A letter signed by a great number of professors of international law and researchers entitled “A plea against the abusive invocation of self-defence as a response to terrorism” has been circulating on the web for a few weeks.

Among the signatories, of which there are more than 220 professors and almost 50 assistants/researchers (see the list available here as of July 22, regularly updated by the Centre de Droit International de l´Université Libre de Bruxelles, ULB) , we find distinguished members of the international law community as well as younger researchers and assistants. The objective of this collective initiative is to challenge the use of the legal plea of self-defence by several States in the context of the war against ISIS.

The United Nations Charter is extremely clear on the unique exception to the prohibition of the use of force since 1945: self-defence (and military operations authorized by the Security Council under Article VII of the Charter). However, since 9/11, several interpretations made by the United States and its allies have tried to legally support unilateral military operations in the territory of a State without the prior consent of its authorities. In a recent note published on the European Journal of International Law (EJIL) website, we read that: “Particularly since 9/11, several States have supported a broad reading of the right to use force in self-defence, as allowing them to intervene militarily against terrorists whenever and wherever they may be. A consequence of that conception is that any State could be targeted irrespective of whether that State has ‘sent’ the irregular (in this case terrorist) group to carry out a military action or has been ‘substantially involved’ in such an action”[1].

The use of force in self-defence must be exercised in conformity with the conditions laid down in the UN Charter and international law. On this very particular point, it must be recalled that France presented a quite surprising draft resolution to the Security Council after the Paris attacks of November 13, 2015 (see the full text of the “blue version” circulated among delegations) avoiding any reference to the Charter in the operative paragraphs: it is possibly a great first for French diplomacy at the United Nations[2].

The text of the letter (available here) in French, English, Portuguese, Spanish and Arabic) considers, among others arguments, that:

“Thus, numerous military interventions have been conducted in the name of self-defence, including against Al Qaeda, ISIS or affiliated groups. While some have downplayed these precedents on account of their exceptional nature, there is a serious risk of self-defence becoming an alibi, used systematically to justify the unilateral launching of military operations around the world. Without opposing the use of force against terrorist groups as a matter of principle — particularly in the current context of the fight against ISIS — we, international law professors and scholars, consider this of self-defence to be problematic. In fact, international law provides for a range of measures to fight terrorism. Priority should be given to these measures before invoking self-defence”.

For the signatories of this letter,

“…. we consider that terrorism raises above all the challenge of prosecution and trial of individuals who commit acts of terrorism. A variety of legal tools are available in this respect. They relate first and foremost to police and judicial cooperation (chiefly through agencies such as INTERPOL or EUROPOL), aiming both at punishing those responsible for the crimes committed and preventing future occurrence of such crimes. Although there is certainly room for improvement, this cooperation has often proved effective in dismantling networks, thwarting attacks, and arresting the perpetrators of such attacks. By embracing from the outset the ‘war against terrorism’ and ‘self-defence’ paradigms and declaring a state of emergency, there is a serious risk of trivializing, neglecting, or ignoring ordinary peacetime legal processes”.

It must be noted that this letter is open for signatures by international law scholars and researchers around the until the 31st of July. The text recalls a certain number of very clear rules that diplomats in New York know better than anyone, despite the ambiguous interpretations made by some of their colleagues, in particular since the beginning of airstrikes in Syria, without the consent of its authorities[3].

This collective document also states that:

“…, the maintenance of international peace and security rests first and foremost with the Security Council. The Council has qualified international terrorism as a threat to the peace on numerous occasions. Therefore, aside from cases of emergency leaving no time to seize the UN, it must remain the Security Council’s primary responsibility to decide, coordinate and supervise acts of collective security. Confining the task of the Council to adopting ambiguous resolutions of an essentially diplomatic nature, as was the case with the passing of resolution 2249 (2015) relating to the fight against ISIS, is an unfortunate practice. Instead, the role of the Council must be enhanced in keeping with the letter and spirit of the Charter, thereby ensuring a multilateral approach to security /…/ However, the mere fact that, despite its efforts, a State is unable to put an end to terrorist activities on its territory is insufficient to justify bombing that State’s territory without its consent. Such an argument finds no support either in existing legal instruments or in the case law of the International Court of Justice. Accepting this argument entails a risk of grave abuse in that military action may henceforth be conducted against the will of a great number of States under the sole pretext that, in the intervening State’s view, they were not sufficiently effective in fighting terrorism”.

