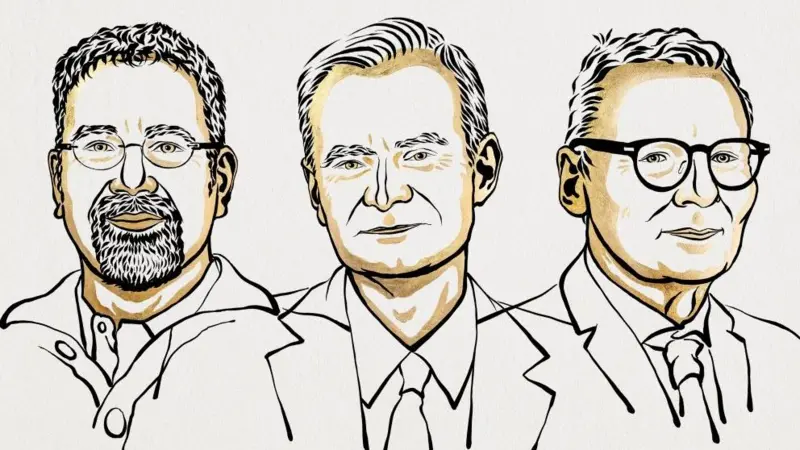

Three were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for their research on global inequality: Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, both from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and James Robinson, from the University of Chicago, shared this year’s prize for explaining differences in prosperity between countries.

They received the award for their work on prosperity differences between countries and for their research on how institutions affect prosperity, using both theory and data to better explain inequality between countries.

“Reducing the huge income differences between countries is one of the greatest challenges of our time,” Jakob Svensson, chairman of the Nobel Economics Prize Committee, said in a statement. “The laureates have demonstrated the importance of social institutions in achieving this.”

Their research has gone so far as to show that the institutions that were put in place during European colonization have helped shape the economic performance of the countries that were colonized since then.

“Leaving aside the question of whether colonialism is good or bad, we observe that different colonial strategies have led to different institutional models that have persisted over time,” Acemoglu said at a press conference following the announcement of the award. His findings suggest that inclusive institutions tend to set countries on the path to long-term prosperity, while extractive ones – designed to maintain the control of those in power – provide short-term gains for those in power but do not generate social prosperity.

“Broadly speaking, the work we’ve done favors democracy,” Acemoglu said. “But democracy is not a panacea.” Democracy can be difficult to implement, he noted, and there are avenues of growth for countries that are not democracies, such as rapidly harnessing a nation’s resources to accelerate economic progress. But he said “more authoritarian growth” tends to be more unstable and less innovative.

The three Nobel laureates found that colonization caused a major shift in global fortunes. Densely populated places at the time of colonization tended to be governed by authoritarian institutions, while sparsely populated ones were open to receiving more settlers and established a more inclusive, though not entirely democratic, form of government. Over time, this led to a reversal of fortunes: whereas the Aztec Empire was more populous and wealthier than North America at the time of the first European explorations, today the United States and Canada have surpassed Mexico in prosperity.

“This reversal of relative prosperity is historically unique,” the Nobel statement explained. “If we look at the parts of the globe that were not colonized, we find no reversal of fortune.”

The legacy is still visible today. As an example, Acemoglu and Robinson have pointed to the city of Nogales, located between Mexico and Arizona. Northern Nogales is more prosperous than the south, despite sharing culture and location. According to the economists, the differences are due to the institutions that govern the two halves of the city.

These economists have written books based on their research, including Why Countries Fail, by Acemoglu and Robinson, and Power and Progress, by Acemoglu and Johnson, published last year.

The Swedish academy noted that “the richest 20% of the world’s countries are 30 times richer than the poorest 20%. The income gap between the richest and poorest is also persistent; although poor countries have gained in wealth, they are not catching up with the most prosperous.”