By Phil Wilmot for Waging Nonviolence.

Kenya is often praised as a beacon of democracy and stability in East Africa, but recent squelched demonstrations and recklessness by police have led Kenyans to question whether the benchmarks of their nation’s progress are being quickly eroded.

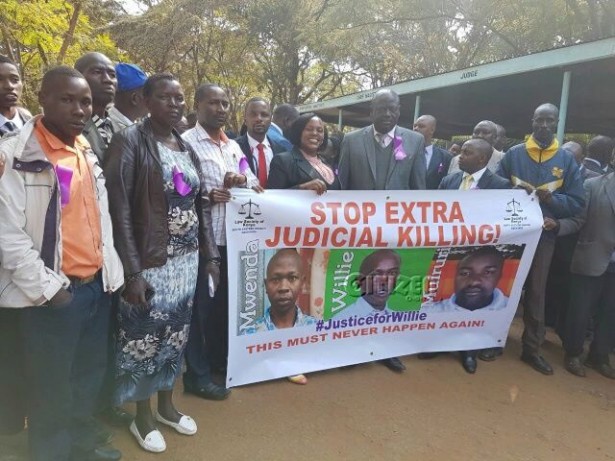

The discovery of human rights lawyer Willie Kimani’s corpse in a river 43 miles outside of Nairobi on Friday does President Uhuru Kenyatta’s government no favors in soliciting additional support from the Western world.

Kimani had represented client Josephat Mwenda — a motorcycle taxi driver — in a case at Kenya’s Mavoko Law Courts on June 23. After filing complaints against police over a bullet that struck his leg while operating his motorcycle, Mwenda faced allegedly fabricated drug and traffic charges — an effort by police to intimidate him into reneging his official complaints. Shortly after leaving court, the two men and their driver, Joseph Muiruri, were abducted.

A massive search ensued, spearheaded by International Justice Mission, or IJM, which was Kimani’s employer. State authorities were called to action, and word spread quickly to diplomats and larger media houses around the globe. The last person to have seen Mwenda was someone who spotted him — and perhaps others — calling for help from a metal container on a police base, where he tossed out a note on a piece of toilet paper saying, “Call my wife. I’m in danger.”

When little progress was being made in the search for the missing persons, lawyers crowded Kenya’s Supreme Court steps to demand an independent investigation. Kenya’s Flying Squad, accused of extrajudicial killings in the past, was the entity in charge of the investigation.

“The security system has completely failed in its constitutional mandate to protect Kenyan citizens,” said Law Society of Kenya president Isaac Okero, who lauded his colleague Kimani as an exemplary figure for those seeking to fulfill professional mandates as lawyers.

Peaceful demonstrations during the search were too little too late. When Kimani’s body was finally found, it had been stuffed in a sack, his hands still tied behind his back.

“Willie was joyful, funny and persistently positive,” said IJM communications fellow JoAnn Klandrud. “Although he worked in stressful situations under intense pressure, he was seemingly carefree. Over the past several years, police have been responsible for hundreds of murders.”

Few private investigators are truly chomping at the bit to involve themselves in matters like homicides by police. In 2009, Oscar Kamau Kingara and his colleague John Paul Oulu were ambushed in heavy Nairobi traffic, then killed by gunshot wounds. The assailants fled the scene. Kingara, a human rights lawyer and activist, had been investigating and documenting extrajudicial police killings.

The tragedies of Kimani’s death and Kingara’s earlier assassination are points of mourning for anyone anywhere who believes in justice. Unfortunately, they unveil a much broader and escalating concern across the region, where the atmosphere of fear engendered by regular disappearances and executions parallels that of Argentina in the late 1970s and early 80s.

“The incident of Kimani highlights a growing epidemic across East Africa,” said Chemisto Kubai, a public interest lawyer from Mt. Elgon.

According to Pacifique Nininahazwe, Burundi’s most widely-known activist, “Extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances have numbered in the hundreds since the April 2015 protests. [President] Pierre Nkurunziza is determined to exterminate all those who do not think like him.”

