by Ken Butigan

I raise my hand in peace

I never bow to the laws of the thought police

I take a holy vow

To never kill again

To never kill again.

–Neil Young, “Living with War”

How can we tell the story of the nonviolent life? Gandhi did this by turning his life story into a series of pedagogical prompts for would-be satyagrahis in An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. In The Long Loneliness Dorothy Day chronicled her search for God that led her to a life of solidarity with the poor and nonviolent resistance. Civil Rights veteran and member of Congress John Lewis detailed his formation as an organizer in Walking with the Wind, and Grace Lee Boggs recounted her transformative journey as an organizer for racial justice in the 1930s to contemporary Detroit in Living for Change. John Dear’s recent autobiography, A Persistent Peace, unpacked his first 30 years as a tireless advocate for a better world.

There have been efforts recently to get major bookstores to set aside a section on peace and nonviolence, the way many have shelves devoted to war and military history. If this ever takes off, it will need a subsection featuring the autobiographies of nonviolent change agents, including these and many others volumes. I would hope though that the selections would broaden out from political activism to include accounts of people from many contexts and fields who have been contributing to the trans-historical process of building a more nonviolent world. Nonviolent transformation is not limited to picket lines and civil disobedience, and part of our job is to widen the aperture beyond a narrow sliver of the metamorphic bandwidth.

With an expanded notion of the nonviolent change agent, one obvious realm to scour is music. Musicians have been central catalysts for social transformation in innumerable ways throughout history, including as part of the waves of social movements over the past century down to the present moment. The Peace and Nonviolence section at Barnes and Noble will be a ripe spot for memoirs of musicians who have contributed to changing the world by creating socially conscious music and by being willing to “stand and be counted,” the title of a book written by singer-songwriter David Crosby on this subject.

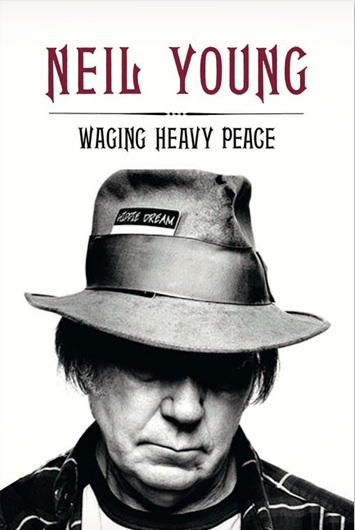

One volume I would nominate for stocking on these new shelves is Waging Heavy Peace: A Hippie Dream, the book that Crosby’s sometime bandmate Neil Young has just published.

Young has accumulated a patchwork of peace and justice cred across his career. From “Ohio” (a lamentation on the killing of four students protesting the Vietnam War at Kent State University) to “Southern Man” (calling out racist attitudes and actions); from “Mother Nature on the Run” (a cry of the heart about environmental destruction) to his recent “Love and War.” Nothing, though, beats his majestic 2006 album, Living with War, that eschewed subtlety and went instead for raved-up rock to prophetically denounce the U.S. war in Iraq, including the lies the Bush administration used to sell the invasion.

But this is only part of the reason I would recommend this book for the Peace and Nonviolence bookshelves at your local chain. Most of all, it is a compelling tapestry depicting a life searching for truth, with all of its fits and starts, chaos and composure. The book does not so much explore these themes as embody this life and the circuitous road it has fashioned along the way. Whether Young thought of it this way or not, for me Waging Heavy Peace is a manifestation of the nonviolent life itself in all of its ragged glory — not as a set of principles adhered to but as an attempt to meet the challenges that existence throws in one’s way with integrity and persistence, but also a certain wide-eyed innocence that is not dimmed after many decades of the rock-and-roll roller coaster.

To get at this Young does not produce a standard autobiography, where the author recounts the milestones of her or his life in more or less chronological fashion. While there are spangled flashes from nearly a half-century of stardom strewn across this 500-page volume, there is rarely any build-up to them. Almost as soon as they arrive they seem to dangle in mid-air without resolution, then give way to something else emanating from the musician’s sprawling space-time continuum.

Young is going for something more than a typical chronicle here. He assumes that whoever is willing to shell out 30 bucks for his plump book knows the basics already, or, if they don’t, can get the gist on Wikipedia. Rather than artfully plotting his life journey, he’s opted for an anti-memoir, or maybe more accurately a memoir from a parallel Neil universe, one that loops above and below — and around and through — whatever straightforward narratives are out there. His methodology? Trusting whatever comes up in the moment and then faithfully following its shiny thread until it coils off somewhere else.