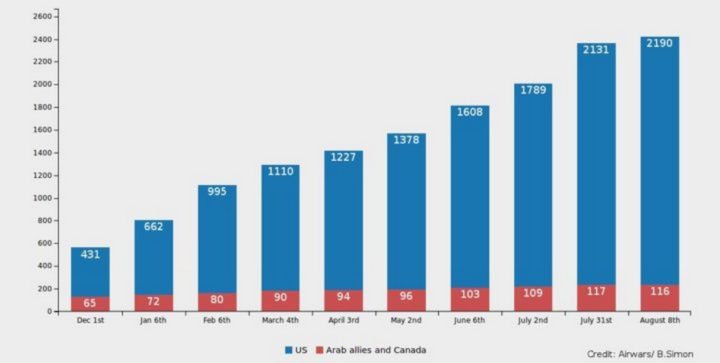

It must be noted that, in February 2016, Canada’s new authorities decided to cease airstrikes in Syria and Iraq. We read in this official note produced by the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) that: “In accordance with Government of Canada direction, the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) ceased airstrike operations in Iraq and Syria on 15 February 2016. From their first sortie on 30 October 2014 to 15 February 2016, the CF-188 Hornets conducted 1378 sorties resulting in 251 airstrikes (246 in Iraq and 5 in Syria), expended 606 munitions and achieved the following effects: 267 ISIS fighting positions, 102 ISIS equipment and vehicles, and, 30 ISIS Improvised Explosive Device (IED) factories and ISIS storage facilities”.

In 2015, a Canadian scholar concluded an extremely interesting article on Canadian airstrikes in Syria and Iraq in the following terms: “However, there is a further legal hurdle for Canada to overcome. Unless Canada can attribute ISIS´ attacks in Iraq to Syria, then the question becomes whether Canada may lawfully target ISIS, as a nonstate actor in Syria’s sovereign territory, using the ‘unwilling or unable’ doctrine to prevent ISIS’ extraterritoriality attacks against Iraq. This justification moves significantly away from the Nicaragua, Congo and Israeli Wall cases’ requirement for attribution. There appears to be a lack of consensus on whether opinion juris and state practice have accepted the “unwilling or unable” doctrine as customary international law. There is no escaping the conclusion that Canada’s air strikes on Syria are on shaky, or at least shifting, legal ground ”[4].

The signatories of this call, whose number increases from day to day, including scholars from different continents and age ranges, conclude by reaffirming that:

“The international legal order may not be reduced to an interventionist logic similar to that prevailing before the adoption of the United Nations Charter. The purpose of the Charter was to substitute a multilateral system grounded in cooperation and the enhanced role of law and institutions for unilateral military action. It would be tragic if, acting on emotion in the face of terrorism (understandable as this emotion may be), that purpose were lost”.

[1] See CORTEN O., “A Plea Against the Abusive Invocation of Self-Defence as a Response to Terrorism”, European Journal of International Law (EJIL Talk), July 14, 2016, available here .

[2] See our modest note published in France, BOEGLIN N., «Attentats à Paris : remarques à propos de la résolution 2249 », Actualités du Droit, December 6, 2015, available here . See also, after parliamentary debate in United Kingdom authorizing airstrikes in Syria, BOEGLIN N. «Arguments based on UN resolution 2249 in Prime Minister´s report on airstrikes in Syria: some clarifications needed », Human Rights Investigation, December 4, 2015, available here.

[3] On the notion of “unwilling or unable” State, justifying, for some diplomats, military operations on its territory without its previous consent, see: CORTEN O., “The ‘Unwilling or Unable’ Test: Has it Been, and Could it be, Accepted?” Leiden Journal of International Law, 2016. Full text of this article available here.

[4] See LESPERANCE R.J. , “Canada’s Military Operations against ISIS in Iraq and Syria and the Law of Armed Conflict”, Canadian International Lawyer, Vol. 10 (2015), pp. 51-63, p. 61. Full text of the article available here .