Justice for Kimani, Mwenda and Muiruri can only be fully attained if we treat their disappearance and subsequent torture not as a one-off incident, but as one that highlights the growing pattern of disappearances in the region. Unfortunately, a lawyer of significant notoriety from a large international human rights organization had to be among the victims for the movement against such injustices to earn a modest degree of global attention. This shows how dangerous the reality is for less visible activists whose abuse consistently falls upon deaf ears.

Monday protests

Fortunately, Kenya’s citizens are among the better organized populations of East Africa.

On Monday, activists and human rights groups began the work week with a march from Nairobi’s Freedom Corner to deliver petitions to the Supreme Court, police bosses and Parliament. Their demands included calls for the resignation of the inspector general of police and other security personnel. This coincided with a campaign using the hashtag #StopExtrajudicialKillings.

“We have announced that for one week, lawyers will effectively put down their tools,” Okero said. “We are so outraged that we are not in a state that we want to work in.” Boycotts of the courts are ongoing. During the first day, judges and lawyers all across the country stayed home.

The mood of demonstrations was set by the colors used. White T-shirts and coffins were covered in blood red lettering with slogans denouncing extrajudicial killings. According to Cidi Otieno, secretary general of the Coalition for Grassroots Human Rights Defenders, “The abduction and brutal murders of [Kimani, Mwenda, and Muiruri] were a big blow to our struggle … We asked the people to come out in large numbers.”

Across the border in Uganda, Solidarity Uganda and IJM arranged a solidarity vigil to grieve with their neighbors to the east and cast a light on the worrying trends of insecurity facing organizers and human rights defenders in their own country. Attendees, however, wanted to do more than hold a vigil.

“We need to do a physical march or something,” suggested an attendee representing the law firm Niwagaba & Mwebesa Advocates.

The sentiment was echoed by Simon Seyonga of the Center for Health, Human Rights and Development, who said, “We need to make much more noise, even when the space is tight.”

All of the tactics employed in these first few days after the discovery of tortured bodies are mere stepping stones toward attaining justice for those allegedly murdered by Kenyan policemen. Organizers in Kenya want to do more to politicize the funerals. Meanwhile, supporters of the deceased are planning to attend court in large numbers once suspects are arraigned.

Although the intensity of the situation feels overwhelming, a few adjustments can be made by organizers and human rights organizations to initiate the beginning of the end of political kidnappings, torture and extrajudicial killings in East Africa.

Expanding the definition of human rights defenders

Civil society organizations are part of the elite social class in East African countries. Although they may not earn salaries comparable with those of parliamentarians, they wear suits, carry smartphones and are seen driving private cars. Perhaps subconsciously, they develop programs centered on preserving people like them.

This is perhaps one reason why the classification of “human rights defenders,” or HRDs, has been restricted to the likes of employed people of higher social standing: lawyers, journalists and professionals in civil society organizations. There are many programs in East Africa run by organizations and coalitions that aim to protect HRDs, but they are often resistant to support activists and community organizers who may not have the social clout and media value of someone like Kimani. (This is obvious even in this campaign, given the way Mwenda and Muiruri have been largely overlooked.)

Activists on the frontlines of social change have few kind remarks for human rights organizations whose operating licenses — as one Ugandan activist put it — “rest in the hands of the oppressor.” Fear often prevents them from achieving their mission of protecting the most vulnerable.

According to Norman Tumuhimbise, a formerly abducted and tortured Ugandan activist, “Some [human rights organizations] are just moneymakers. They write reports, launch those reports in posh hotels, and then draft proposals for more funding.” He insisted that activists should make their activities transparent to the public to give them more credibility than those of other stakeholders working on similar objectives. “We activists should also blacklist some opportunistic civil society organizations. They are more evil than the state.”