This strategy, though it can feel capricious and arbitrary to the unsuspecting reader, is nothing new for Young. It’s the way he has lived his life, so it probably seemed the most appropriate approach to telling it.

This tack — a stream of vignettes, images, feelings, memories and prosaic ruminations appearing and dissolving, with the reader being yanked through a time-hole from 2010 to 1962 to 1978 to 1953 to 2009 — is improvisational but, in the end, not slapdash. It makes the entire book, not an account of a life, but a waking dream revealing this life in a way that no conventional narrative could justly do.

Waging Heavy Peace is a dream from start to finish, as its subtitle underscores. It does not simulate a dream (like one of James Joyce’s night-journeys or even the picaresque time-travel of Billy Pilgrim in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five). It is a dream. This dream, though, isn’t Freudian (unraveling wish-fulfillment or signaling the return of the repressed) or Jungian (saturated with archetypal meaning). It is, one might say, Youngian, an ocean of words as the rocker attempts to transcribe, moment-to-moment, the nonstop preoccupations of his waking life — his thoughts and memories, his longings and obsessions over the course of about a year beginning in 2011.

This, as it turns out, is also when he’s decided to get clean and sober. He finds it hard to write new songs without weed or alcohol through much of this period, though toward the end of the book he starts to warm up creatively as potential lyrics nudge their way to the surface even without his reliable, long-time aids. While songwriting eludes him for much of this time, Young’s creativity nonetheless flows on as he pours himself into his unfolding dream-book.

A tangle of obsessions weave through the book, and for the first 50 pages I was left thinking that his chief motivation in writing it was to advertise a new and improved digital music system (named PureTone and then, later, Pono) into which Young has poured himself and his resources. This obsessive quality extends to Lionel trains (he’s a part owner in the company), rebuilding old cars, creating something called the Lincvolt (which he sees as the electric car of the future) and renovating houses. There is something unnerving about these relentless fixations, though they speak to a deep drive to make things better.

More illuminating is how this dream-book is woven throughout with a series of other, floating books, what might be called Neil’s Book of Gratitude, Book of Mourning, and Book of Changes.

The text is regularly punctuated with heart-felt expressions of thankfulness for those who gave of themselves along the way: “Thanks, Ben!” “Thanks Pegi!” Unlike some memoirs, the point of this book is not to settle scores. He even thanks (and excuses) David Geffen, the Hollywood mogul who once sued Young for delivering a record “that was uncharacteristic of Neil Young.”

But this is also a chronicle of losses. Many of his closest companions have passed through. The book is a checkered meditation on death. Sometimes such a sustained reflection can lead to a sense futility and nihilism. Here it seems to have nurtured empathy.

And then there is the Book of Changes. Like the original — the I Ching — there is a relentless metamorphosis to Young’s life, with decisions made quickly that send him south where, moments before, he was cruising north. His resume is the most obvious indicator of this, sprinkled with the Squires, Minah Birds, Buffalo Springfield, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, the International Harvesters, endlessly recurring runs with Crazy Horse, stints with Devo and Pearl Jam, and tours all by himself. Throughout this book he testifies to a muse that keeps him from getting too comfortable and prods him further and beyond.

On February 4, 1968, I attended a concert at the Saint Martin’s College Pavilion in Lacey, Wash. I was 14 and I came to hear the Beach Boys, but I was bowled over by Buffalo Springfield, who opened for the then-more famous band. What I remember most was the ecstatic energy that Young and Stephen Stills generated, the sheer infectious joy as their fingers flew over the strings of their guitars and, with the fringe of their white Buffalo Bill coats flying in every direction, laughing and bouncing as their music broke over us.

Now, all these years later, it is possible to detect the reverberations of that happiness cascading down the decades, even with all the weather-beaten turns and struggles. The book’s title comes from an off-handed remark when the singer says he’s going to “wage heavy peace” against Apple (Pono delivers far more of the aural depth of digital music than iTunes, he says). But it aptly captures the entirety of this journey. Like most lives, Young’s has had its share of woundedness. But he’s taken to it with gusto and with “heavy peace”: the kind of infectious, if now tempered, joy that I glimpsed in 1968 and that has seemed to keep him moving relentlessly through the nightmares — and dreams — of this life.