Julia Taleb, August 22, 2014, for Waging Nonviolence

In July of 2013, when activists in the Syrian city of Raqqa feared demonstrating in front of the headquarters of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, Suad Nofel marched onto the streets alone. Holding her handmade cardboard sign, the schoolteacher walked through the city facing not only ISIS, but society as a whole. Nofel’s act of nonviolent resistance later became known as the one-woman rally.

Nofel made her way to ISIS’s headquarters every day for three months. Each time, she spent almost two hours rallying with a new sign, with messages such as, “Don’t tell me about your religion, but show it in your behavior!”and,“No for oppression, no for unjust rulers, no for atonement, and yes for thinking!”

Almost two years earlier, hundreds of thousands of Syrians took to the streets asking for the trial of Daraa’s governor, who was responsible for the arrest and torture of the children that triggered the popular uprising on March 2011. People from diverse ethnic, religious and social backgrounds peacefully protested against the regime and demanded more rights and freedoms. During that time, nonviolent resistance won concessions from the government, including dismissal of Daraa’s governor, the release of hundreds of political dissidents, and the removal of the Emergency Law, which had been in effect for 48 years.

“Online coordination and messages were replicated on the ground through leaflets, graffiti and chants,” said Zoia, a female Alawite activist who preferred to use her first name for security reasons. “The regime’s brutality backfired and it created more sympathizers among neutral actors.”

With the establishment of the Free Syrian Army, or FSA, in July 2012, various armed groups joined the fight, including the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS — a jihadist militant group in Iraq and Syria that declared itself to be a caliphate with absolute religious authority over the population under its control. More than 11,000 foreign jihadi fighters have also entered the country, all vying for power.

After the resistance became armed, ISIS emerged as the strongest and most brutal force in Syria. It now controls 60 percent of Syrian oil and the highest wheat producing areas in the country, including Deir Elzzour, Hassakah, Idlib and Raqqa.

“I couldn’t witness innocent people being arrested, plundered, kidnapped and executed by ISIS,” Nofel said. “We were silent for 43 years of the regime’s oppression and I wouldn’t accept another tyrant.”

When the regime’s forces withdrew from Raqqa on March 5, 2013, the FSA took control initially. During this time, people were establishing civil organizations including the local councils and women’s organizations, a member of the FSA explained.

“We initiated Jina, a women’s organization to promote the role of women in various sectors,” Nofel said. “We founded sewing and food manufacturing projects to secure job opportunities for women, especially widows.”

Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al Sham, ISIS and other Islamic battalions existed in Raqqa, but they were not as powerful. At the time, many people thought that these groups were there to liberate them from Assad’s forces, a member of the FSA said.

As ISIS grew in power, it killed members of the FSA and gradually took over the whole city through fatwas, or Islamic rulings given by religious authority. ISIS became known for its brutal practices of public flogging, execution of civilians, and the enforcement of strict Islamic Sharia law, even on Christians.

“ISIS closed Jina after they broke its doors to prevent any civil gathering or organization that isn’t under its direct control,” Nofel said.

Despite these obstacles, activists who challenged the Assad regime began to confront ISIS. They started demonstrating again, but this time against Islamic battalions, including ISIS.

In July 2013, ISIS captured a man, who was whipped for trying to stop its militia from attacking the home of a Shia resident. “When we heard of the incident, more than 200 people demonstrated for hours in front of its office until they released him,” Nofel said.

When ISIS kidnapped activist Feras Al Haj Saleh on July 19, 2013, more than 300 people protested at the office of Ahrar Al Sham. “This was the largest demonstration against extremism in Raqqa,” Nofel said.

Other towns — mainly in the provinces of Aleppo and Idlib — have also witnessed major protests against ISIS. In January 2014, hundreds of Syrians demonstrated in Achrafieh. “Down with ISIS,” they chanted. On September 20, 2013, people in Achrafieh also launched a sit-in, in which children participated, called “only Syrians will free Syria.”

