Some of Spain’s hospitals and clinics have recently begun offering a new kind of public service. In an effort to defend the threatened health care system, thousands of doctors and their supporters have chosen to add civil disobedience to their practice.

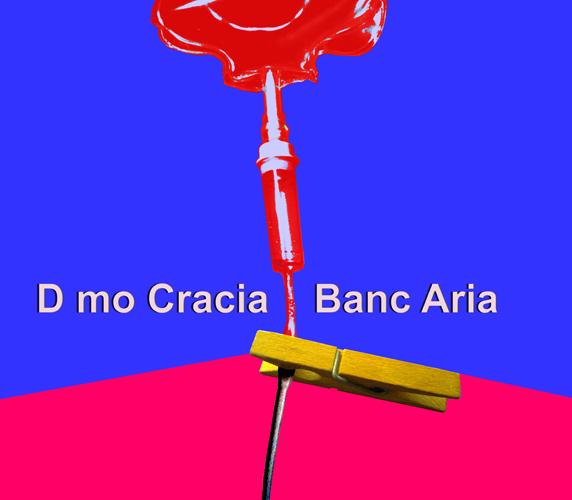

Last April, the Spanish government approved a Royal Decree — a norm comparable to a law but not approved by the Parliament — that changed the country’s health care policy. Previously, the public health care system covered all people in the country without exception, but the new norm withdrew coverage from illegal immigrants and Spanish citizens over the age of 26 who have not paid into the National Health Service — namely, housewives, students and others who have never worked on a contract. In June the government provided this second group, at least, the chance to have a health card, but since September 1 illegal immigrants in Spain have only been able to access the public health system in cases of emergency or by paying an expensive bill.

“This is not a cut, it’s a change to the system,” says Marta, a member of YES to Universal Health Care (Yo SÍ Sanidad Universal) who, like many Spanish activists, asked to be identified only by her first name. “It is the seed of the privatization of health.” YES to Universal Health Care started in April out of an assembly of people who worked with immigrants. It has two clear goals: making visible the consequences of the Royal Decree and overthrowing the new norm with civil disobedience.

The first step for YES to Universal Health Care was to develop manuals addressed to health care workers and patients explaining how to avoid the new norm through loopholes in the bureaucracy. Next, other collectives such as the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine and Doctors of the World joined the campaign, encouraging health workers to declare themselves conscientious objectors to the new norm. Within a few months, more than 2,000 doctors and other health care workers signed on as objectors to the Royal Decree, and even more have opted not to follow the norm.

“A lot of people without health cards are being treated by doctors who have not declared themselves as objectors, but who are avoiding the law,” says Irene, also a member of YES to Universal Health Care.

In several regions, the government threatened health care workers with legal reprisal if they don’t follow the law. But by June the health ministry budged by stating that the government would allow doctors to do “whatever they think is necessary with each patient.” It was the first victory of the campaign, but the goals of YES to Universal Health Care are much greater.

“We don’t want to create a parallel health system, looking for the doctors who are objectors to the law,” explains Marta. “We want to continue on as if the Royal Decree didn’t exist.”

To that end, the campaign’s next step was to promote the creation of support groups that would accompany people without a health card as they explain to doctors and other hospital workers how and why to avoid the law. In the past month, YES to Universal Health Care has held workshops, with the help of the 15M movement’s assemblies, in more than a dozen neighborhoods of Madrid. It also supported groups across the country in developing their own workshops and support groups.

Karlos Royo, of the 15M assembly in Madrid’s Malasaña neighborhood, is a member of one of the support groups. He began the group when he found out about the case of a neighbor with a kidney disease who, because she was an immigrant, was forced to stop taking her medication. “This is not just about helping the poor or the immigrants, it is about defending our public health care system,” Royo recently told two dozen people taking part in a workshop held in Chueca, another neighborhood in Madrid.

The job of the support groups is, in the first place, to probe the attitude of workers at a given health center toward the new norm, and then to spread the disobedience campaign by sharing information about how health care workers can treat people who don’t have a health card. “The first person the patient has to speak with is the administrative assistant,” explains Marta of YES to Universal Health Care. “If he doesn’t heed the patient, the support group intervenes.”

Several support groups in Madrid have had meetings with the directors of the health centers in their districts, who have agreed to make compromises to avoid the Royal Decree. “It is important to be insistent and show that we know what we’re talking about,” explains Marta, who pointed out that when patients ask for a meeting with doctors to talk about the issue, the workers in the health centers usually get excited about resisting.

Each day, more people are avoiding the Royal Decree, but for activists the next step is to overthrow it. At the moment, in regions like Andalusia, Canarias and the Basque Country, regional governments have rejected the new norm and have looked for ways to retain health care for all people. But the effort to bring a pulse back to the universal health care system as a whole continues.

“The movement is starting to walk,” says Irene. “But we can force the government to remove the Royal Decree if we apply more pressure in the streets.”

The original article by Ter Garcia was first published here in wagingnonviolence.org