By Amy Goodman and Denis Moynihan

OCCUPIED WESTERN SAHARA—Sultana Khaya’s eyes don’t match perfectly. One of them is artificial. In 2007, a Moroccan police officer rammed his baton into her eye socket while she was peacefully protesting with fellow college students. He then gouged her eye out with his hand.

Sultana is Sahrawi (Sah-ha-RAH-wee), the indigenous population native to Western Sahara. Occupied by the Kingdom of Morocco since 1975, Western Sahara is commonly referred to as Africa’s last colony. The Sahrawis are in a protracted struggle for self-determination, and face terrible repression by Morocco.

The United Nations has called for a referendum that would allow Sahrawis to decide whether to remain a part of Morocco or become independent, but Morocco has blocked the vote for over 25 years.

Western Sahara is a territory rich in natural resources: fishing, phosphates and the prospect of offshore oil. Thousands of Sahrawi have been tortured, imprisoned, killed and have disappeared since the occupation began over 40 years ago. To understand the depth of the Sahrawis’ commitment to independence, their courage in the face of brutal oppression, one need only look into Sultana Khaya’s eyes.

We went to Laayoune, the capital of Western Sahara, just after the United Nations climate summit (COP22) wrapped up last week in Marrakech, Morocco. We were the first foreign television news crew to get into Western Sahara in recent years. We were followed constantly, on foot and by men on motorbikes and in cars. They stood outside our hotel night and day. Moroccan secret police came to our hotel at midnight on our first night, a “strictly routine” visit, they told us, “to protect us.” Foreign journalists who do get in are often promptly expelled if the Moroccan intelligence agents see them interviewing pro-independence Sahrawis.

The Sahrawi activists who spoke to us did so at great risk to their own personal safety. We met them primarily in their apartments, where couches line the walls in traditional Saharan fashion, with the Sahrawi tea, “at-tay,” prepared over embers.

We stopped for lunch at a virtually deserted restaurant on the edge of town. About 80 men and some women arrived abruptly. Most wore traditional Sahrawi garb, and many waved the official flag of the occupying state, Morocco. They moved into the restaurant, filling every nearby table, effectively cornering us. A dozen plainclothes agents, one wearing an NYPD baseball cap, were there coordinating, constantly on their cellphones. Outside, security agents’ cars blocked ours. Several of the men seated near us seemed very agitated, and we feared this bizarre display could turn violent. They surrounded us as we left. While almost none in the mob spoke English, they unfurled several glossy vinyl banners with slogans in English like “Shame on Democracy Now!” The banners were identical in design to ones displayed after U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon condemned the Moroccan presence in Western Sahara as an occupation.

As we left, it became apparent why the crowd descended on us when they did. Sultana and other Sahrawi activists had organized a demonstration in the city center. The mob that surrounded us prevented us from getting to the protest, which was violently attacked by Moroccan plainclothes police. Brave Sahrawi independent journalists who operate under extreme threat in Western Sahara managed to capture video, which they later shared with us. That day’s violent repression was all too typical.

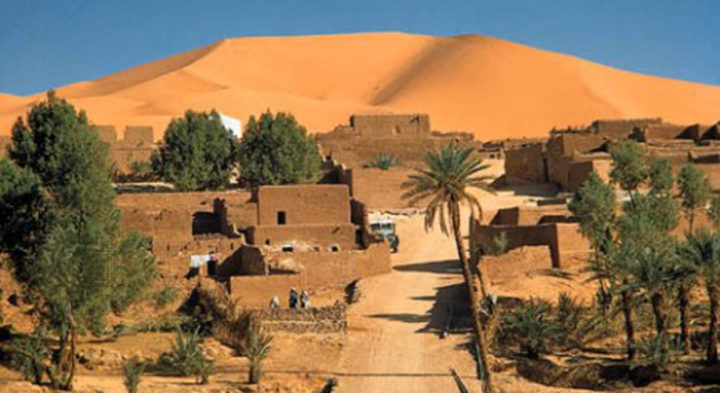

One video shows a handicapped man, Mohamed Alouat, director of a school for the handicapped, holding the flag of independent Western Sahara, a government in exile in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, where around 100,000 Sahrawi refugees live.

Police attack Alouat, tear the flag from his hands, and drag him off.

Sultana and other women shout at the plainclothes officers. A group of at least 20 of the men swarm around the Sahrawi women, pushing them into a side street, away from the main thoroughfare. They gang up on the women. They beat one of them, Aziza Biza, a member of the Sahrawi Women’s Forum, in her kidney and stomach with a walkie-talkie. She said later that they choked her with her traditional melfa dress until she passed out on the ground. The police continue pushing other women against a wall and sexually assaulting them by grabbing and twisting their breasts. The agents see a man recording the assault from a nearby rooftop and began throwing rocks at him.

We met the injured men and women that evening, and recorded their accounts. The women showed us their injuries, describing how the police twisted their breasts and nipples, inflicting intense pain and bruising them. Aziza was faint, throwing up repeatedly.

Later that night from our hotel window, we saw police in riot gear throwing rocks at Sahrawi protesters. The Sahrawi people are undeterred in their nonviolent struggle for self-determination. You can see the commitment to that struggle in the eye of Sultana Khaya.