Lewontin fought a lifelong battle against racism, imperialism and capitalist oppression.

By Prabir Purkayastha

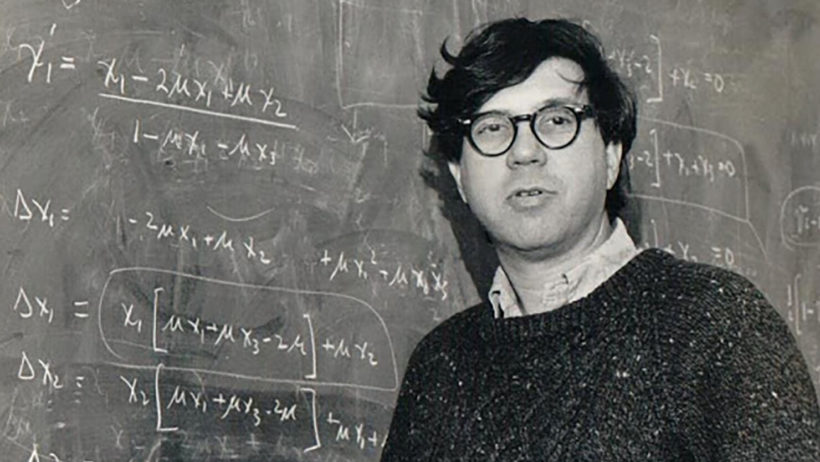

On July 4, Richard Lewontin, the dialectical biologist, Marxist and activist, died at the age of 92, just three days after the death of his wife of more than 70 years, Mary Jane. He was one of the founders of modern biology who brought together three different disciplines—statistics, molecular biology and evolutionary biology—that mark the discipline today. In doing so, he not only battled crude racism masquerading as science, but also helped shed light on what science really is. In this sense, he belongs to the rare group of scientists who are equally at home in the laboratory and while talking about science and ideology at a philosophical level. Lewontin is a popular exponent of what science is, and more pertinently, what it is not.

Lewontin always harked back to what being radical means: going back to fundamentals in deriving a viewpoint. This method is important, as it makes radical inquiry a powerful tool in science, compared to lazier ways of relating positions to certain class viewpoints. What is the relation between genes and race, class, or gender? Does social superiority spring from superior genes, or from biological differences between the sexes? As a Marxist and activist, Lewontin believed that we need to fight at both levels: to expose class, race and gender stereotypes as a reflection of power within society, and also at the level of radical science, meaning from the fundamentals of scientific theory and data.

Richard Lewontin and the population geneticist and mathematical ecologist Richard Levins shared a passion for biology, social activism and Marxism. It is not so well known that Lewontin’s close friend Stephen Jay Gould—the paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and popular science writer—was also a fellow Marxist. All three of them fought a lifelong battle against the racializing of biology and, later, sociobiology, which sought to ‘explain’ every social phenomenon as derived from our genes. Evolutionary biologists E.O. Wilson and Richard Dawkins—and many others—believed that humans are programmed so that society merely expresses what is already embedded in our genes. Through their eyes, white races are superior because of their genetic superiority; as are the rich. In India, there is also a genetic theory of caste to explain the supposed differences between caste groups. And as long as there are significant differences between groups of people—based on class, race, gender or caste—biological ‘explanations’ for these differences will be offered.

One of Lewontin’s pathbreaking works was to find out how much genetic diversity exists within species. This was at a time when we did not know how many genes humans had. Lewontin’s inspired guess was 20,000, far smaller than what most biologists thought then and remarkably close to what is known today. Most biologists then also believed that races had significant biological differences, which was one of the reasons why they thought that there was a much larger number of genes carrying different traits. Lewontin and geneticist John Hubby used a technique, protein gel electrophoresis, developed by Hubby, to quantify the genetic diversity in fruit flies. At that time, fruit flies were the favorite target for testing genetic theories in the laboratory. This pathbreaking exercise traced evolution at the species level to changes at the molecular level—a foundation for the field of molecular evolution—using statistical methods. The result was startling. Contrary to what most biologists believed, the exercise showed a surprising amount of genetic diversity within a given population and further revealed that evolution led to stable and diverse populations within a species. Later on, Lewontin used this method on human blood groups, to show that the result of stable genetic diversity held true for humans as well. The other result of the human blood group study was that it showed that 85.4 percent of the genetic diversity in humans was found within a population, and only 6.3 percent between‘races.’ Race was not a biological construct but a social one.

