In the ideological struggle between rightists and leftists, the so-called welfare state has come to the fore, that is, the situation in which many countries on Earth live that are recognised for their democratic prerogatives, but in which there would not be levels of social inequality as pronounced as those in Chile and a good number of other countries. The examples of Sweden, Finland, Germany and other European nations are recurrent in all debates, with the exception of the United States, whose condition is not at all paradigmatic in light of its pronounced inequalities and high concentration of wealth.

Today, capitalism refers to the private ownership of the means of production and the subsidiarity practised by the states that apply it in accordance with their political constitutions and laws. But between one capitalist country and another there are often abysmal differences. It is true that socialism (or state capitalism) is on the verge of extinction, which gives many a reason to proclaim the definitive triumph of the free market and, incidentally, to proclaim the failure of those experiences in which the state was assigned the leading role in the economy.

But there is everything in the “vineyards” of capitalism. What happens in Denmark, as in Brazil, Argentina and Chile itself, is very different. Not to mention the enormous contrasts that exist between developed and third world countries; between the welfare standards of one and the other, taking into account the rights of workers, the incomes of their pensioners or the very cultural and educational expectations of their young people.

Worse, still, if their respective institutional models are compared. The differences in what happens, for example, with the suffrage of well-informed peoples and what results from the vote of those who maintain high levels of illiteracy with respect to those nations that are better informed and where there are acceptable levels of press freedom.

There is no doubt that those who take capitalism as their political, social and cultural paradigm have had to grudgingly accept their peoples’ demands for greater freedom and equality. Not without suffering many internal conflicts, such as those now taking place in France, Greece and other countries recognised for their good levels of equity, albeit with serious social backwardness. The capitalism of post-war European countries must necessarily acknowledge Social Democracy and Christian Democracy itself for having organised their economies with recognition of workers’ rights and for having put a stop to the concentration of wealth. Influenced, too, by the equality proclaimed by the countries of the East or behind the so-called Iron Curtain.

Otherwise, Nazism and Fascism would have left more substantial traces in the social and political organisation of nations that were just emerging from their enchantment with totalitarianism and its regimes of terror. However, the disciples of Hitler or Mussolini were politically relegated to a minimum, even if the latter have now regained positions that could shake the very foundations of European unity. The wisdom of an Adenauer, a Billy Brand or a De Gásperi was to build democracies that proposed decent levels of social justice, which today in Chile are considered dangerous for the objectives of economic growth, foreign investment and other aspirations of the Pinochettism so enthroned in the right-wing parties and which, by the way, accept the free and informed vote of the people with many qualms. Human rights are always considered as a pamphlet of the leftists.

Obviously, it is no longer possible to think either of the nationalisation of all productive assets, or of the privatisation or foreign ownership of all basic and strategic resources. But, of course, it is possible to conceive of an economic and social order in which trade union rights are fully protected and in which the state assumes ownership and exploitation of strategic resources such as copper, oil, lithium and others. In addition to consolidating pension, health and education systems that guarantee dignified access for the entire population. These aspirations are also a legacy of socialism and its various democratic and libertarian denominations.

The Latin American peoples have long been making a synthesis between the predicaments of capitalism and socialism, recognising private initiative in many areas, but also demanding that their states manage certain ambits of the economy in which profit would be abusive and would risk losing our national sovereignty.

It is very curious that, these days, right-wing analysts are boasting about the merits of a capitalism that in practice has been humanised or domesticated by avant-garde ideas. In the same way that political or electoral democracy is not the child of capitalism or of the right. If we consider its recent manifestations in coups d’état and civil-military dictatorships. As well as the horrors spread throughout the continent to impose their hegemony.

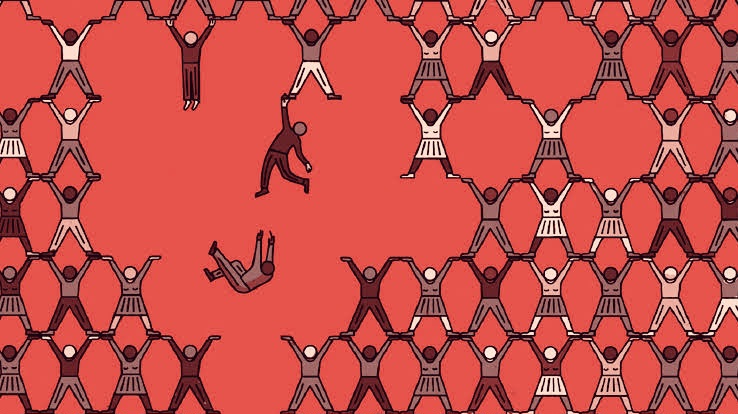

Unfortunately, it has become customary that when governments propose to mitigate social injustices, prohibit the extreme concentration of wealth and distribute income more equitably, conspiracies invariably emerge, along with the usual barracks coups and de facto regimes. Indeed, despite the mistakes and horrors also committed by left-wing administrations, what cannot be doubted is that it is from these positions that social justice is best promoted, both in government and in opposition. This is precisely what has led to the existence of the welfare states that are nowadays alluded to and recognised as a great achievement in the search for political and social harmony.