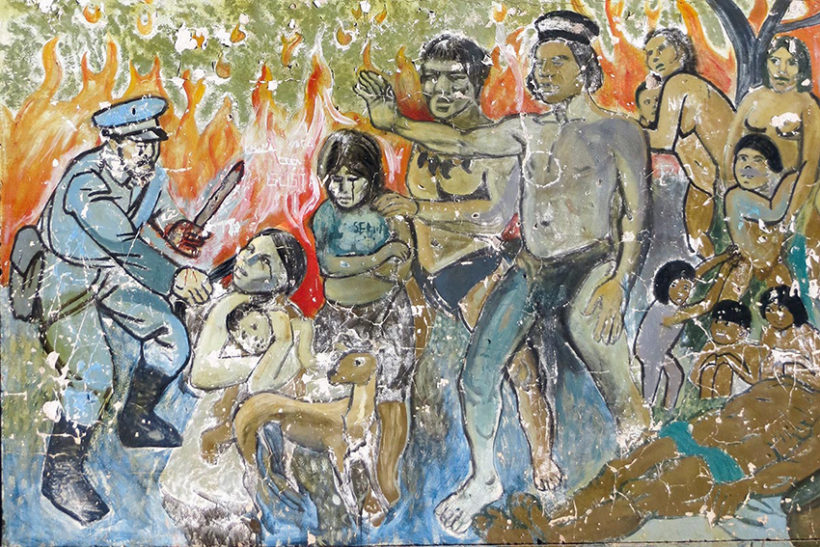

In 1924 hundreds of Qom and Moqoit Indians were murdered in Chaco. The massacre was silenced for decades, but it remained alive in the memory of the native peoples, who transformed it into a struggle and demand for justice. Federal courts confirmed a “trial for the truth” to determine those responsible and, centrally, the role of the state in the violation of rights.

By Ailín Bullentini/Agencia Tierra Viva

“My mother shed tears every time she remembered that horror, but she made the effort to overcome it to seek historical reparation,” says Sabino Yrigoyen, one of the 12 children born to Melitona Enriquez, one of the last survivors of the Napalpí Massacre. Melitona died in 2008 without knowing that, many years later, that effort to tell the story of the massacre in which much of her community was killed would bear fruit. At the beginning of the month, 13 years after her death and almost 100 years after the event, the Federal Court authorised a trial for the truth to bring “historical and symbolic reparation” to the original Argentinean peoples who were repressed, persecuted, hunted, murdered and denied. The fact was confirmed by the justice system as a crime against humanity.

Sabino continues to live in Chaco, and from there he speaks to Agencia Tierra Viva in light of the news that updates the struggle of his mother and the entire Qom and Moqoit community in the area: The head of Federal Court No. 1 of Resistencia, Zunilda Niremperger, authorised the processing of a trial for the truth about the crimes against humanity committed on 19 July 1924 and its subsequent days against members of the Qom and Moqoit peoples, who at the time were carrying out a strike in their clearing work to demand better working and living conditions. They were repressed and persecuted. Between 200 and 300 members of these communities were killed. Their bodies were burned or buried in mass graves. And the facts were distorted and denied by the national authorities.

Sixteen years ago, a civil trial began for the massacre, which was successful for the communities this March in the Resistencia Court of Appeals. It was a civil trial in which the national state denied its responsibility. However, in parallel, the provincial Prosecutor’s Office began to investigate the events from a criminal perspective in 2014, in a task led by its Human Rights Unit. In 2014 it initiated a formal investigation with the aim of clarifying the facts and, above all, to provide reparation to the community.

“We sought from the beginning to address the right to truth of the victims and their families, on the one hand, but also to generate an act of historical reparation for the people,” said the ad hoc prosecutor Diego Vigay, who shares the specialised Human Rights Unit with the general prosecutors Federico Carniel and Carlos Amad, and the federal prosecutor Patricio Sabadini. Last July they asked the judge for a trial for the truth, which she responded satisfactorily in early September.

A truth trial: implications

“We understand that this is the appropriate tool for the national state to comply with its international commitments to judge these crimes beyond the time that has passed and the procedural impediments such as the fact that there are no living perpetrators,” Vigay explained to this agency after receiving the great news: for the first time, the federal justice system will hold a trial for the truth to review these events.

The preliminary investigation lasted six years, during which the team gathered testimonies from victims’ relatives, survivors, audiovisual journalistic material from recent years and from the period, academic research, archives, contributions from specialists in different related subjects – from indigenous genocide to aircraft experts – and even conclusions from excavations carried out by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team in the area.

The result was certain: what happened in the Napalpí Massacre was a crime against humanity on the part of the Argentine state. But those responsible were identified, from the President of the country Marcelo T. de Alvear and the Minister of the Interior, Vicente Carmelo Gallo, the authorities of the Napalpí Reduction to the chiefs and officers – dozens of them from the Napalpí, Quitilipi and Roque Sáenz Peña units of the Chaco Police, the National Territories Police and the Gendarmerie – are all dead.

A trial for the truth was therefore requested, taking as background the so-called trials that took place during the late 1990s in different jurisdictions to investigate the crimes of the last ecclesiastical civil-military dictatorship. Those responsible for those crimes were not dead, but benefited from the laws of Due Obedience and Full Stop. Many of them went unpunished and even testified in the trials for the truth.

