? Professor Deirdre Heddon and Dr Misha Myers explain how their Walking Library functions as a public artwork connecting people with places and writing.

The Walking Library is simply a library filled with books suggested as good to take on a walk.

In 2012, we created our first Walking Library, a commission for Sideways, an ecologically-oriented, pedestrian festival traversing the Flanders region of Belgium.

To make a donation to support the next Timber festival, visit JustGiving.

Sideways aimed to find and walk back into existence the region’s ‘slow paths’ – a mesh of footpaths that offer alternative ways of getting from A to B without the need of a car. For that first Walking Library we posed a simple question: What book would you carry on a walk?

Readers

From more than 200 suggestions, we selected about 90 books and took them out on our daily walks, which, over the course of the month, added up to 334 km on foot.

Our stock was diverse, ranging from books about walking – fictional, biographical, historical – to guidebooks on flora and fauna, and books about treading more gently on the earth.

We invited people to tell us why they made their suggestion, and we added this information to library card’s that we placed in pockets inside each book. This made the library more personal, creating invisible networks of affinity between readers.

Together

As we walked and read together, we discovered that the books became our companions, guides, teachers, and interlocutors. Our encounters with both books and landscapes were enriched by putting them in dialogue with each other. We saw new things on the page and in the environment.

We have made a number of Walking Libraries since our first experiment of walking with books in 2012: each with a different focus and prompting a different set of questions, including a Walking Library for Women Walking and a Walking Library for a Wild City.

The Walking Library functions as a public artwork connecting people with places and writing.

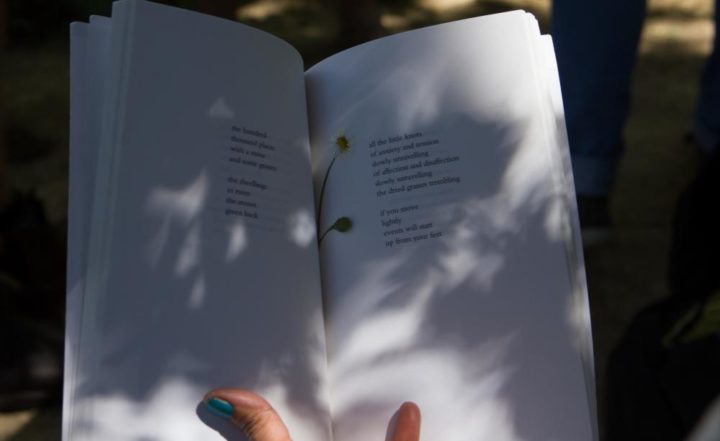

We invite participants to select and carry a book from our library and join us on a walk, in the company of about 15 other books and for a duration of anything between 90 minutes and a full day. Prompted by the landscapes through which we walk, we pause together to share aloud extracts from the books we carry.

Forest

We have found the book to be a magnificent ‘glue’, bringing people together gently in the creation of a convivial space for knowledge sharing, akin perhaps to a friendly and healthy mobile reading room.

Books and walking share the capacity for inspiring simultaneously attentiveness and escape, and stillness and mobility. We read and walk slowly, listening, seeing, learning and paying closer attention.

Our most recent library is a Walking Library for Forest Walks, commissioned for the National Forest. To gather suggestions of books for this new library we asked:

What book would help you see the forest for the trees? What book would provide seeds for thought and future forests? What leaves would you want to turn and share? What forest stories stretch both legs and minds?

We had planned to take this library on its inaugural walk as part of National Forest Walking Festival in May and to bring it to the Timber Festival in July. When COVID-19 lockdown restrictions came into place, we added a new question: Which book transports you to the forest without leaving home?

Virtual

We have received approximately 100 suggestions. Though not able yet to take the library into the forest, we have created some virtual forest walks, adapting the principles of the Walking Library to these new circumstances.

The forest remains the prompt for finding and sharing synergies between texts and place. Working with photographs taken in the National Forest, including many by local resident Hazel McDowell, we sought to virtually locate extracts from books within apt environments.

The photographs provided imaginative illustration of the books and the books brought to life something of the rich forest environment. After all, books have always been mobile devices offering portals to virtual worlds and when you hold a paper book, you hold a tree.

Picture this: an old and somewhat wizened tree, standing large, proud and resolute against a background of sky.

“‘Ah, when it was quite a small tree,’ he said, ‘and I was a little boy, I thought one day of chopping it off with my hook to make a clothes-line prop with. But I put off doing it. And at least it got too big, and how ‘tis my enemy, and will be the death of me. Little did I think, when I let that sapling stay, that a time would come when it would torment me, and dash me to my grave.’”

Astonishment

These are words from Thomas Hardy’s The Woodlanders, spoken by the elderly and fearful John South, as he looks out of the window from his sickbed onto an elm. This book was suggested by Julie Attard, who wrote:

“Set in a remote woodland village, the tangled lives and struggles of its inhabitants are played out against, and are reflected by, the trees surrounding them. In the novel, trees are almost sentient and characters in their own right. Perspectives shift between scientific and folkloric understandings of the environment. In a sense Hardy asks a question that we are still asking today: what does it mean to be connected to nature?”

Or picture this: a large, green, bushy-topped tree, with a thick trunk, a strange tree-formation that seems to have created a tunnel out of branches, a tree that seems to fizz and froth white flowers.

“‘Wisha-wisha-wisha-wisha,’ said the trees.

‘Come on,’ said Joe impatiently. ‘Let’s go to the Faraway Tree.’

They all went on – and soon came to the mysterious magic tree. Rick stared at in great astonishment.

‘Wow, it’s simply ENORMOUS!’ he said. ‘I’ve never seen such a big tree in my life. And you can’t possibly see the top. Goodness me! What kind of tree is it? It’s got oak leaves, and yet doesn’t really seem like an oak.’

‘It’s a funny tree,’ said Beth. ‘It may grow acorns and oak leaves for a little way – and then suddenly you notice that it’s growing plums. Then another day it may grow apples or pears. You just never know. But it’s all very exciting.’”

The Magic Faraway Tree, by Enid Blyton, was suggested by Blue Bradley Cole simply because, “It’s my favourite book in the whole world”.

Walks

Though not able to physically visit the National Forest and walk with the library at the Timber festival, we have ventured into rich imaginary alternatives, grateful for the convivial company of authors and the readers who recommended them.

Creating short films which intersperse readings with photographs, we have felt connected in multiple ways with forests and people. This virtual forest has been enchanting, magical, forbidding, generous, vital, and threatened.

We look forward to bringing the library to next year’s Timber, and walking with it through the forest, combining the imaginative and real, just as all walks and forests do. Once upon a time…

This Author

Professor Deirdre Heddon holds the James Arnott Chair in Drama at the University of Glasgow. Dr Misha Myers is Senior Lecturer and course director of Creative Arts at Deakin University.

Andrew Weatherall works at the National School of Forestry, University of Cumbria. Jo Maker is the Timber Festival coordinator, The National Forest Company. They are together the guest editors of this Special Collection in The Ecologist. To make a donation to support the next Timber festival, visit JustGiving.