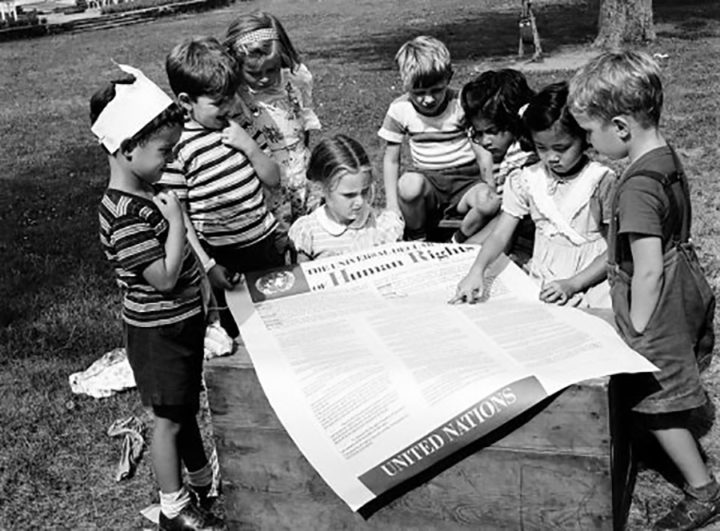

December 10, 2020 is the 72nd anniversary of the adoption of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The document is a powerful, and hopeful, testimony to the belief that all people on our planet should have access to fundamental human rights, including protection under the law, freedom of thought and expression, the right to an education, and the right to an adequate standard of living. It is difficult this year, however, to imagine a joyful celebration of this milestone event, given the worldwide challenges presented by the coronavirus pandemic. According to Feeding America, the largest hunger relief organization in the U.S., more than 50 million people will experience food insecurity this year in the US, the world’s wealthiest country. “Across Latin America and the Caribbean, millions of the most vulnerable students may not return to school,” said Bernt Aasen, UNICEF Regional Director for Latin America and the Caribbean. “For those without computers, without internet, or even without a place to study, learning from home has become a daunting challenge.”

The pandemic has become a magnifying glass that highlights the gap between the aspirations of the declaration itself and the situation experienced today by people on the ground. The main challenge for this declaration, as opposed to previous advancements like universal education or the abolition of slavery, is that, as strong as it is, it is not a legally binding document. It was created, instead, as a reference to be followed and applied country by country. But here is the question: how many countries have changed their own constitutions to adopt the principles in this document? How many international institutions have embraced this declaration? Very few.

For example, let’s look at Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Applying this article, many police department in the US would be in big trouble. Only 110 law enforcement officers nationwide1 have been charged with murder or manslaughter in an on-duty shooting — despite the fact that around 1,000 people are fatally shot by police annually, according to a database maintained by The Washington Post. Furthermore, only 42 officers have been convicted. And many of those convictions ended up being for a lesser offense — only five of these officers were convicted of murder (and did not have the conviction overturned). When will the U.S. Department of Justice be adopting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights?

Imagine if the World Trade Organization had applied the UDHR before it established trade agreements between countries; the world will be a very different place today. And if corporations and economic entities were to implement Article 23, we would in a very short time witness a sea of transformations for millions of people:

(1) Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favorable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

(2) Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

(3) Everyone who works has the right to just and favorable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

(4) Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

As for education, Massachusetts passed the first compulsory school law in 1852 and by 1918, all American children were required to attend at least elementary school. Currently, the City of New York spends 33% of its budget on education and is legally obliged to accommodate any children requesting to be enrolled. Similar policies were adopted in many countries around the world and today UNESCO, with 193 member states, is leading efforts towards Universal Education. It may be our largest success at implementing a Universal Human Right and has been a very interesting demonstration effect.

In light of the the challenges we are facing in a post-COVID world, perhaps Universal Basic Income (UBI) can be seen as the next human right to fight for. Just last week, World Food Program (WFP) chief David Beasley predicted that 2021 would likely be “the worst humanitarian crisis year since the beginning of the United Nations” 75 years ago, adding that, for a dozen countries, famine is “knocking on the door.” In our society, no one can live without economic resources, and yet most people don’t even have sufficient resources to look after themselves or their families. UBI would provide everyone with a minimum guaranteed income. Like the sentiment expressed in the UDHR, the basic tenet of UBI is that any economic system should be at the service of everyone’s wellbeing, and not the other way around.

Hopefully, the enormous necessities of this time will help us to realize that there is much more security in adopting the UDHR than in continuing to spend vast energy and resources on immoral military budgets. Will the White-West — the so-called “developed society”– have the necessary leadership to shrink its military budget and create a demonstration effect, as it did previously with education? It is not a question of creativity or new ideas, but rather a question of putting the human being as the central value and concern. May the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provide us with the roadmap to our first truly Human Society.