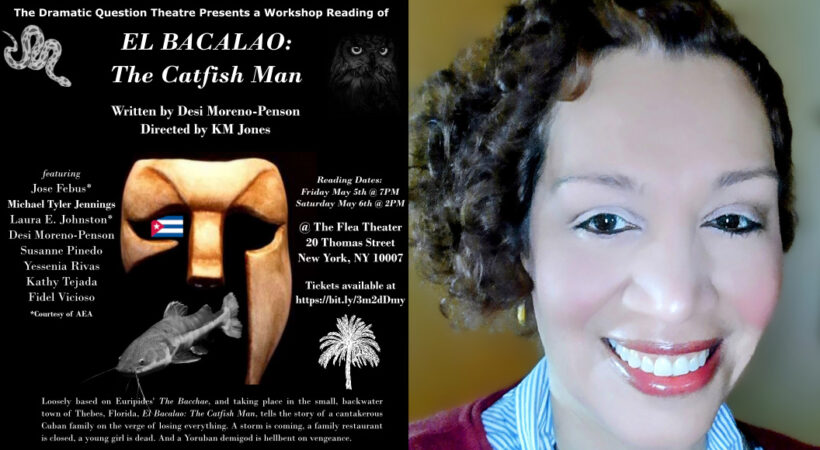

I love the restaurant Cuchifritos. Located in Spanish Harlem, Washington Heights, The Bronx, our famous Cuchifritos offers habichuela (beans), pernil (roast pork), mangú (a Dominican dish) or mofongo (a Puerto Rican dish), and of course, the famous bacalao, the dried, salted, cod fish that reminded me of my mother’s cooking for Good Friday when we only ate fish. In a similar Cuban restaurant in Thebes, Florida, Desi Moreno Penson sets her new play, El Bacalao, The Catfish Man, playing at The Flea. Based on The Bacchae by Euripides, Desi Moreno puts Pentecostal Cuban characters before their African religious beliefs. The characters, the cooks, and the restaurant owners have lost the sense of taste when a semi-African God appears to be their savior.

When I was reading the play, I wanted to taste bacalao, which is the same temptation for all the characters. I soaked the fish overnight. The following day, I peeled the potatoes, cut them, and added them to the pan along with onions, peppers, tomatoes, and cilantro, where the bacalao had already been cooking. The dish for my lunch was a contrast of the white rice against the reddish tomatoes, translucent onions, and brown, pinkish flesh of the fish with dots of green. I dipped a spoon in it. A taste. The flavors hit my palate, and I know I’m saved.

I was then interested in learning more about the process and inspiration behind El Bacalao. I asked Desi Moreno-Penson a few questions about her play and got some insight.

JS: “El Bacalao.” What a perfect title. How did you decide to call your play that?

DMP: I’m so glad you like it! As a playwright, I try to come up with interesting, thought-provoking titles that will catch people’s attention. I came upon this particular one as a more Latinx-rendered play on the original title of The Bacchae—El Bacalao! When I first told my partner, Anthony, that I was writing the play and I mentioned the title, he immediately started laughing. That’s when I knew I had a good one on my hands.

JS: The play is inspired by Euripides’ The Bacchae. Why is Euripides still valid today?

DMP: Euripides and Greek Drama as a whole continues to do something most contemporary plays aspire to; put a mirror up to an audience and show us who we really are. These are works that brutally expose the pretensions in human claims to control and certainty. We all want to believe we have control over our lives and our destinies. Greek Drama shows us that we’re just fooling ourselves. These are plays that espouse the universal themes of love, family, community, spirituality, and unapologetically show us the tragic outcomes of what can happen if we take these for granted, if we’re too full of ourselves, if we’re too cavalier with our well-being and the well-being of those we love. These are plays that embrace the connection between the natural and supernatural worlds. They show us how vital our responsibility is to our spirituality, and what can happen if we turn our backs on our beliefs. This is what I’ve always loved about Greek Drama, and it’s why, as a writer, I continue to return to the Greeks and in particular, Euripides. Shakespeare’s work is another one for me.

JS: You rescue mythical figures rooted in our African traditions that are very present in our daily lives but sometimes ignored in our storytelling. I would like you to comment on that process.

DMP: I love the pantheon of the Gods. I love the choices this rewards us. We each get to have our own God. We each to get to have our own ideas about spirituality and spiritual beliefs. However, we live in a society that likes to tell us what to believe and what to worship. I was raised as a Catholic, not because it was my choice, but because I came from a family of Catholics. Yet, at the same time, my family retained their native, spiritual beliefs as Latinos. I grew up learning the stories of Santeria gods such as Ogun and Chango. As BIPOC people, we are especially encouraged to turn our backs on these kinds of beliefs. Anything to do with something other than the accepted and established is frowned upon. Or at the very least, it’s looked at as being eccentric, and maybe a little bit weird. When I got married, an African American Wiccan priestess officiated at our wedding ceremony, and married us in the name of Yemaya and Oshun. It would be an understatement to say that the guests were a little shocked! Yet to me, it felt like the most natural thing in the world. The spiritual beliefs that mark our cultural beginnings has the capacity to tell us who we really are and where we come from. I like “rescuing” these ideas because I believe it’s important to look beyond the more familiar, well-established dramaturgy of traditional coming-of-age, or kitchen-sink-domestic family dramas that infuse most contemporary Latinx narratives. I believe that all peoples and cultures have a sense of magic and the preternatural. In addition, as a Latinx theater artist, I want to create new myths within a culture that continues to be in great need of exploring its own narratives as Americans.

