Closing Indian Point will speed action on climate change, not hamper it

By Marilyn Elie and Linda Pentz Gunter

Next spring, the last working nuclear reactor at the Indian Point Energy Center on the Hudson River, 30 miles from Manhattan, will power down. At least 20 million people in the 50-mile radius of the 40-year-old nuclear generator can sleep more soundly. Future generations will thank us for no longer producing high-level radioactive waste that will bedevil the country and our community for years to come.

But, as that April 30, 2021 Unit 3 closing date approaches, some have called for New York governor, Andrew Cuomo, to keep Indian Point open. (Unit 2 closed permanently on April 30, 2020. Unit 1 closed on October 31, 1974 due to serious technical failures.)

The first thing to note is that the governor has no legal authority to either close or open a nuclear reactor. And while the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) can order a reactor closed in case of danger, it cannot order the license holder to keep a reactor running. That’s a decision taken by the reactor owner, in this case, by Entergy, which owns the Indian Point plant.

In New York’s deregulated energy market, corporations close down generators that are not making a profit — and that is exactly what Entergy has done with all six of its nuclear reactors in the northeast. The company is retreating south, where they have a monopoly and do not have to worry about competition.

The chief — and really only — argument made in favor of keeping Indian Point running is the false notion that its output will automatically be replaced by natural gas, which is of course counterproductive to addressing the urgency of climate change.

Natural gas is still cheaper than nuclear power, but it’s not actually where things are going when reactors close (see California and Nebraska, both replacing closed reactors with renewables).

In fact, according to a recent analysis by Amory Lovins, it only happens for political reasons: “Replacing a closed nuclear plant with efficiency or renewables empirically takes only 1–3 years. If owners don’t give such advance notice — a common tactic to extort subsidies by making closure more disruptive — more natural gas might temporarily be burned, but then more than offset over the following years by the carbon-free substitutes.”

In other words, gas cannot compete in the long term with the rapidly falling price of renewables. Lovins contends that the gas infrastructure that is going in all over the country will eventually be a stranded asset by 2034 and a drain on the companies that are building them. The Rocky Mountain Institute concluded in a recent report that “the role of gas as a ‘bridge fuel’ is behind us.”

The advocates for keeping Indian Point open say they are concerned about what they see as loss of low carbon electricity that was generated at Indian Point around the clock. But it is a mistake to view nuclear as a carbon-saver.

Nuclear power is certainly not carbon-free, and arguably not even very low-carbon when looking at the entire cradle-to-grave fuel chain, essential when calculating the true carbon footprint of any fuel. For nuclear power this means from mining uranium to disposing of the high-level radioactive waste.

To that must also be added decommissioning, another high carbon-emitting phase in the nuclear fuel chain, and on which a shuttered Indian Point must now embark.

Decommissioning means cleaning up the property in a prompt, safe manner and returning it to a greenfield that can go back on the regular business tax rolls. Rapid decommissioning at Indian Point could take from 12 to 15 years or even longer but must be done safely and securely.

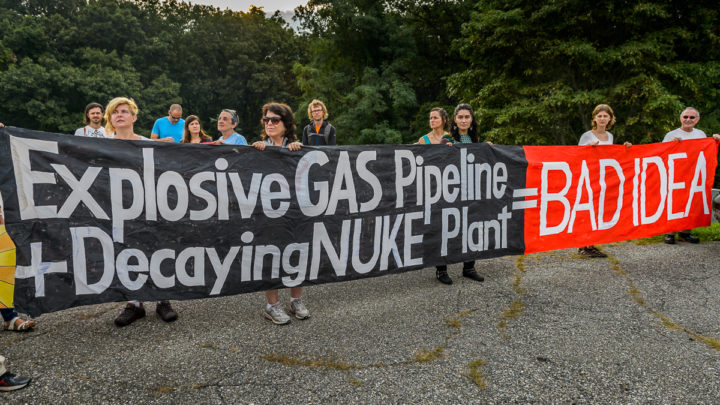

But at Indian Point there’s another challenge: The AIM gas pipeline, which traverses the Indian Point nuclear site, presents the threat of a possible rupture and explosion which could engulf the spent fuel pool. And while the NRC must supervise anything that is radioactive during decommissioning, the agency has no authority over the pipeline.

Instead, it is Holtec, the company that is in line to do the decommissioning, that will take the lead for the rest of the work, and therein lies yet another problem. Holtec is a big international corporation based in New Jersey that, as described by ProPublica, “won the second-largest tax break in New Jersey history” and then “gave a false answer about being prohibited from working with a federal agency in sworn statements made to win $260 million in taxpayer assistance for a new plant in Camden.” Holtec’s Canadian partner, SNC-Lavalin, is currently barred from any contracts with World Bank projects until 2023 due to bribery and corruption.

Decommissioning Indian Point is a mammoth undertaking, and the fact that the company chosen to do it has a track record of fraud is worrisome. To ensure that New York State taxpayers are not stuck with a big bill when the Decommissioning Trust Fund runs out, a New York State Decommissioning Oversight Board needs to be established. Its members must represent the wide range of people in the community, with the Village of Buchanan, where the reactors are located, given a prominent seat at the table. This community will suffer the most financially from the closure as they lose a significant part of their tax budget.

Other agencies such as the New York Department of Environmental Control and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency will also be involved. That could mean that some of the buildings may remain on the property, since they do not fall into existing decommissioning criteria. The irradiated fuel rods will remain as current law requires but will be put in dry cask storage. Entergy estimates that when all of the fuel rods are in dry casks they will take up the area of approximately two football fields.

Eventually, that waste could leave the site. Again, this involves challenges and risks, as there is nothing safe or simple about any phase of the nuclear fuel chain.

Transporting high-level radioactive waste on our roads, rails and waterways, through villages, towns and neighborhoods, is asking for trouble. Accidents, fires or even deliberate attacks are all possibilities.

At present, the only two destinations under consideration to take this waste, both fiercely opposed locally, are so-called interim sites in Texas and New Mexico. Both sites are also facing legal challenges as the Nuclear Waste Policy Act currently prohibits the establishment of an interim nuclear dump until a permanent location is available. Uncoincidentally, Holtec is the owner of the New Mexico dumpsite and is hard at work trying to change the law so that the company can transport high level radioactive waste there.

Sending radioactive waste to an “interim” site would of course necessitate moving the waste again to permanent storage at a later date, when the waste casks would be older and likely damaged.

Communities around Indian Point should think very hard about this prospect. After all, sending our high-level radioactive waste to contaminate another community that does not want it is undemocratic and some would say immoral.

New York is poised to make great strides in decarbonizing the state’s economy through the recently passed Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act. People in different regions of the state are meeting now and figuring out how to achieve the high goals set by this law. Community groups have been formed and are in the process of reaching out to others. Hopefully many New Yorkers will look for an opportunity to participate. Things must change. The regular and accustomed path of business as usual using fossil fuels will not suffice if we are to hand over a livable planet to future generations.

Marilyn Elie is a member of the Indian Point Safe Energy Coalition. Linda Pentz Gunter is the international specialist at Beyond Nuclear and writes for and edits Beyond Nuclear International.

Headline photo by Erik McGregor.