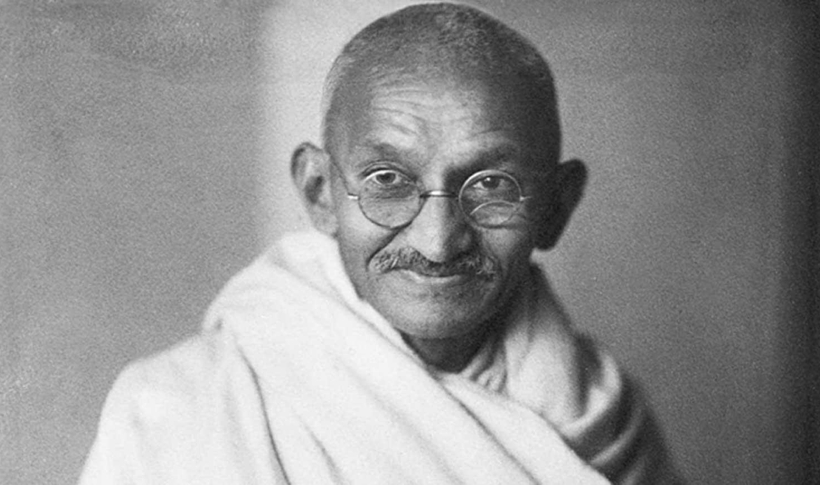

Mahatma Gandhi’s thought and political action are part of the movement for the revival of Hinduism that took place in India from the last years of the nineteenth century until the first half of the twentieth century, following the strong impact that Western culture had caused on Indian civilization during two centuries of widespread British colonization.

Gandhi represents the highest expression of the Indian cultural movement that aimed at the full reaffirmation of the essential values of the Hindu tradition against the slavish imitation of Western ideas that had been developing along with the triumphant image of British colonialism, industrial society, opulence, and nascent consumerism. The Hindu tradition, to which Gandhi drew on, rests on a wealth of lofty knowledge “heard” from the ancient r.s.i or sages and transcribed in the Vedas, Upanishads, and Puranas, giving us ante-litteram lessons in degrowth, nonviolence, and deep ecological lifestyle in connection with the Whole.

This is what we talk about with Gloria Germani, an eco-philosopher who has always been engaged in dialogue between West and East, a student of philosopher Serge Latouche, Swedish ecologist Helena Norberg Hodge and journalist Tiziano Terzani, of whose thought she is among the foremost experts. Active in deep ecology movements, the Network for Deep Ecology, Navdanya International and the Association for Degrowth, she is a practitioner of Advaita Vedanta (Way of Non-duality), the best known of all the Vedānta schools of Hinduism. In 2002 she wrote the book Madre Teresa e Gandhi (Mother Teresa and Gandhi) with a preface by Terzani, who, having taken a strong interest in Gandhi in the last years of his life,(1) said, “Germani’s book gives us one of the best interpretations of Gandhi that I have happened to read.”

Many Westerners like to see Gandhi as an “Indian sui generis” closer to Western and Christian culture than Eastern culture. There is also the legend that Gandhi did not convert to Christianity only because the two World Wars had originated from traditionally Christian powers. What are your thoughts on this? Is Gandhi a “sui generis” (unique) philosopher or an integral part of Hindu culture?

I have studied and pondered Gandhi for a long time, and I maintain that his thought is situated within Indian culture, the culture of his fathers and people, and cannot be understood without keeping this view in mind. Of course, in his life, Gandhi was constantly in contact with Western culture: in London where he studied law, in South Africa where he began his nonviolent struggle against the British regime, and of course in India. Because of this, he devoted himself to a careful analysis of antagonistic culture through the study of many Western writers. The authors who struck him most positively were Tolstoy, Ruskin, Mazzini, Thoreau, and he always devoted himself to meditating on the scriptures of the great religions: the Gospels, but also the Koran and the Avesta (translator’s note: the Avesta is the sacred writings of Zoroastrianism – 4th century AD), moved by a spirit of openness and sincere search for the truths contained in them. Yet Gandhi never ceased to consider himself a Hindu sanatani, that is, an orthodox Hindu, and made it clear that his doctrines of ahimsa (nonviolence) and satyagraha (the power of truth, adherence, agraha, to the truth, satya) were nothing but the restatement of Hindu concepts. “I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and nonviolence are as old as the mountains” (2); “Although I am an admirer of certain aspects of Christian doctrine – he wrote – I cannot identify with Christianity. Hinduism, as I know it, entirely satisfies my soul, occupies my whole being. ” (3)

