An inflated view of Russia’s power, influenced by its role in Syria, could hasten further destructive conflict.

By

The assaults on rebel-held districts of Aleppo by Russian and Syrian government forces have been deadly, not least the targeting of hospitals. These have earned strong criticism from United Nations staff as well as western governments. In the case of Washington, such criticism can all too easily seem hypocritical in the wider context of the United States-led war on ISIS which has led to at least 30,000 of the movement’s supporters being killed in Iraq and Syria. Civilian casualties, according to Airwars, are over 1,600. The same judgment applies to Britain with its arming of Saudi Arabia as that state continues to wage its hugely damaging war in Yemen.

In Syria, the breakdown of talks between the respective foreign ministers John Kerry and Sergey Lavrov is a serious development. Without re-engagement there appears little hope of any new ceasefire agreement. Lavrov’s suggestion of a two-day pause in the attacks, however, may indicate that some inside the Kremlin are beginning to worry that events in Syria may slip out of control. This, in turn, raises the question of what motivates Vladimir Putin in his support of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. This can best be understood in terms of Russia’s experience since the late Soviet era, before the end of the cold war in 1989-90.

The Russian context

In the early 1980s, during a particularly dangerous period of east-west confrontation, the Soviet Union underwent three leadership crises in quick succession. The death of Leonid Brezhnev in November 1982 was followed by that of his successor, Yuri Andropov, in February 1984, whose own successor Konstantin Chernenko was already ill and died in March 1985. Thus did Mikhail Gorbachev come to inherit a state in trouble: a quasi-empire of disparate countries, unable remotely to match Nato in its defence spending, and embroiled in an unwinnable war in Afghanistan.

Within three years, Gorbachev – having withdrawn Soviet forces from Afghanistan – had begun attempting to change the entire edifice of the old USSR through a combination of perestroika (reform) and glasnost (openness). In the event, the system was not for saving and came apart spectacularly in the early 1990s. This encouraged the west to treat post-Soviet Russia with near contempt. Moscow chaotically embraced ‘turbo-capitalism’, with terrible consequences for the health of the nation amidst rampant and accelerating inequality.

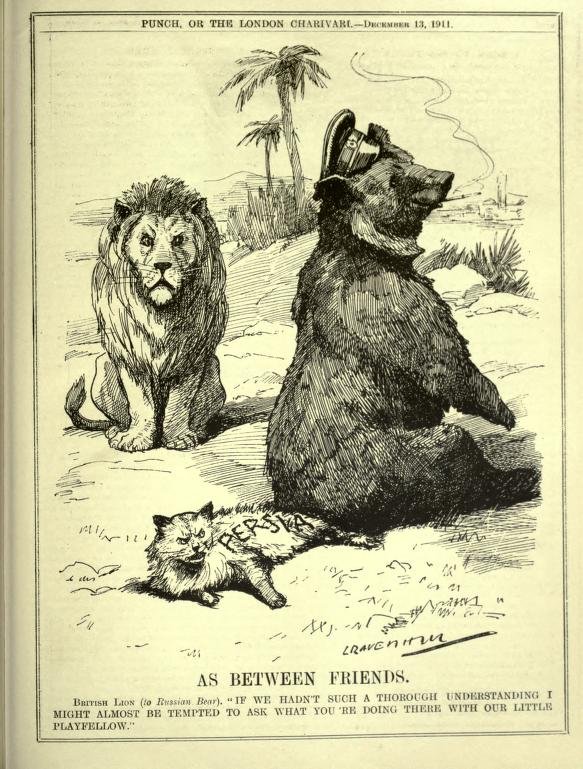

Both the Afghanistan disaster and the chaos of the 1990s are embedded in the culture and thinking of older Russians. But it is the contempt from the western world that is most bitterly recalled, and its memory that Vladimir Putin plays on relentlessly as he claims to be building a new superpower. What makes this worse is the manner in which Nato and the European Union have been seen as encroaching on what in Russia is termed the “near-abroad”. The process has extended beyond the east European states that joined Nato to the forging of close links with Georgia and especially Ukraine. At the same time Moscow was also concerned by its evident loss of influence across the Middle East.

