We go to Bogotá to get reaction to the selection of Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos as this year’s Nobel Peace Prize winner for his role in pursuing a peace deal to end the nation’s 52-year-old civil war. The move comes after Colombians rejected the peace deal just this past Sunday in a nationwide referendum. Nobel Peace Prize Committee. “It would have been better … if the [peace prize] had been granted both to President Santos and to Rodrigo Londoño, the head of the FARC,” says Daniel García-Peña, who was Colombia’s high commissioner for peace from 1995 to 1998. He is a professor of political science at the National University in Bogotá. García-Peña is also the founder of the organization Planeta Paz, or Planet Peace, dedicated to building grassroots participation in the Colombian peace process.

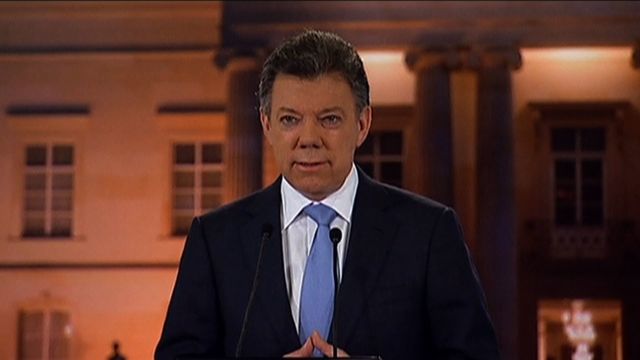

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos has been chosen to receive this year’s Nobel Peace Prize for his role in pursuing a peace deal to end the nation’s 52-year-old civil war. The move comes after Colombians rejected the peace deal just this past Sunday in a nationwide referendum. Nobel Peace Prize Committee Chairperson Kaci Kullmann Five announced the award earlier this morning.

KACI KULLMANN FIVE: The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided to award the Nobel Peace Prize for 2016 to Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos for his resolute efforts to bring the country’s more than 50-year-long civil war to an end, a war that had cost—has cost the live of at—lives of at least 220,000 Colombians and displaced close to 6 million people. The award should also be seen as a tribute to the Colombian people, who, despite great hardships and abuses, have not given up hope of a just peace, and to all the parties who have contributed to this peace process. This tribute is paid not least to the representatives of the countless victims of the civil war.

AMY GOODMAN: That was the Nobel Peace Prize Committee announcing this morning that this year’s award goes to Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos for his role in pursuing a peace deal to end the nation’s 52-year-old civil war. The conflict began in ’64, has claimed 220,000 lives. More than 5 million people have been estimated to have been displaced. Kullmann Five was asked whether the Nobel Committee considered including the leader of the FARC rebel group in the award; she refused to comment on the selection process.

For more, we go now to Bogotá, Colombia, where we’re joined by Daniel García-Peña. He was Colombia’s high commissioner for peace from ’95 to 1998, a professor of political science at the National University in Bogotá. Professor García-Peña is also founder of the organization Planeta Paz, or Planet Peace, dedicated to building grassroots participation in the Colombian peace process.

We welcome you back to Democracy Now! Your response to the award to President Santos?

DANIEL GARCÍA-PEÑA: Well, in the first place, I think that it’s very welcome news. It highlights the fact that the Colombian peace process has had much more support in the international community than it has had here in Colombia. And I think the hope is that this award will help motivate not only President Santos, that has been committed to this process, but all the parties involved, so that the process can continue despite the negative vote of the referendum.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And where does Colombia go from here, after the rejection of the peace process, in terms of the potential resumption of hostilities?

DANIEL GARCÍA-PEÑA: Well, the good news is that all the parties, even those that have voted for the “no,” including ex-President Uribe, have stated that they do not want a return to the war. The ceasefire that was agreed upon has been continued. And talks began a few days ago between the ex-president, Uribe, and those that supported the “no” in the referendum, with President Santos and the negotiating team to see what they can figure out to move the process forward. There is still no clear indication of how that can take place, of what the specific actions can be taken. But I think that the first reaction on all parties, that we look for solutions to move forward, is positive.

And the reaction of the Colombian people has also been very important. There was huge marches in Bogotá and throughout Colombia the day before yesterday that demanded that the process continue. So we all hope that this news of the Nobel Peace Prize can help to move things in the right direction.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And in about a minute that we have left, your reaction to President Santos receiving the award, but not the leader of the FARC?

DANIEL GARCÍA-PEÑA: Well, I was a bit surprised. I think that there’s no doubt that President Santos has had a huge role. His perseverance, his dedication is very important and merits the recognition. But I also think that it’s important to recognize the decision on the part of the FARC. Their role in all of this has been very, very important from the beginning. And their reaction, in fact, to the defeat of the referendum has also, in my view, been very important. They’ve state over and over again that they do not want to return to war, that they are committed to peace. So I think it would have been better, in my view, if the award had been granted to both President Santos and to Rodrigo Londoño, the head of the FARC.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, less than half of the population voted. What was it? Maybe 40 percent. What is your sense, if more people had been involved?

DANIEL GARCÍA-PEÑA: Well, it’s hard to say, but I think that there’s very specific issues that you can look at. The fact is that the Hurricane Matthew, that is now hitting the coast of the United States, was just beginning in the Caribbean. And the day of the vote, the whole northern coast of Colombia was swamped by rain, and so the voter turnout was the lowest precisely on the Atlantic coast, while the—that area voted overwhelmingly for the “yes.” But if the voter turnout had been just the same—the same degree that it had been throughout the country, maybe the vote would have been different.

AMY GOODMAN: Daniel García-Peña, we want to thank you for being with us, Colombia’s high commissioner for peace from 1995 to ’98, professor of political science at National University in Bogotá and founder of Planet Peace.