Albert Einstein wrote of the Mahatma, “Future generations will find it hard to believe that such a man as he really walked this earth.” In the face of such greatness, most Westerners have instead sought to include him in supposed Christian and Western superiority. Indeed, many of our own pacifists and intellectuals make a great mistake: that of studying Gandhi without knowing practically anything about Hindu culture and the radically different worldview from ours that it underlies. Indeed, I believe that behind the legend you refer to are two great myths of the West: that Christianity is the pinnacle of all religions (for which the others serve as a preparation); and that the West is the superior civilization among them all. These are precisely myths without real foundation, but with dangerous consequences.

Can you tell us about nonviolence philosophy and Satyagraha as a tool of political struggle and liberation?

To understand Gandhi, as I said, we need to be aware of Indian thought. At the core of Hindu philosophy is the certainty that all life is One; not only that of human beings, but of all living organisms: animal, plant, mineral. This also means that there is no clear separation between what is mind and what is matter (or in more Western terms between spirit and body). The philosophy of India is in fact the Advaita philosophy of non-duality that runs through Indian thought from its origins in the Upanishads (at least 8th century B.C.) in an unbroken chain to the present day. The philosophy of non-duality is reflected in the certainty in the unity and sacredness of all that lives, without exception. From this certainty that the world and humanity are an interconnected and indivisible whole derives the great truth of nonviolence. Even the conception of man is essentially different from ours; each human being is essentially good and potentially divine (an avatar, a manifestation of the divine on Earth); if he/she has moments of deviation he/she can be redeemed through contact and relationship with others.

This is the core of the millennial thought that Gandhi takes up and summarizes in the neologism Satyagraha, “the force of truth.” For as he repeated so many times, nonviolence and the force of truth are one and the same. It is evident that Mahatma could not have had millions and millions of followers if this thought was not ingrained in the culture and people of India. Through the power of truth and nonviolence, the adversary or the enemy is not converted through imposed

violence, and thus [through] wounds, wars and bombs (nowadays moreover launched from sidereal distances with drones). The opponent, on the contrary, is converted simply because he or she is exposed to the sight of another’s suffering. The supposed enemy will understand the claims through the recognition of common humanity, through a movement of ennobling one’s own feelings. On the other hand, the nonviolent fighter is willing to defend the truth with majestic courage because – since everything is interconnected – the deviation of some to violence, abuse, greed for power and possession, violates the human essence and will have dramatic repercussions on other humans, society and even the ecosphere.

There is one more very important point. To be a nonviolent fighter, it is not enough to take university courses or training workshops, but one must undertake long and complex work. One must be able to purify one’s ego through the abandonment of self-interest and the desire for self-assertion and appropriation. Work on oneself must precede any nonviolent struggle. At the political level, too, Gandhi was convinced that independence, the autonomy of India – swaraj – must be the result of achieving personal swaraj, self-mastery, mastery over the passions, to bring out the nobler and higher sides of the personality. For this, he constantly referred to the five precepts or yamas common to Hinduism, yoga, Buddhism and Jainism. Gandhi himself said, “Those who seek truth should undergo preliminary discipline and take a vow of sincerity, purity, nonviolence, poverty and non-possession. Until you undergo the five vows, you cannot embark on any quest. Precisely because nowadays everyone claims the right to conscience without submitting to any discipline of any kind, so much falsehood is dispensed to a confused world. All I can deliver to you in all humility is that truth cannot be found except by someone who has attained a great sense of humility. If you want to swim in the lap of the ocean of truth, you must reduce yourself to a zero. More than this I do not know, and cannot say. “(4) In another passage in which he comments on the essence of the most important text in Hindu culture, the Bhagavadgita,

Gandhi says, “I have come to the conclusion that the Gita (translator’s note: the Gita is a 700-verse Hindu scripture; it is considered one of the holy scriptures of Hinduism.) was composed to teach this one Truth: we can adhere to the Truth to the extent that we free ourselves from our attachment to the ego. “(5)

Marco Ferrini, an Italian Hare Krishna master and Indovedic philosopher, has called Gandhi “the most political of spirituals and the most spiritual of politicians.” What do you think?

