11 October 1987. Attention! Breaking news. At 3:45 in the afternoon Jaime Pardo Leal, candidate for the presidency of Colombia for the Patriotic Union, was assassinated in the village of Patio Bonito in the municipality of La Mesa (Cundinamarca). The presidential candidate’s vehicle was surprised by a Renult 18, which hit Pardo Leal’s vehicle with several shots.

18 August 1989: Breaking news! Luis Carlo Galán, member of the Liberal Party and pre-candidate for the Presidency of Colombia, has just been shot while addressing his supporters in Soacha. The shot went through his bulletproof vest. Galán is dead.

22 March 1990. Extra! A few minutes ago, there was a shooting at the Bogotà air bridge, in which the Patriotic Union’s presidential candidate, Bernardo Jaramillo, was shot and wounded. We have just been informed that the presidential candidate, Bernardo Jaramillo, has just died.

26 April 1990. Attention Colombia! There has been a shooting inside an airplane. One of the passengers on the plane is Carlos Pizarro, presidential candidate of the M-19. We are informed that Pizarro has just died.

August 9, 1994. Attention! Senator Manuel Cepeda has just been assassinated, shot seven times. Two men in a white van committed the attack, supported by two others on a motorbike. Cepeda, 64, was the only senator of the Patriotic Union. He was a widower and had two children, Ivan and Maria.

Manuel left his home in the south of Bogotá at 8:30 a.m. on his way to the capitol. That day he left a little before Iván, his son, who hugged him goodbye. By then the threats were becoming more latent and Manuel’s death seemed closer, which is why Iván had taken the measure that every time he said goodbye to him, it would be as if it were the last time. At the height of Las Americas Avenue, Manuel’s bodyguard realised that a car was following them and that it was an attempt on Manuel’s life. Despite his attempt to defend the senator’s life, he could not. That was the day Manuel was assassinated.

An hour later, Ivan, who was on his way to the University, managed to see his father’s car in the avenue from the window of the bus, so he got out to go to the scene, thinking that it was a car crash. When he arrived at the scene, Ivan found his father’s body dead.

Manuel Cepeda was one of the victims of the extermination of the militants of the Patriotic Union (UP), a political party that emerged in 1985 as a result of the peace agreements signed between the government of Belisario Betancurt and the FARC guerrillas. However, the history of these thousands of militants who bet on peace was marked by the assassination of 4,153 of its members.

It is 1:00 am in Greece, where Maria lives with her husband and daughters. It is clear to her that she owes her most productive hours to the night. She logs on from her kitchen at home. The only noise that can be heard in the background of the Meet is that of the fan that she moves rhythmically to give herself air while she introduces herself and at the same time looks at the notes in her diary. “First of all, I want to tell you who I am,” will be Maria’s first proposal.

-I am Marìa Cepeda Castro. I have been living in Europe since 1984, when I had to leave to study in Bulgaria, for security reasons. I am a sociologist from the University of Sofia, I am married to a Greek and I have two daughters.

After a brief silence, she gathered the force to continue.

-But on top of that, I am the daughter of Manuel Cepeda and Yira Castro. They were two leaders of the Colombian Communist Party. Yira, my mother, died at the age of 38 due to health problems. She was a councillor in Bogotà and was a very prominent leader in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, while my father, Manuel Cepeda, became a Senator for the Patriotic Union and was assassinated on 9 August 1994 by paramilitary groups. He had denounced the links between paramilitarism and the military leadership. The extermination of the Unión Patriótica is part of many extermination plans. In fact, there were four plans linked to the genocide of the UP. My father was on the list of what was called the coup de grace plan.

My whole life has been – for as long as I can remember – a life of persecution, because we had a childhood where my parents were always harassed and searched for being communists, because at that time that was a crime. They almost wanted to drive the party underground, so its members were constantly persecuted. Our house was constantly raided by the police, both to look for my mother and to look for my father.

Maria stops and checks her mobile phone. She puts it on silent and, with the same lightness with which she expresses herself, with which she uses words, despite the pauses, she knows where she has finished and where to start again. And with a short, slow sentence she continues.

