhorted his listeners to find peace within them and carry it to others.

That talk launched the Humanist Movement that has been working since then to bring peace to individuals and society through active nonviolence.

Thirty years later, in 1999, Silo spoke again at Punta de Vacas. In that talk he acknowledged that the Humanist Movement had failed, and that anti-humanism had triumphed – at least for now. At the same time, however, something new was being born: “the first planet-wide civilization in human history…”

In 2004, Silo spoke at Punta de Vacas for the third time, before thousands. His opening words made everyone burst into gales of laughter:

“We have failed,” he said, “but we keep insisting!”

When everyone quietened down, he went on with some of the most profoundly moving words he would ever speak:

“We have failed, and we will continue to fail not just once but a thousand times again, because we ride on the wings of a bird named Intent that soars above frustration, weakness and pettiness…”

Later in the same talk he said, “Yes, there will be peace, and out of necessity it will be understood that the outline of a universal human nation is taking shape.”

I was there, standing on that arid mountainside, when he spoke those words – and when he said, “There will be peace,” we all began weeping and laughing and cheering with joy and relief.

Not that we thought he was a prophet – but he was our friend, someone we loved and tremendously esteemed. We had seen him work tirelessly for decades in the face of apparently hopeless odds, without ever giving up, always sharing his “certainty from experience” that all would be well, that “if you repeat your acts of internal unity, nothing can detain you…”

That’s why this biography is called On Wings of Intent. Because more than anything, what drove Silo was his fierce, profound, yet patient intentionality. He never gave up, even after repeated failure, in the face of impossible odds and the most horrific violence.

Silo’s intentionality was rooted in his clear and unshakable Purpose, in his profound faith in Life and in the Future – a faith that was not naïve, but based on living experience. That same intentionality continues to inspire untold numbers of his followers today who continue to face violence with nonviolence, hatred with love, bitterness with reconciliation.

In our society, where success is so highly valued, Silo’s willingness to admit that the project of Humanizing the Earth had failed was very unusual. Why did he take that stance?

Silo saw that success just isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. We think we’ll be happy if we succeed – but the struggle for success always ends in frustration. If we don’t succeed, we suffer because we failed. If we do succeed, our happiness is always temporary and provisional – we know things always change, and loss will come, one way or another.

The big question is how to be happy from within, without depending on outer success. Silo said suffering comes from contradiction – and that we can only learn to overcome contradiction if we give up on success, if we admit that we are failures.

In his talk on “The Search for an Object,” he spoke about failure and contradiction and the work of the “empty hand”:

“Until you recognize that you have no way out, that your life is a vicious circle, a continual contradiction without meaning, you can’t begin to work [on yourself] seriously. It’s as simple as that… We want to overcome contradiction, overcome suffering. We define our work as the work not of the full hand, but of the empty hand…”

By way of illustration, he went on to tell a story about monkeys:

“You know how they catch certain monkeys: they put some rice in a tree trunk with a small hole, then the monkey puts his hand in the hole, takes the rice, and then can’t get his hand out again. He sees that they’re going to catch him, but he doesn’t want to let go of what he has in his hand. The monkey suffers from a great contradiction…”

Silo often spoke of the importance of overcoming pain and suffering, and he also talked about active nonviolence and personal development as a means of achieving social change. Why were these themes so important to him?

Silo saw people all around him trying to end suffering in a one sided way.

Some focused on social change, trying to change the world but neglecting their own inner, personal and spiritual needs. They would end up burning out and giving up in resentment and disillusionment.

Others, the “spiritual seekers,” strove to end their own personal suffering, but ignored the suffering of others and the growing crisis in the world around them. They became isolated and neurotic from obsessing about their own personal problems. I was one of those.

Silo knew neither approach worked. Seeing life as a global structure, where the inner and the outer are two sides of the same coin, he knew that the only way to bring about deep and lasting change, either personal or social, was to work for both at the same time. Because we really are not separate and isolated – we live in the same world, we share the same essential humanity.

That’s why “treating others as you want to be treated” is so central to Silo’s teaching. Only that way can you help others and yourself at the same.

In Silo’s Message there’s a wonderful experience called “Wellbeing,” where we come together to ask the best for friends and loved ones who are going through difficult times. Whenever I participate in that experience, I feel better myself, because we really are connected, deep down. Treating others well is really treating myself well. That’s the way to live a coherent life – true to myself, true to others, true to the world.

Book presentation in Europe:

- 07.05.2017, Park of Study and Reflection Toledo, Spain

- 08.05.2017, Centro de enseñanzas alternativas in Malaga, Spain

- 10.05.2017, Espacio Ronda in Madrid, Spain

- 11.05.2017, Casa del Libro, in Barcelona, Spain

- 12.05.2017, Salita Spandau-Berlin, Germany

- 13.05.2017, Park of Study and Reflection Schlamau, Germany

- 14.05.2017, Park of Study and Reflection La Belle Idée, France

- 19.05.2017, Park of Study and Reflection Attigliano, Italy

Interview by Nina Siebenborn and Reto Thumiger

Trudi Lee Richards is a poet, writer, and translator living in Northern California. In the ’70s, when her BA in English Literature from Stanford University failed to resolve her perplexity about the meaning of life, she embarked on the search that would finally lead her to the work of Silo. Joining the Humanist Movement, she became a nonviolent activist, publishing an independent newspaper, leading weekly meetings, and traveling widely while raising her three children. In the early 2000’s she settled in northern California to write, reflect on life, learn to play Bach on the keyboard, and nurture a community of friends inspired by Silo’s Message. Her poetry and other publications, including Soft Brushes with Death, Experiences on the Threshold, and Fish Scribbles, are featured on www.wingedlionpress.org along with the work of other Siloists from around the world.