Lewontin went on to co-author a paper along with Stephen Jay Gould on how evolution is not directed to develop every feature that we see in an organism today, but is also the result of accidental offshoots accompanying a specific genetic change that occurs due to evolutionary pressure. Gould and Lewontin likened it to spandrels in architecture. When an arch is carved out of a rectangular wall (say, a door), the triangular part left between the arch and the wall is called a spandrel. This is also what happens when domes rest on rectangular structures. That these spandrels are then carved and decorated is not the reason for their existence, but once created, they can be used for other purposes. Similarly, in species, nature makes use of accidental offshoots of an evolutionary change, just as those who built arches or domes do with spandrels.

What distinguished Lewontin’s popular and scientific writings were his ability to connect the larger issues of science to society and his critique of the crude reductionist understanding of biology. He called it the Cartesian fallacy: that if we can break up the parts of a whole into its constituent parts and find the laws of the parts, we can then assemble the whole and understand it fully. Of course, this Cartesian viewpoint is no longer viable even in physics, let alone to explain chemistry from physics, biology from (organic) chemistry, or society from biology.

Why, then, does this view recur, particularly in understanding inequalities in society? Lewontin traced this repeated attempt to give biological explanations for inequality to the deep structural inequalities within society. This hydra-headed monster will rear new heads again and again as long as structural inequalities exist in society. This was the battle that he and his close colleagues fought against, racism, the fallacy of putting stock in IQ tests, and sociobiology, which sought explanations for all social inequalities in biology, i.e., that inequalities were preprogrammed in our genes.

This was the lifelong battle that he carried out not only in his specific field of biology but also in the larger domain of sciences. His ideological struggle against racism, class and imperialism was not separated from his science. He saw it as an everyday struggle within sciences as well as outside them, to be fought at both levels: at the level of society as well as at the level of science. He did not simply argue that race was a wrong way of looking at societal differences but showed it with hard experimental data and a theoretical framework to explain that evidence. This was his integrity as a scientist and as a social activist.

A large number of progressive scientists in the United States came together in the late ’60s and early ’70s, forming an organization called Science for the People. It has been revived recently. The organization was a reflection of the anti-racism and anti-war movements in the United States of that time. Their discussions on science and society paralleled what science and social activists were experiencing in India that led to the people’s science movement, and resulted in the formation of the All India People’s Science Network. In the U.S., Science for the People decided to become more of a movement within the scientific community, while the movement in India decided that it should be a larger people’s movement not only on the issues of science and society but also by building scientific temper in society.

The recent Netflix film “The Trial of the Chicago 7” depicted the ’60s struggle against the Vietnam War. Bobby Seale, a co-founder of the Black Panthers, was one of the people who was charged in the trial by the U.S. government with “conspiracy charges related to anti-Vietnam War protests in Chicago, Illinois, during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.” (A much better film is the older HBO movie “Conspiracy: The Trial of the Chicago 8,” which is available on YouTube.) During the trial, the Chicago police assassinated Fred Hampton, an important Black Panther leader there who was helping with the defense of Bobby Seale. I will let Lewontin and his close comrade Levins, co-authors of Biology Under the Influence, tell us in their words how they related to these movements:

“We have also been political activists and comrades in Science for the People; Science for Vietnam; the New University Conference; and struggles against biological determinism and ‘scientific’ racism, against creationism, and in support for the student movement and antiwar movement. On the day that Chicago police murdered Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, we went together to his still bloody bedroom and saw the books on his night table: he was killed because of his thoughtful, inquiring militancy. Our activism is a constant reminder of the need to relate theory to real-world problems as well as the importance of theoretical critique. In political movements we often have to defend the importance of theory as a protection against being overwhelmed by the urgency of need in the momentary and the local, while in academia we still have to argue that for the hungry the right to food is not a philosophical problem.”

Biology Under the Influence, a collection of essays by Levins and Lewontin published in 2007, was dedicated to five Cubans—the Cuban Five—who had infiltrated Cuban American terrorist groups in Miami that were actively supported by U.S. agencies. They were then serving long prison sentences in the United States.

Lewontin and Levins were both Marxists and activists and fought a lifelong battle against racism, imperialism, and capitalist oppression. They brought their Marxism to biology and its larger philosophical issues. They dedicated their 1985 book, The Dialectical Biologist, to Frederick Engels, “who got it wrong a lot of the time but who got it right where it counted.” This also applies to Lewontin, who also got race, class and genetics right where it counted.

This article was produced in partnership by Newsclick and Globetrotter.

Prabir Purkayastha is the founding editor of Newsclick.in, a digital media platform. He is an activist for science and the free software movement.