All this goes a long way to explaining what is seen in the west as out-and-out adventurism, first in Georgia and more recently in Crimea and eastern Ukraine, but in Russia as fully legitimate. This contrast of views allows western politicians to peddle the line that their bloc is in a new era of competition with a reawakened superpower. While there may be some element of truth in this, the line is certainly useful for the western military-industrial complex: it provides a welcome enemy whose threat demands that military budgets be shored up.

Most people in western Europe who are asked to estimate Russia’s economic and military power relative to the United Kingdom, France or Germany, are likely to say that Russia is hugely stronger – one of the major economic powers in the world and doubtless able to match even a cluster of western European states. This is a myth, even if a congenial myth to any western arms company and not a few western politicians. Russian GDP is actually less than half of that of the UK or France, not even a third of that of Germany, a quarter of Japan’s, a tenth of China’s and barely a sixteenth of that of the United States. International Monetary Fund (IMF) figures published in April 2016 show that Russia’s nominal GDP rank is fourteenth in the world, behind Australia, South Korea, Spain, Canada, India and Brazil.

This criterion isn’t everything. It’s true that low oil prices have been particularly damaging for Russia’s economy, and that the country does spend a much higher proportion of its GDP on the military (though even that still places it behind China, the UK and France and a very long way behind the United States). Moscow has certainly increased its level of military spending, both on general budgets and specific overseas deployments, and is developing new equipment, not least aircraft and tanks. Yet the rate of development is slow, the navy has far too many obsolete ships, and the army, apart from some competent and well-equipped special forces, is regarded by many independent observers as inadequate. Where Russia has successfully sought to develop some degree of equivalence is in nuclear weapons, but this is already stimulating a thorough upgrading of US nuclear forces.

The president, though, remains determined to promote Russia as a superpower and retains popularity at home despite the already clear economic costs. He is successful in large part because of that 1990s background, but this does not mean his approach is without considerable risk. The military posture in Syria is a specific case in point, in a way which has a resonance with Afghanistan 30 years ago.

The present danger

Russia regards it as essential for its influence in the Middle East and its more general status that Bashar al-Assad must survive in Damascus or eventually hand power to a successor regime that is also acceptable. The problem for Russia is that Assad or his successors cannot maintain control without long-term Russian aid, since support from Iran and Hizbollah simply will not be enough. Thus, if Russia wants to avoid an Afghanistan-like quagmire it has to get out soon – but to do so risks the collapse of the Assad regime and serious damage to its prestige (and even, perhaps, to Putin’s own position).

Moreover, one effect of the indiscriminate bombing by the Russian airforce may be to encourage some members of smaller and less extreme militias to flock to the cause of much more radical (and effective) Islamist groups. And there is a huge risk that the Russian air-war in Syria will increase the risk of Islamic radicalisation within Russia itself (where over 16 million Muslims live across the country).

The immediate dynamic is dangerous enough. It is convenient for many in the west to build up Russia as the new threat, already an uncomfortably prominent part of the current Hillary Clinton vs Donald Trump battle for the US presidency. At the same time, this very antagonism is helpful to Putin because it demonstrates that Russia is considered to be a force to be reckoned with.

The result is a high state of tension that is likely to persist. It is reminiscent of that troubling acronym “AIM” – denoting Accidents, Incidents and Mavericks – which has been discussed in earlier columns. All three, separately and in combination, can lead to an escalation, which sharp uncertainty can take to something worse (see “Russia in Syria, and a flawed strategy“, 1 October 2015).

For that reason alone, the sooner there is a return to any kind of diplomatic interchange the better. Meanwhile it would be no bad thing if western politicians put rather more effort into countering the view that Russia is so powerful. Vladimir Putin might well like that view, and that alone is one good reason to avoid it.