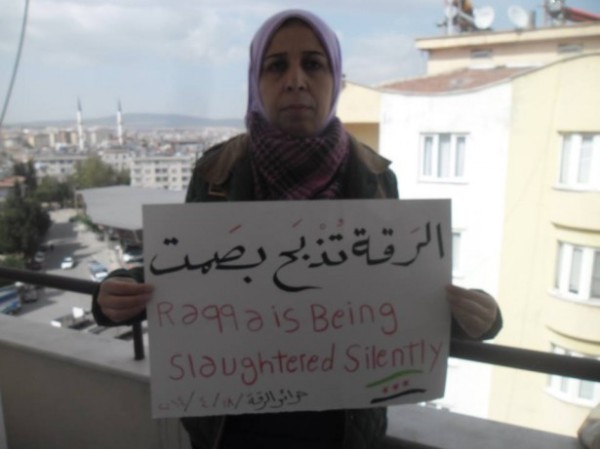

The campaign Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently was launched in April 2014 to expose the ruthless practices of ISIS with the support of locals who leaked the information under strict surveillance. The group established a Facebook page and Twitter account as an alternative media outlet to reveal ISIS’s crimes against civilians, which generated thousands of followers.

In May 2014, business people closed their shops and commercial offices in a general strike in Minbij. ISIS sent its militants to reopen the shops, but people began marching and asking ISIS to leave.

People in places like Sarakeb, a strategic town in Idlib that links Damascus and Aleppo and is known for its industrial facilities and agricultural production, including wheat and olive, have been organizing more demonstrations to face ISIS’s increased influence.

ISIS is trying to expand and establish an Islamic state in the province of Der el-Zor and other so-called liberated areas that are under the opposition’s control.

“The true motive is the economic resources of the city and its suburbs,” a member of the FSA said. People in such places have been demonstrating to prevent ISIS from fully controlling their neighborhoods.

Civil resistance was not limited to demonstrations, strikes and sit-ins. Independent media played a vital role in exposing atrocities committed by all aggressors. The independent Aleppo Media Center was established in October 2012 to report on news and nonviolence campaigns in Aleppo and its suburbs. The center continues to provide coverage of the revolution and uses online and social media to reach a wider audience.

Independent newspapers and magazines such as Inab Baladi (Local Grape), Souriatona (Our Syria), and Sada al-Sham (Damascus’s Echo), which proliferated after the Syrian uprising to cover the revolution and the regime’s crimes, are now covering ISIS’s atrocities.

Local Coordination Committees, a network of local groups established in 2012 across Syria to organize protests, support relief work, and report on the regime’s atrocities, have also been active in documenting and reporting on ISIS’s brutalities through social and online media.

ISIS used social media to publicize the execution of civilians to deter people from resisting. “Continuous shooting, public flogging and execution of activists have decreased civil activities to almost nothing in Raqqa now,” said a member of the FSA.

According to Al Arabi Al Jadeed, an online newspaper, ISIS has executed more than 1,600 people, including 53 women and 67 children, since they were established. In June 2014, ISIS publicly crucified two Alawites in Manbij, as people, including children, watched.

The barbaric killings by ISIS have terrified the population.“When people hear of ISIS, they either run away or surrender,” Zoia said.

When Nofel was protesting in 2013, ISIS was not as powerful and its leaders were concerned with public reaction. “But unfortunately not enough people have joined my effort in resisting and that’s why it grew stronger,” Nofel said.

The regime’s absence from liberated areas and the inability of the opposition to administer them gave ISIS an opportunity to take full control in places like Raqqa. Islamic authorities are resorted to because there are no alternatives in most of the liberated areas.

“People in towns under the threat of falling under ISIS’s control could be empowered and their civil activities could be supported,” Zoia said. “We can support defected judges and lawyers to build civil courts to counter Islamic authorities. We can also rebuild schools and support the local councils to provide better civil services to the population.”

From challenging Assad’s regime to facing ISIS, civil and nonviolent activities are still vigorous at the local level. “Civil resistance should be continued in places under the threat of ISIS’s control,” Nofel said. “Only Syrians can free Syria.”