PeaceDirect’s new report Peace, Race and Power explores how racism manifests itself in peacebuilding sectors. The 55-page report, produced through global consultations involving more than 160 people from 70 countries, builds on the findings of the May 2021 report Time toDecoloniseAid, which found systemic racism in the humanitarian, development and peacebuilding sectors. The report was produced in collaboration with the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict (GPPAC), the International Civil Society Action Network (ICAN) and the United Network of Young Peacebuilders (UNOY).

Decolonising Peacebuilding Processes

The Oxford definition of decolonisation is “the process by which a colony or colonies become independent”, but the meaning of the word can vary depending on one’s geographical location. In South Africa, decolonisation movements have linked the word to economic issues, such as access to quality education, higher education, land and healthcare, among others. These movements also seek to dismantle what are seen as Western and colonial systems and structures of knowledge production and dissemination. In order to unravel decolonisation, the psychological effects caused by colonisation must be recognised and addressed.

NicolineNwenushiWazeh, a gender and development specialist and peacebuilder from Cameroon, gives as an example the current crisis the country is facing as a real consequence of colonialism.

“In Cameroon we are facing a situation that has been going on since 2014 in which English-speaking Cameroonians, who are in the minority, find it difficult to live with French-speakers, who are in the majority. Before colonisation we had one Cameroon and this situation was brought to us by the colonial masters, the British and the French, and today it is difficult for us to go back to the one Cameroon that we were and many lives have been lost because of it,” he says.

Wazeh says peacebuilding processes must be decolonised because the communities on the ground are more than capable of talking about their own problems and they have the urgency and they know what they want and they can speak for themselves, they just want partners to give them space and an opportunity to build capacity to be independent.

“As much as the UN Sustainable Goal 17 talks about partnerships for development, I believe in this partnership which is indispensable in a world that has become globalised, but it cannot be one-size-fits-all. We cannot use a broad solution to solve problems. Some problems are specific and need a specific approach,” he says.

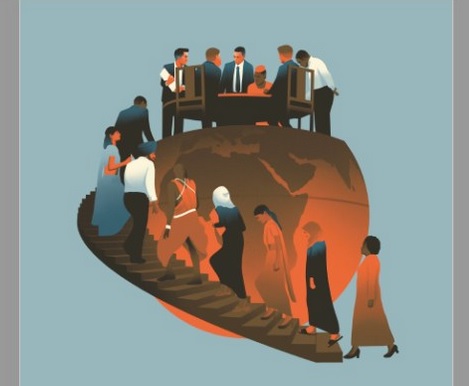

RaavalBains, head of research at PeaceDirect and co-author of the report, argues that colonialism was created by greed and the lust for power. As a peacebuilder based in the UK, which is part of the Global North, Bains says there is a problem of ego and arrogance in the Global North towards the Global South.

“We think what we think and how we think is the right way, what we do is the right way to do. How we are is the right way to be. Colonialism was created by greed and the lust for power. Ego is one of the most entrenched problems we have in the Global North and one of the biggest obstacles to developing partnerships,” she says.

Shannon Paige, policy associate at PeaceDirect and lead author of the report, says that for meaningful partnerships to exist, there has to be equality.

“Throughout the different days we held the consultations, a key element that came up again and again was the lack of recognition of urgency, of resources, of capacity and capability, and that encompassed everything from the belief that local communities were not well equipped to solve their own peace problems, to the idea that they needed external actors to help them as a neutral figure,” she says.

How structural racism manifests in peacebuilding

The report names several factors that slow down peacebuilding processes and manifest themselves as racist, including peace interventions through the assumption that actors from the Global North can “fix” the problem in other countries and should therefore always intervene directly. Also, Global North-specific attitudes and assumptions about the superiority of their knowledge and experience in conflict and peacebuilding issues and the lack of capacity in the Global South.

The report also mentions that funding mechanisms are non-transparent and inaccessible to most actors in the Global South and are often designed with Global North INGOs in mind. Participation is another factor noted, as Global South actors are often seen as victims, perpetrators or potential perpetrators of violent conflict, which means that Global South agencies and their peacebuilding capacity are often overlooked.

Recommendations

The report concludes that the peacebuilding sector continues to neglect local peacebuilders, who are most affected by and closest to conflict. It goes on to recommend that actors in the Global North, including international organisations (UN, World Bank, OECD, etc.), governments, INGOs and think tanks, acknowledge that structural racism exists and rethink what counts as expertise¸ actors in the Global North must consider that their expertise may not be the most relevant. Peace, Race and Power warns that the peacebuilding sector can no longer exclude local actors from leadership and decision-making spaces, nor can it continue to ignore the bias inherent in their efforts.