Bulgaria, per tutti i morti di frontiera.

At about 12 o’clock, the number of the collective receives the signalation of the body of a 30-year-old Syrian boy, H., who died during a game attempt near route 79. We have the contact of a brother, who is in Turkey and communicates with us through a cousin who acts as an interpreter. They ask for help in managing the recovery, recognition and repatriation of the body; they send us the coordinates and we understand that the body is in the middle of a forest but close to a track: his companions probably left him there so that he could be easily reached. Over the next few hours, we figure out together how to move.

3 p.m., a local association we work with calls 112, the general emergency number, for the first time. They tell us that the case has been taken over and that the authorities have started a search. In the light of other similar incidents, we decide not to trust them and start thinking that we might need to set out.

4.46 p.m., we also call 112, to put pressure on them and make sure that there is indeed a search team on site: we decide to tell the operator that there is a person in critical condition lost in the woods and we give the precise coordinates. In response, he asks us his name and, even before information on his state of health, his nationality. It is a border area: probably, the answer to this question is crucial to understand what priority to give to the call and who to alert. When we say he is Syrian, the question automatically comes up: ‘How did he cross the border? Legally or illegally?”. We say we don’t know, we repeat that H. needs immediate help, he might be dead. The operator accepts our report and tells us that police and medical assistance have been alerted. We ask for an update, but they cannot call us back. We call back.

5.54 p.m., we call back. The operator asks if the emergency group has arrived on site, probably thinking that we are with H. We inform her that we are actually an hour and a half away, but that we can go there if necessary. She tells us that the border police ‘was there’ and that ‘everything will be OK if you called us’, but has no information about H’s fate. We ask her, again remembering the false information in other cases, how she can be sure that a patrol has been there; only at this point she does call the border police. “It was my mistake,” she tells us resuming the call: the officers have not found him, “but they are looking for him”. To our ears this sounds like a confirmation that no patrol went out looking for him. The operator ends the call with: ‘If you can, go to this place, [to] these GPS coordinates, because they couldn’t find this person yet. If you have any information call us again’. Strong of this green light and pissed off at having to make up for the police’s shortcomings, we go.

At 6.30 p.m., we leave Harmanli, calling 112 at regular intervals along the way: great indifference emerges, which becomes at times outraged at our insistence: ‘So what do you want now? We don’t give information, we have the signal, police is informed’. We say we are on our way: ‘OK’.

8.24 p.m., we park the car along a country road in the middle of the forest. We start walking towards the coordinates as the sun behind us begins to set. We call 112, informing them that we see no police patrols around, despite all the phantom searches that they say have already begun. We are told that the police have been to the coordinates we have given and have found no one; the events of the following hours will prove this information to be false.

“I talked with Border Police, today they have been in this place searching for this guy, they haven’t found anybody, so”.

“So? […] What are they going to do?”

“What do you want from us [annoyed]? They haven’t found anyone […]”

“They can keep searching.”

“[aggressive] They haven’t found anybody on this place. What do you want from us? […] On this location there is no one. […] You give the location and there is no one on this location’.

9.30 p.m., we arrive at the coordinates through a forest, where backpacks and empty bottles suggest the passage of people during game. H.’s body is there, not a metre ahead, not a metre behind. His fellow travellers, despite the situation of need that the route imposes, left his backpack, his phone and some medication close to him. It is evident that no police patrol was on the scene, probably none even left the station. We moved along a chain of lies. We call 112 again and the operator alerts the border police. This time, given the length of time we remain on the call waiting, it would seem she actually called.

9.52 p.m., no one in sight. We call back insisting to know where the emergency unit is, as we fear once again the absolute disinterest of those in charge. We are answered: ‘Police crew is on another case, when they finish the case they will come to you. […] There is too many cases for police, they have only a few cars’. Given the number of checkpoints and police cars we passed along route 79 and the accounts of its continuous, capillar and violent interventions in ‘protection’ of the EU’s eastern borders, it does not seem to us that the police have no means. Evidently, again, it is a question of the priority of cases and the ends of them: they move to control and pushback, not to rescue. We insist, they ask about us and the car:

“How many people are you?”

‘Three people’

“Only women?”

“Yes…”

“Have patience and stay there, they will come’.

We have the strong perception that the fact that we are only girls will speed up the intervention and that certainly no one will move for H.: the pull factor for police intervention has become us, the Italian girls in the middle of the woods to be rescued. We express among ourselves the need to make it clear, in case the police arrive, that the priority for us is the recovery of H.’s body. We also hear from our companions who stayed at home: faced with yet another stalemate update, three of them decide to leave Harmanli and join us at the coordinates; for them, it will be an hour and a half in a van: along the way, they will be stopped three times at roadblocks, vans being one of the smugglers’ most used means for moving migrants towards Sofia.