In light of this fact, for Judge Niremperger, “historical and symbolic reparation to the communities that were directly affected by these events” is as important, if not more so, than the distribution of individual criminal responsibility. The magistrate highlighted that “there is an accentuated mandate of due diligence that weighs on the Argentine State, since those who would be victims of the events in question are members of the Qom and Moqoit indigenous communities” and based on this, she considered it “necessary to go through a process that establishes the truth of what happened due to its symbolic, historical and human value, seeking the judicial determination of such events”.

Thus, the judge confirmed the category of crimes against humanity for the repression, massacre and persecution that constituted the Napalpí Massacre, “whose imprescriptibility makes it possible to investigate, despite the time that has elapsed, and thus to seek its reconstruction from a historical perspective”.

This is not the first original massacre at the hands of the state to carry this qualification: in 2019, the Rincón Bomba Massacre of the Pilagá people in Formosa was also classified as such.

In the case of Napalpí, the step forward is the trial for the truth. “It is what my mother sought all her life and what we were longing for,” said Sabino. Melitona was 107 years old when she died. She did not get to testify in person before the prosecutors, but her story came through anyway.

The road to the truth about the Napalpí Massacre

Sabino was one of Melitona’s sons who brought his mother’s experiences to the Prosecutor’s Office, an account that she kept alive through oral tradition among her family. “In a very interesting process, as it was a taboo subject in the family, in the community, traumatic and silenced by terror, the communities were discovering the testimonies of the survivors,” said Vigay. The team was able to add the testimonies of four survivors: Melitona, Rosa Chara and Rosa Grilo (from the Qom People) and Pedro Balquinta (from the Moqoit People). The latter two made their contributions in person. They were all children at the time of the events. They saved their lives by running for weeks in the mountains hand in hand with an older relative.

The conflict was concentrated in the community of Napalpí, some 130 kilometres from the provincial capital, a concentrated area in the hands of the national state, which exploited the native hacheros in the worst possible way and savagely repressed them in the face of that protest. Between 200 and 300 men and women, old people, young people and children died as a result of the shooting with which 130 members of the National Territories Police and Gendarmerie attacked a community meeting for at least an hour, without stopping. Children, women and men were chased through the bush and hunted to death. Even a plane was used for intelligence work to determine how many and who were demanding improvements. The remains of the victims were disposed of in bonfires or mass graves.

The contributions of historians specialising in Argentina’s original plot were also fundamental to the investigation. Among them, the historian Juan Chico, together with David García, Mario Fernández, Juan Carlos Martínez, Raquel Esquivel and the men and women of the Napalpí Foundation.

For historian Marcelo Musante, who contributed to the case and is a member of the Network of Researchers in Genocide and Indigenous Politics, the arrival of this trial “responds to the efforts of the people of Colonia Aborigen – which is what Napalpí is now called, where the massacre took place – who kept alive the memory, the struggle for truth and justice despite the terror and fear, who were able to tell generation after generation what happened, and historians like Juan Chico, who worked tirelessly for 15 years – he died last June”. And he remained expectant about the “impact” that the oral and public debate will have, as “we will have to see what concrete actions are taken”.

Last July, the Chaco and national Human Rights Secretariat participated in the marking of the place where the event took place as a site of memory. “Crimes against humanity were committed here”, says the sign erected at a point in Colonia Aborigen, similar to the one that identifies clandestine centres of the last civil-military dictatorship. Secretary Horacio Pietragalla took part in the ceremony.

The marking “is part of a state policy of recognising serious human rights violations, such as Napalpí and others, and of seeking different forms of reparation” for the communities that suffered them, Federico Efron, director of National Legal Affairs in Human Rights Matters at the Secretariat, explained to this agency. The department contributed an investigation to the federal case for Napalpí, carried out by historian Alejandro Jasinski, which the prosecutors of the specialised unit described as “exhaustive” and “valuable”.

The work, of more than 250 pages, inscribes the events in a “repressive context” not only against the native communities, but also against the working class people throughout the territory. It reaffirms that the massacre was carried out by a hundred policemen and civilians on the orders of Fernando Centeno, who was president of the Chaco territory and governor, and denounces the cover-up by all branches of government. “Despite some denunciations, the massacre did not transcend or produce an impact that would force those in charge of the state to investigate the facts. A parody of a police investigation covered up the horror. The judicial apparatus closed the case. The investigations got bogged down in Congress. The executive branch shirked its responsibility,” Jasinski said.

Next steps

The judge authorised the Official Public Defender’s Office of the Victim, the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Secretary of Human Rights and Gender of Chaco as plaintiffs in the debate. A date must now be set for the preliminary hearing in which evidence – historical documents, witnesses, reports – must be presented. Once the evidence has been offered, the judge will have time to analyse it without strict time limits and only after defining which elements will be part of the trial and which will not, will she set a date.

The interesting thing about the debate, Musante hopes, is that “the process and the context” in which the massacre took place “can be put on the table so that it can be understood that it was not an extraordinary event, but that everything was in place for Napalpí to happen at some point”. The state as exploiter, as abuser, as annuller of the native peoples. In this context, the historian points out, “it is important to give names and surnames to all the people who participated, civilian actors who took part, state institutions that took part in the massacre. This was not part of the civil trial and it is fundamental”.

As for the possibilities that this debate opens up for the future regarding the original genocide that the Argentine state carried out in the country, the possibilities are also diverse. “It is a big step for the state to recognise a massive state massacre against the natives, and hopefully it will allow us to begin to think about genocide in a broad sense, what happened with the so-called ‘Conquests of the Desert’, something that the state has never considered”, said Musante.