ENDANGERED SPECIES ESSAY

We must safeguard the web of life and care about the other living species that we share this planet with. Pygmy tarsiers eat and host bugs that we’ve seen at home — insects, spiders, lizards, bedbugs, lice, fleas, roundworms, and tapeworms. The vaquitas are preyed upon by large sharks and killer whales, keeping them away from us. But only 10 vaquitas are left and in their absence, the diet of sharks and whales may change. A tiger in the wild indicates that the forest it inhabits is healthy and diverse. As of now, there are 3,900 tigers in the wild globally, and more than twice as many (8,000) in captivity. By protecting the web of life, we build a kinder world for everyone.

“It would be such a pity if these remarkable animals vanish from our planet and remain confined to the pages of a book or in photographs.” ~Maritess Gatan Balbas, Chief Operating Officer, Mabuwaya Foundation

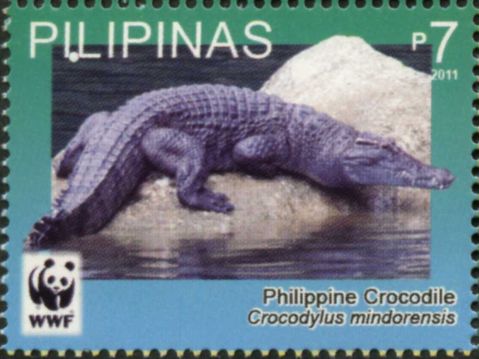

In 1999, Maritess Gatan Balbas, COO, Mabuwaya Foundation (MF), met her first Philippine crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis), which had long been believed to be extinct in Luzon. Her oxytocin rose as she fed and raised the croc. By 2001, the NGO that she worked for shut down, and she worried about the Philippine crocodile’s future.

That same year, Philippine crocodiles rose in numbers from allegedly extinct to 12 individuals. It had a unique, even temperament. Balbas didn’t want the species to lose its future.

Balbas is the daughter of farmers. She loved forests and specialized in social forestry. She was later trained to be a community organizer under the Mabuwaya Foundation (MF) on behalf of the croc.

The MF was formed in 2003 and funded by the Conservation Leadership Program (CLP), which since 1985 matched funding and training with difficult conservation programs.

The MF, located in Isabela Province, initially focused on data gathering and conservation, but it soon became clear that they needed someone who could make locals and politicians love the Philippine croc. Balbas was hired to do this in 2004.

Spreading love for the Philippine croc

Balbas worked with communities on the forest’s fringe and in remote mountain neighborhoods along the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park in Luzon (NSMNPL). This was doable because she speaks all the languages of the locals, namely Ilocano, Ibanag, and Tagalog.

She matched the local government with communities and launched intensive communication campaigns. Children were thrilled by Philippine croc storybooks, field trips, and puppet shows. Adults were charmed by the Philippine croc through crocodile festivals, posters, calendars, and lectures.

Balbas jokingly began presentations by saying, “like me, (the Philippine crocodile) is small, shy, beautiful, and doesn’t attack unless provoked”.

Awards

In 2005, MF won a CLP Leadership Award, which was used to build and train their team with overseas education in wildlife management, crocodile handling techniques, and animal husbandry.

The CLP also leveraged funds for MF’s CROC project, which stood out as a model for community-based conservation. The project established 17 freshwater protected areas guarded by locals and over 100 captive‐raised Philippine crocodiles that were rewilded.

In 2014, Balbas won the Whitley Award or “Green Oscars” for her work with Philippine crocodiles. In 2020, a second Whitley Award supplied funding to continue the program. Through her efforts, farmers realized that the Philippine crocodile is their “assistant” because it eats rice field pests like introduced golden apple snails, and introduced rats.

To buttress the Philippine crocs’ ecosystem benefits, communities were trained in environmental stewardship. They learned that by shifting from agriculture to agroforestry, (which blends crops and/or livestock with trees and shrubs), they could prevent erosion, and raise productivity and profitability. It strengthens an ecosystem, making it adaptable, sustainable, and healthier for humans.

Balbas, her team, and other conservationists successfully grew the 12 crocodiles existing in 2001 to 100 by 2012. Today, there are between 92 and 137 mature Philippine crocodiles in the wild.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) ranks the Philippine crocodile as Critically Endangered. If we lose them, they’ll be gone forever, all over the world. This croc is the most endangered crocodile species globally.

Unique character

Normally, a bask of crocodiles imbibes the sun together. But the Philippine croc is a loner and is only seen with another crocodile when mating.

The female Philippine croc builds the nest. A mound nest is preferred due to the weather (which determines the sex of the crocodile). However, if killer ants are in the area, the mother will make a hole nest instead.

The Philippine crocodile is comparatively small at 10 feet long when fully grown, or half the size of the Crocodylus porosus, another crocodile in the Philippines, at 20 feet.

The two crocodiles are opposite in character. The latter is an aggressive man-eater that also eats buffalo, monkeys, turtles, and wild boars, among others. The Philippine crocodile would rather hide from humans than strike them. They eat fish, small mammals, and some birds, among others.

This timid croc is easy prey for hunters. Other threats are habitat loss amid continuing human population growth and expansion, and entanglement in fishermen’s nets.

Record of releases in the wild

Philippine crocodiles have been successfully bred in captivity and rewilded in protected areas. They’re released as juveniles when they’re adaptable to a new habitat. Here are some stories of rewilded Philippine crocs:

July 2009. Fifty juvenile crocodiles (10 of which had radio transmitters attached) were released into Dicatian lake, Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park.