10 p.m., we continue with the pressure calls to 112. It is a woman who answers: her voice sounds worried. Even in the violence of the situation, we register how gender socialisation is decisive with respect to the caring posture. She connects with the border police: ‘Police is coming to you in 5…2 minutes’, she tells us in an attempt to reassure us. Unfortunately, we are well aware that police practices are far away from those of care and we have no illusions: the wait will continue. As expected, an hour later no one has yet arrived. On the umpteenth call, the receptionist asks us about the morphology of the area around us. This request confirms what we already knew: the police have never arrived there.

11.45 p.m., lights illuminate the field where we have been sitting for hours near H’s body. It is a border police car, with a mixed patrol of normal police and border police on it. No sign of an ambulance, medical personnel or forensic police. They ask us to show them the body. They absent-mindedly shine a light on it, make a few calls to the station and come back to us: they ask how we found out about the case and why we are there. We tell them again that it was a 112 operator who suggested this to us: this allows us to justify our presence in the border area, next to a corpse, and avoid accusations of smuggling.

11.57 p.m., they offer to take us back to our car, not even 10 minutes after arriving. We ask what will happen to H.’s body and an agent replies that a special emergency unit will arrive. We express our willingness to wait for its arrival, we want to get as much information as possible to give to the family, and we are worried that if we leave the camp, the patrol will also leave the body. Stranger still, and perhaps unprepared for our presence and insistence, they try to convince us to go, illustrating a farcical series of dangers ranging from the fact that it is an interdicted border area to the presence of dangerous migrants and giant hornets. Basically, we perceive that they have no valid reason to prevent us from staying.

When Harmanli’s group arrives close to us, the police hear them coming before they see them and think they are a group of migrants; to this stimulus, they respond with the readiness they have never shown to our urging. He sprints towards them with his gun and truncheon and his torches pointed towards the woods. He finds them, but their skin colour is on the spectrum of legitimacy. It’s OK, they can get to us. Of the patrol of six policemen, three drive away, three actually stop for the night; we wonder if it would have gone the same way if we with our white, European eyes had not been there. The standoff continues, essentially, until morning: the situation is surreal, with us lying a few metres away from the police and H’s body. The image that emerges speaks of the negligence of institutions, of the hierarchy of lives that the border creates, and of the systematic abandonment of the bodies that move around it, if not for their possible rejection.

8 o’clock in the morning, the indifference continues even when the forensic team arrives, moving hastily and summarily around H.’s body, wearing jeans and taking a few symbolic photographs. The whole thing lasts no more than 30 minutes, at the end of which the body leaves in the border police car, without any communication about its direction or fate. After the usual strategy of insistence, we learn that he will be taken to the Burgas morgue, but they have nothing to tell us about what will happen next: the hypothesis of repatriation of the body or a possible funeral does not even seem to touch their thoughts. Once again, their indifference towards H., a body deemed illegitimate that does not even deserve a burial, becomes apparent. Death is normalised in these border spaces and systemic indifference becomes a weapon, together with violence against bodies and rejections, to define who is entitled to a worthy life, or simply to a life.

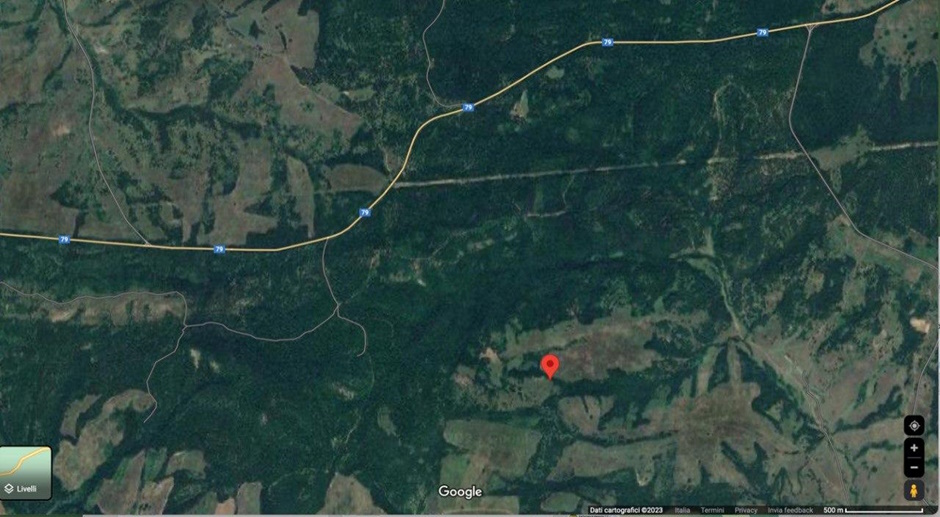

The location that was sent to us by family members and where we found the body. In yellow, Route 79, one of the roads used as a reference point by migrant people during the game

The location that was sent to us by family members and where we found the body. In yellow, Route 79, one of the roads used as a reference point by migrant people during the game