Belgium delegates reached 11th-hour consensus, which grants the Court of Justice of the European Union the ability to rule on final inclusion of ISDS.

The controversial Canada-European Union trade agreement that many declared “dead” now appears to be rising from the ashes, as officials announced Thursday that they have reached a last-minute consensus.

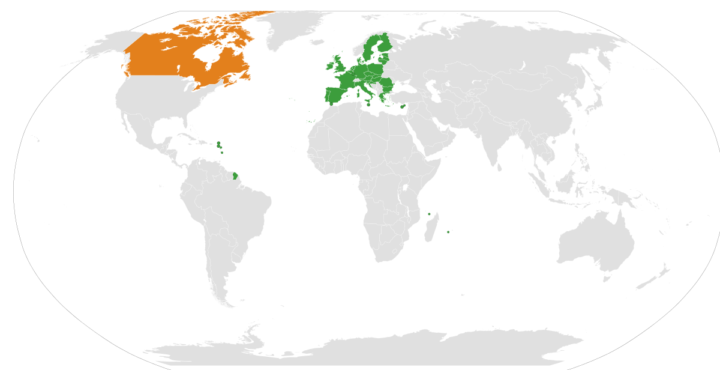

Earlier this week, trade delegates from the Belgian region of Wallonia rejected the Comprehensive Economic & Trade Agreement (CETA) out of concern that certain provisions, particularly the Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) system, inflate the power of multinational corporations and undermine standards protecting labor, the environment, and consumers.

After it was reported that Canadian Prime Justin Trudeau had scrapped his travel to Brussels and the planned Thursday signing ceremony was officially cancelled, Belgium Prime Minister Charles Michel announced that his country had reached agreement over a new text, which needs to be re-approved by the remaining 27 EU member nations.

Though details of the updated agreement are still emerging, Wallonia Minister-President Paul Magnette, who had led opposition to the agreement, told reporters that his resistance had “yielded huge results,” AFP reports.

“We always fought for treaties that reinforced the social and environmental standards, protect the public services and that there is no private arbitration [in dispute settlements],” he said, referring to the ISDS provision. “All this is achieved as of now.”

“I am sorry for all the other Europeans we made wait and for our Canadian partners. But if we took a bit of time, what we achieved here is important, not only for Wallonia but for all Europeans,” Magnette said.

According to Belgian public broadcaster RTBF, and reported by the EU Observer, under the new terms, the Belgians “agreed to a general safeguard clause, which would allow any regional entity within a federal structure like Belgium’s to withdraw the country from CETA. They also want a contested investment protection system to become a real public court, amid fears that the mechanism, in its current shape, is biased towards corporate interests. Farmers would also see special protection and support measures triggered if they are hurt by Canadian competition.”

But political economist Gabriel Siles-Brügge explained that the new text grants the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) the ability to rule on final inclusion of ISDS, which he said, “could backfire.”

In a press statement, the Council of Canadians explained further:

The Council of the European Union will still have to formally agree to the deal and the 751-member European Parliament will need to ratify it as well. Following that, significant portions of CETA would be provisionally applied before the 28 EU member states and 38 parliaments have the opportunity to vote on the deal. That said, a German constitutional court ruling on October 13 means that CETA’s most controversial provision – its investment court system (ICS) provision – cannot come into force until approved by all member states and parliaments.

This means that the ICS provision cannot be implemented until after the 2-3 year process of member state votes, and the hope and likelihood that it will not secure the unanimity needed to ever come into force.

Given all this, as Council of Canadians chairperson Maude Barlow put it, the process “will not be an easy ride even now. Horrible flawed deal and process.”

Indeed, at the same time that representatives were cobbling together the 11th-hour agreement, critics of the deal rallied outside of the EU Commission with banners declaring: “The more you insist, the more we resist.”