It was an arduous journey that began with crating the 50 crocs on July 28, 2009 in Puerto Princesa, Palawan. The next day the crocs flew by airplane to Manila. On July 30 they took a 12-hour bus ride to Isabela. Finally, on the 31st, armed forces helicopters flew the crocodiles to the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park (NSMNP), among the largest and most important protected nature parks in the country, situated within the Sierra Madre Biogeographic Zone (SMBGZ).

March, 2013. Some 36 juvenile crocs were rewilded in the Paghungawan Marsh, Siargao Island Protected Landscapes and Seascapes (SIPLAS), by the Siargao Island Crocodile Research and Biodiversity Conservation (SICRBC) Project.

The freshwater Paghungawan Marsh is part of SIPLAS, a 278,914.131 hectare protected nature park, with the largest marine protected area in the Philippines. Many amphibian species that are new to science are found here, as are newly-discovered flora and fauna species.

2017. Twenty-nine juvenile Philippine crocodiles were rewilded in SIPLAS. While monitoring them, scientists learned that some “lost” Philippine Crocs that were released in 2013 were doing something unusual – climbing up steep mountain slopes 52 feet high, and/or up 50-degree slopes of limestone walls, rather than staying near a water source.

This new knowledge helped improve future rewilding plans. They also learned that Philippine crocs can bury themselves deeper into mud holes along the water line than expected, to stay cool in the hot, dry season.

2018. The Crocodylus Porosus Philippines Incorporated (CPPI) installed radio transmitters on two mature crocodiles in Pilar town and rewilded them so they could study how far Philippine crocs travel in protected wetlands. This data will be used when determining the suitability of future areas for rewilding Philippine crocs.

November 2020. Two crocodile nests with eggs were discovered, indicating that captive-bred Philippine crocodiles were reproducing in the wild. Surprisingly, the eggs were laid in October. The usual months for nesting are March and July.

Under R.A. 9147 (the Wildlife Act) killing a Philippine crocodile is illegal, with a penalty of a minimum six years’ imprisonment and/or a fine of P100,00o. So far, no one has been convicted, and authorities rationalize that people are poor and matter more than crocodiles.

A senior government official said all dangerous crocs in a protected area were killed and eaten by Moro hunters and the military to protect people.

Ironically, rather than keep people safe from crocodiles, they deprived humans of a healthy ecosystem that crocodiles provide for all dwellers in it. A crocodile is like an ecosystem policeman.

Officer crocodile

Humans need crocs, including man-eaters, to enrich the ecosystem. Crocodile waste provides nitrogen and phosphorus, which are needed by plants and microorganisms, making them rich food for other animals in the ecosystem, such as small insects, birds, crustaceans, and of course fish. Crocodile droppings also contain critically important chemicals that are nutritious for fish.

Crocodiles eat a large amount of sick and rotting fish in the wild, leaving a larger share of healthy fish for fishermen, humans, and other animals. They improve the health of fish stocks.

Crocodiles also keep fish species numbers balanced and proportionate. If a fish species gains sudden dominance, the crocodiles will eat the dominant species to even things out.

In sum, a single crocodile plays a vital role in forming a big, balanced, and healthy latticework-like food chain within an ecosystem.

Interesting facts about the Philippine crocodile

Other interesting facts about the Philippine crocodile are:

They were prehistoric animals that survived the extinction of dinosaurs.

In pre-Hispanic times, Philippine locals in the northern Sierra Madre co-existed with crocodiles. Their relationship was characterized by fear and reverence. Rules determined how people and crocodiles related together, enabling them to share land and water with this powerful animal.

After World War II, crocodile numbers were severely depleted by commercial hunters who used its skin for leather.

Indigenous communities respect and know about crocodiles, but outsiders tend to presume that all crocodiles are man-eaters.

Across the densely populated country, marshes, swamps, and creeks were converted to rice fields, destroying the crocodile’s habitat. Overfishing, fishing with dynamite, electricity, and the use of pesticides further reduced the croc numbers.

When the MF built eight crocodile sanctuaries, they noticed that erosion lessened, water was cleaner, and the population of fish was higher because of these sanctuaries.

Philippine crocodiles spend a lot of time on land. A radio-tagged crocodile was presumed dead after spending a week in the forest, but when the MF found it, it was alive and thriving.

Philippine crocodiles find shelter in caves, in both the Cordillera and Sierra Madre Mountains. They also dig tunnels in clay and sandy river banks.

Juvenile Philippine crocodiles in captivity, aggressively fight each other. In the wild, they also aggressively establish their individual territories.

As adults, they mellow and pair up with mates, relaxing and swimming together.

Both partners share nest guarding duties.

Some radio-tagged crocodiles traveled from 1 km to 6 km in northern Luzon.

The gender of Philippine crocodiles is dependent on the incubation temperature of the egg.

The only reported predator or Philippine crocs are humans. The Crocodylus porosus might attack them, but they were observed cohabiting in a single location on Mindanao. People kill these animals for their skins and meat, to protect their livestock, and to ensure their own safety.

The Philippine crocodile is most threatened when it travels beyond protected areas, making them vulnerable to humans.

For 70 years, (as of 2020), people didn’t know that the Philippine crocodile thrived undiscovered in Malabang town, Lanao del Sur province. First, because the Maguindanaon, Manobo, and Maranao tribes believe the Philippine crocodile is a reincarnation of their dead relatives. Second, there has been an ongoing armed conflict in Lanao del Sur since the late 1960s.

The first Philippine croc was found in the area on November 28, 2019, by Saino Benito Pagayawan, a police officer and a former DENR forest ranger.

It seems that hope for the crocs lies in some cultural traditions that respect them, and the sad distraction of war.