-So, then… our life has been full of many ups and downs.

Iván, now a Colombian congressman. He left the country in 1981, the year Yira died. María, the younger of the two, left Colombia in 1984. Their exile was due to the lack of security conditions for Manuel, Iván and María. “Our generation is that of that truncated history, of that generation that was not, that was blinded”.

-What I am telling you has to do with everything. This is the history of Colombia and it has to do with the National Strike, with the report of the Truth Commission and with the result of the last elections. It has to do with the war that our country has lived through and with the constant search for peace.

Migration for María is part of the story she tells her and her father.

-Your heart is broken in two and that piece that is there, in Colombia, continues to beat with great FORCE and you continue to feel in your body everything that is happening there. The fact that you are a migrant makes it hurt much more. You are like a snail; you carry your little house on your shoulders wherever you go. With the strike, I think that happened to most of us. It showed the barbarity of the police, where there were so many dead and disappeared. This generated a process of solidarity and sensitivity that we felt even though we weren’t there.

María is a daughter, sister and companion, but she is also the seed of a generation that was not intimidated by the orchestra of latent corruption between the state and paramilitarism, the same ones that could have preserved many political leaders who would have woven the path in recent years. María, like Iván, each in their own way, found a way, not only to vindicate her father and seek the truth, but also to defend human rights, Iván in Colombia and María abroad, together with the diaspora, leading processes such as Vamos por los derechos, the international chapter and the International Historical Pact.

When the UP was created, María was studying in Bulgaria, but her father told her that people were enthusiastic because it was the product of a peace agreement. Optimism was haranguing social change. The UP had a large number of representatives at the regional level who worked in the territory and in the communities. One day the assassinations began, afterwards another, another, and another.

-At first it was not believed to be a systematic practice, while party members had already denounced it.

Both Manuel and Aída Avella had taken the list to the Minister of the interior at the time, denouncing it as part of an extermination plan. A whole country witnessed how people died every day for having a political ideology, that of socialism.

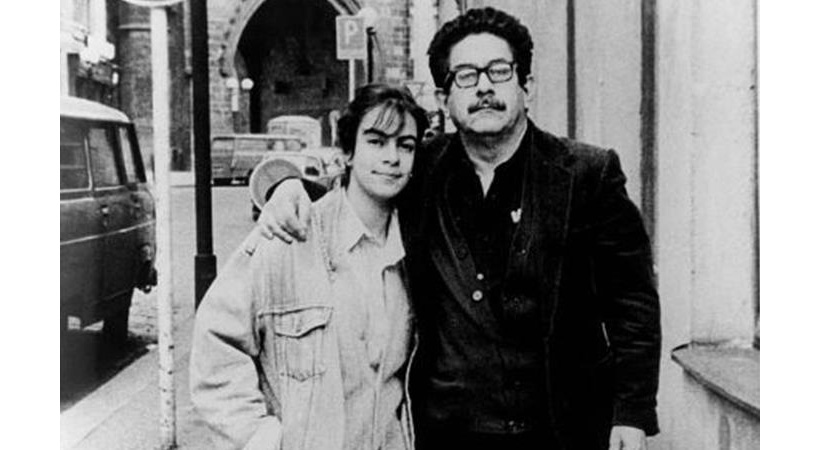

-My father came to Greece a month before he was killed, because he had been invited to a congress in Switzerland. Manuelita, my daughter, was four years old. He stayed with us for a week, we managed to take him to meet my in-laws, we travelled by boat, everything was very nice and then he left, we said goodbye. He told me that he was very threatened and was very sad because they had already killed a lot of people.

Manuel knew that he or Aida, his militant partner, would be next. For Iván and María, Manuel already knew that in the list of silence that fascism had drawn up, he would be next, which is why he went to Greece to say goodbye to them.

-I think there was a mistake in the strategy, because those people should have been removed it from the country,” says María.

For the UP members, it was a question of ethics and also of the right to live in Colombia and exercise opposition. Staying in Colombia meant staying in dignity, which is why the party members and leaders did not go into exile. It was about remaining communists, with their convictions intact and without hiding, which is why, despite being threatened, leaving Colombia was not an option.