This definition by Ferrini is certainly fitting and helps us to focus on some neuralgic points. First, that the distinction between spirit and matter/concrete reality to which politics would pertain is not a universal distinction. As I said, Eastern philosophy never conceived of the separation of mind and matter, and we should point out that even physics has for 100 years been teaching us that such a distinction is false. We have made the separation of religion and secularism (spirit-matter) one of the cornerstones of modernity, but – given the enormous current crisis, ecological, sociological, and existential – I think we will have to revisit it. In fact, there is a lot of talk today that we should re-sacralize the world. The separation of spirit and matter has a lot to do with Western Judeo-Christian religion, its dogmas and hierarchies that have no equivalent in other cultural contexts. Gandhi argued that “those who claim that religion has nothing to do with politics have no knowledge of religion. “(6) In fact, the Hindu view teaches us that everything is One, everything is sacred, as we said at the beginning, beyond the illusory appearance of multiplicity and everyday becoming, which are in fact considered maya (translator’s note: maya means illusion).

Gandhi writes in his Autobiography, “To see face to face the universal and omnipresent spirit of truth, one must be able to love the lowest of created beings as oneself. And a man who aspires to this cannot afford to alienate himself from any field of human activity. That is why my aspiration for Truth led me to politics; and I can say without any hesitation, though with absolute humility, that those who claim that religion has nothing to do with politics do not know what religion means. Identification with every living being is impossible without self-purification; without self-purification, observance of the law of ahimsa (translator’s note: ahimsa is respect of and nonviolence towards all living beings) remains an empty dream. “(7)

I would still like to distinguish the religion to which the Mahatma refers from ours. The God of whom Gandhi speaks has nothing to do with a God-person, a creating God. This dualistic conception of a transcendent God is foreign to Eastern thought. Gandhi says, “I recognize no other God except the God who is in the hearts of the silent multitudes. They do not recognize his presence. I do. I worship that God who is Truth or the Truth who is God through the service of these multitudes. “(8) And in another passage, “In order to conform to such a religious conception one must devote one’s whole being to service and action. One cannot tap into, realize the truth, without immersing oneself, without identifying oneself with the infinite ocean of life. I cannot exempt myself from serving society nor could I find happiness in anything else. And one must serve in every way, in every form. Nothing is too high, nor too lowly; everything is one and multiplicity is an appearance. “(9)

Gandhi was undoubtedly an anti-colonial leader. In what does his critique of colonialism consist? Is it something broader than a critique of British rule?

Absolutely. Gandhi reiterated this many times. His struggle was not against the British but against the kind of civilization that the British had embraced and brought to India. Gandhi wrote, “There is no insurmountable barrier between East and West, between white man and yellow man, rather there is a modern civilization that is completely materialistic and because of that has made people lose the sense of the true purpose of living.” His assessment of Christianity is also very clear and in 1920 he wrote, “The religion of the West, Christianity, has exhausted its function because it does not have the courage to combat violence with love. The ethical values of Christianity have become abstract truths that have no influence on the lives of individuals, much less [on the lives] of peoples. “(10) The Mahatma touches on a second decisive point: “Modern civilization is a civilization in name only; under its action the European states are degrading and ruining themselves day by day.” And he concludes, “For those who are intoxicated by it, the only god is money and they wish to turn the whole world into a huge marketplace for their goods. “(11).- Truly prescient words when we think that they were spoken 100 years ago. When he was still in South Africa and, as a lawyer, defending the Indian community against the abuses of the British colonial government, in 1909, Gandhi wrote his first book – Hind Swaraj – where all his positions are condensed: up to the end, he said there was not a single line he would not subscribe to again.(12) And an extraordinary text reissued in Italian by the Gandhi Center as I Teach You the Evils of Modern Civilization. The truly focal question that Gandhi asks and with which he titles Chapter XII is: What then is true civilization? Can we consider civilization as being the faster people move, or how they dress? He answers, “Civilization is that form of conduct which shows man the path of duty and the observance of morality. To observe morality is to gain mastery over our minds and passions. If this definition is correct then India, as many writers have shown, has nothing to learn from anyone […]. We realize that our mind is a restless bird. The more it gets, the more it wants, the more it still remains unsatisfied. Our ancestors, therefore, put a limit on our indulgences. They saw that happiness was largely a mental condition. A man is not necessarily happy if he is rich or unhappy if he is poor. Observing all this our forefathers deterred us from lusts and pleasures […] And here Gandhi makes the decisive observation – It was not a question of not knowing how to invent machines, but our fathers knew that if we devoted our hearts to such things, we would be enslaved by them and lose our moral fiber. They therefore, after dutiful reflection, decided that we would do only what we could do and with our own hands and feet. They saw that our true happiness and well-being consisted in the proper use of our hands and feet. “(13) Thus the very assumptions of the supposedly superior civilization or Progress fall away. These are issues that would be very timely to revisit thoroughly today. To return to nonviolence and the force of truth, the greatest scholar of Hinduism – in my opinion – the German Herich Zimmer has argued, “The program of satyagraha (the force of truth) constitutes a serious, modern and potentially very powerful experiment of the ancient Hindu science to transcend the lower powers and to enter that of the higher powers. Gandhi confronted the non-sincerity (asatya) of Britain with the sincerity (satya) of India, the British policy of expedients with the sacred Hindu dharma. “(14)