JS: We must recognize that there is still racism among the Latin-Americans, and your play speaks openly about the issue. How to write about racism without alienating your audience, and how does theatre play a role in changing our attitudes and political views in those regards, if any?

DMP: This is actually something I sometimes worry for as a writer because there is still so much left unsaid and undiscussed in the community itself. No one wants to talk about it. Yet it still exists. Internalized racism is real and it is something deeply felt and ingrained within the Latinx community. I feel that there’s this almost obsessive need within the community to show the more dominant culture that we all get along great. That we are all genuinely supportive of one another and it’s all “Kum Ba Yah,” you know? We’re all having drinks together every Thursday night. Well, we’re actually not. The Latinx is not a monolith. We don’t all know each other personally. We’re all individuals, and some of us will get along with some people, and with others, not so much. At any rate, dramaturgically, I believe it’s worth taking a look at, and as a playwright, I plan to continue to pick at that scab. I never really worry about alienating an audience because most of what I write is already strange. So, if you’re coming to see one of my plays you should expect to feel a little taken aback by something you see on the stage. In all honesty, I have always felt that this is the sort of thing that the theatre does best, but there are times now when I feel the theatre’s losing this. Sometimes it feels like it’s just about shorter attention spans and much more superficial, escapist entertainment.

JS: When we talked about your play, Ominous Men, you said, “I have noticed that in this era of #MeToo activism, there’s mostly been talk of wealthy and powerful white men and their horrific abuses against the women in their lives. However, I rarely see much discussion about the effects of domestic abuse, sexual assault, and violence that is perpetrated against women in the POC communities.” The topic of sexual abuse within the context of POC communities is again on the stage, but I think it’s a different angle in The Bacalao. The angle of revenge. Male revenge. Am I right?

DMP: The Bacchae itself is a magnificent revenge play. It is also a play of magnificent human suffering. When I first began work on my own version, I wanted for the theme of revenge to be all-encompassing and dynamic. The non-binary character of El Bacalao is fixed on revenge for the way their mother was brutally treated by her family. And to this end, they will stop at nothing, even if it means the loss of something dear and precious to them, which is what happens in the play. However, along with El Bacalao, it is the women of the play that are hungry for vengeance, hungry for a voice, hungry for some sort of an expressive release. There is a line in the play, “The women don’t speak here,” that is repeated continually throughout the story. This was deliberate on my part as I wanted to show how the women depicted in the play are suppressed and kept down by the ongoing misogyny, sexual abuse, and oppressive behavior exhibited by the male family members. When they are finally given the chance to “lose themselves to the scream,” as El Bacalao puts it, it ultimately leads to tragedy because they’re being controlled by a vengeful demigod who doesn’t really care about them and sees them as having been wholly complicit in their mother’s suffering. So, in the end, everyone loses.

JS: What’s the next project?

DMP: Along with these 2 readings at The Flea Theatre, El Bacalao is also part of the 2nd Annual BIPOC Adaptation Writers Workshop with Lifeline Theatre in Chicago. And another play, Sin Agua (Without Water), is part of the 2022-2023 Fighting Words New Script Development Program with Babes With Blades Theatre Company, also in Chicago. Both these companies are so cool and I’m very excited to be taking part in these programs, as well as looking forward to being in Chicago this summer! In addition, I also have the Michael Bradford Writers Residency coming up in August with the equally cool Quick Silver Theatre Company; we’re going to the Pocono Mountains!

That being said, however, I hope we’ll get lots of folks coming by to see the readings for El BACALAO: The Catfish Man in early May (5/5 & 5/6) at The Flea. In addition to having a great cast, the readings are being directed by a wonderfully talented SDC Director KM Jones with whom I’ve worked with before at The Chain Theatre with my short play, Dead Wives Dance The Mambo. The link for tickets is:

https://bit.ly/dqtpresentselbacalaothecatfishmanearlybirdtickets.

Thanks, Desi, for granting us this interview.

Dear readers, after seeing the play, go to a cuchifrito restaurant or make some bacalao at home. Aside from the tasteful experience, we may need to prove to ourselves that our palate is still working and that our past has not placed a curse on us.

Desi Moreno-Penson is a playwright, actor, dramaturg, and independent theater producer based in NYC. She has an MFA in Dramaturgy and Theater Criticism from Brooklyn College. Her plays have been developed/produced at Ensemble Studio Theater (EST), INTAR, MultiStages, Perishable Theater (Providence, RI), Urban Theater Company (Chicago), Teatro Coribantes (San Juan, PR), among others. Her play, BEIGE, won the 2016 National Latinx Playwriting. She has twice won the MultiStages New Works Contest. Desi lives in The Bronx with her wonderful partner, Anthony, and their cat, Choo-Choo.