-If they had left Colombia in time, we would have saved an important generation of leaders and we would not have had to wait so long for unity and peace.

On 16 January 2000, two army non-commissioned officers were sentenced to 43 years in prison as co-perpetrators of Manuel’s crime. Carlos Castaño also appeared in the sentence as the mastermind of the assassination. In 2010, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights condemned the Colombian state for the first time in the case of the assassination of a political leader, accompanied by a public act in which the state had to apologise and publicly acknowledge the facts of Manuel’s assassination.

For María, the moment that is being lived in Colombia is part of the historical struggle and she explains that the peace process was decisive for the National Strike to take place and to be able to celebrate today the results of the elections and the historic fact that, for the first time, the country has a government that is not right-wing or ultra-right-wing. “This would not exist without the popular resistance that the young people imposed on the streets,” he says.

-With the peace process, the internal enemy of the FARC, which was used to justify all kinds of violence, disappears. Then, with the disappearance of that ghost, people demystified the issue of protest and this was reproduced at the international level. That is when, as migrants and through the organisation that was being built, we ended up being an active part of this process and seeking, through political strategies, to protect the electoral process. In the same way, we managed to ensure that the migrant vote was representative in the last elections.

The result of the last elections is the path along which several generations passed, one after the other, looking for a way to detonate 214 years of naturalised fascism in the disguise of the oldest democracy in the continent. On 19 June, with collective anxiety, Colombia reached a turning point in its history when a former guerrilla fighter and an Afro-Colombian environmentalist and feminist leader became the first left-wing president and vice-president.

On that day, the struggle of Jaime, Bernardo and Carlos was embodied in a country, reminding us that the dream has always been peace and that “he who does not fight does not go to heaven”, as Francia Marquez often repeats in her speeches when remembering her companions from Cauca.

Of the thousands of images that circulated on social networks on the night of 19 June when we all remembered our dead, María remembers the photo of Iván Cepeda and Aída Avella embracing and crying, celebrating the election victory. That same photograph of Iván hugging Aída was taken at Manuel Cepeda’s funeral 28 years ago.

When María speaks of her father Manuel, her body rests, her pen and her smile become as profound as her memories with her father.

-My father was a very nice man. He was a funny person, he painted and made caricatures, he was very funny. He made fun of many things and liked to create things with his hands.

Maria remembers that for one birthday Manuel woke her up with a cardboard dove, and the Christmas tree in the house was decorated not with bought ornaments, but with plasticine ornaments made by Manuel, Yira, Ivan and Maria. Manuel was also a poet and writer and a great political analyst.

-My house was a communist household with all that that implied, with the sharing of the household crafts equally, but we hardly saw it. We were very good friends, there was a lot of trust, he was my great friend, imagine what it was like to lose him. He worked hard and everything he earned in parliament he gave to the party. He fought for the people who had the most difficulties.

My dad was branded for his character, but he was a very approachable person with a great sense of humor. Irony was one of the things that most characterised him, just like Pardo Leal, who was a great pedagogue. The auditoriums were packed to the rafters to listen to him, he was a very good teacher and he also had a great sense of humor. They were very nice people and had a well-developed degree of madness.

On 7 August, in a public act like no other in the history of Colombia, Gustavo Petro and Francia Márquez were sworn in and took the oath before the people. “Until Dignity becomes customary”. María Jose Pizarro, Carlos Pizarro’s daughter, with her father’s face printed on her coat and unable to control her tears, was the one who put the presidential sash on Gustavo Petro, while Afro, Palenquero and indigenous communities arrived in Bolivar Square.

The same week, 9 August, marked the 28th anniversary of the assassination of Manuel Cepeda, one of the many who with his struggle opened the way in a place where fighting for political, territorial and environmental ideals almost always means losing one’s life, and who today is part of the resistance that the region breathes. Today, Manuel, Yira, Dylan, Alison, Pizarro, Lucas and all those who died fighting, look down on us from heaven and remind us that “he who does not fight, does not go to heaven”. This earthly heaven is called victory and today we are living it.