The power of nonviolent social change has demonstrated time and again that victims of a problem do not need intermediaries. There is no reason the most vulnerable people should remain idle and expect civil society organizations with little sense of urgency to represent their interests. Intermediaries can sometimes be used, but “advocacy” is best waged when those most victimized by an injustice discover creative means that do not necessitate the public dialogue being led by voices that speak on behalf of the so-called voiceless.

Strengthening both rapid response and long-term efforts

According to Ugandan activist Hamidah Nassimbwa, who has been jailed on numerous occasions, the first step in engendering a culture of rapid response to disappearances is the educating of citizens in the villages and slums — not in fancy hotels where so many human rights functions take place.

“The public doesn’t know that it’s their role to say ‘no’ to human rights abuses,” she noted. “That’s why they pay when asked for money for police bonds, even thanking the police when their bonds are supposed to be free.”

Apart from educating communities on their rights, a network and system can be created to ensure that the disappeared is declared dead and a vigil is held within 24 hours of any abduction. This will pressure the state to either release the person they are torturing or use its resources to quickly trace the missing person.

Drastic times often call for hasty measures, but losing sight of the long view will only weaken the movement to put an end to the terrorizing of East African citizens.

The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo of Argentina, the Ladies in White of Cuba and the Saturday Mothers of Turkey teach us that many years of consistent, solemn demonstrations may be necessary to procure justice for the disappeared. Their movements also illustrate the importance of yielding to the actions and leadership of the family members of victims.

Developing an East African solidarity network

Heads of state in the region are fond of duplicating one another’s tactics. One flips the switch on social media, and the other turns it off the following month. Disappearances are an extreme form of repressing dissent, but rulers in the region have seen how effectively it silences their societies.

Without maintaining a grassroots East African network that is at least competitive with the amount of correspondence and cooperation the political elites are enjoying among themselves, residents of the region are doomed to an ever-shrinking civic space for the foreseeable future.

“East Africans need to collaborate at the regional level to ensure that the various treaties and conventions related to human rights are upheld,” Otieno said, noting that demonstrations in 30 towns across Kenya enabled police to apprehend another suspect of the murders who was still at large following the discovery of the bodies. With broader cooperation, greater achievements could be made. “In countries where public gatherings are impossible, we can use judicial activism and target specific leaders with cases in court.”

Rwanda and Burundi are particularly dangerous countries for those struggling to end state-sponsored injustices. Finding a dead person in the street or at the edge of a body of water is an increasingly normal occurrence.

Many of the Rwandans and Burundians who have spoken out in recent history are now exiled and largely carry out their own struggles with few external allies. Nininahazwe described recently leaving Burundi “clandestinely, since everything was set up for my elimination.” Other activists in the largely French-speaking areas of East Africa declined to comment for this article, citing possible repercussions.

Something must be done to overcome this climate of fear. Lack of engagement with regional neighbors may breed an even worse degree of insecurity in the long term. Resistance to the regional oligarchy can only be carried out by an East African community united amidst its diversity.

In terms of tactical approaches, the consensus in East Africa seems to be that vigils, while a starting point, are far from a sufficient answer to the atrocities perpetuated by death squads and a culture of impunity in the various nations of East Africa. Such acts of solidarity should serve only as catalysts for much more organized cross-border strategies.

IJM staff member Marian Bogere said they organized the vigil for their colleague to “tell Kenya that we care, that we feel their pain with them, that we care about human rights.” Such emotions are a fertile seedbed for an East African alliance against extra-judicial killings.

“We want this to be a watershed moment,” IJM field office director Claire Wilkinson told the press. “We want this to be the turning point for police reform and for police accountability in Kenya.”

Phil Wilmot is husband to Suzan Abong Wilmot. Together, they co-founded Solidarity Uganda with a group of Ugandan activists. The organization aims to train social change and environmental advocacy groups throughout Uganda in the skills, methods, and concepts of nonviolence. Phil and Suzan reside in Lira, Uganda with their daughter Aceng Nadia.