1 Cf. In particular, the last two chapters of Lettere contro la Guerra (letters against the war), Longanesi 2002 and the six final chapters of La Fine è il mio Inizio (the End is my Beginning), Longanesi 2006 are dedicated to the complete approach to the Gandhian vision. See Gloria Germani, Tiziano Terzani, La Forza della verità (The power of truth), conclusion: “Dal capitalismo a Gandhi “(From Capitalism to Gandhi), Punto di Incontro, Vicenza, 2015

2 M.Gandhi, Antiche come le Montagne (Ancient as the Mountains), Mondadori, 1987.

3 M. Gandhi, Christian Mission July 28, 1928. see my Madre Teresa i Gandhi, L’etica in Azione

Mother Teresa and Gandhi, Ethics in Action, Mimesis, 2016, p. 61ff. 4 M.K. Gandhi, Young India of December 31, 1931.

5 M.K. Gandhi, Gandhi commenta la Bhagavad Gita (Gandhi comments on the Bhagavad Gita), Edizioni Mediterranee, 2012, p. 43.

6 M. K. Gandhi, An autobiography or the history of my experiments with truth, transl. it. My Life for Liberty, Newton Compton, p. 453, and M. K. Gandhi, Theory and practice of non-violence, cit., 31.

7 Gandhi, An autobiography or the history of my experiments with truth, trans. It. La mia vita per la libertà (My Life for Liberty), Newton Compton, p. 453 and M.K. Gandhi, Teoria e pratica della non violenza (Theory and practice of non-violence), cit., p. 31.

8 M.K. Gandhi, The Essence of Hinduism, p. 65 (Harijan, March 11, 1939).

9 G. Borsa,Gandhi. La vita di un profeta del nostro tempo (Gandhi. The life of a prophet of our time), Bompiani, 1983, cit., p. 193-4.

10 M. K. Gandhi, Appeal to Lord Chelmsford, 20 March 1919 (from M. K. Gandhi, Speeches and Writings, An Omnibus Edition, Madras, Natesan, p. 467). See G. Borsa, Gandhi, la vita di un profeta del nostro tempo (Gandhi, the life of a prophet of our time), Milano, Bompiani, 1983, p. 176.

11 Gandhi, Vi spiego i mali della società moderna (I explain the evils of modern society), cit., p. 50 and p. 57 (my italics).

12 Cfr. R. Altieri, Hind Swaraj compie cento anni (Hind Swaraj celebrates one hundred years), introduction to M. K. Gandhi, Vi spiego i mali della società moderna (I explain the evils of modern society, – Hind Swaraj, cit., p. 7.

13 M.K. Gandhi, Vi spiego i mali della società moderna (I explain the evils of modern society, cit., pp. 75-76 (italics mine).

14 H. Zimmer, Filosofie e religioni dell’India ( Philosophies and religions of India), cit., p. 155.