By Jhon Sánchez

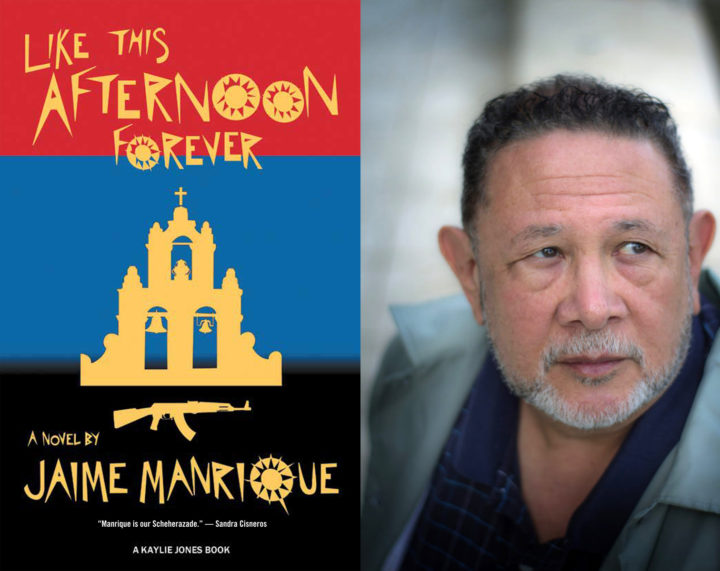

Jaime Manrique lives around the corner of the AIDS monument in the West Village. As soon as I entered his apartment, I saw the poster of the book-cover of “No One Writes to the Colonel” by Gabriel García Márquez, illustrated with a large fighting cock. Isabela, an Australian cockatiel greeted me with a loud screech from the kitchen. We had coffee, Italian cookies and talked about “Like This Afternoon Forever”, title of Manrique’s most recent publication.

I have, of course, a series of questions, so I asked him, “Maestro, congratulations again. The events that give rise to the novel also have a profound impact on my life. I even wrote a poem about it. Tell us how you came across the story and when you decided to write a novel about it.” He thought about it and said, “Can I ask you a question? Why the events that give rise to the novel also have a profound impact on your life.” Like Manrique himself, I also read the article in El Tiempo, the Colombian newspaper. Two Catholic priests in love hired a hitman after finding out that one of them was HIV positive. The news brought me to tears for my friends who died of AIDS and for the ones who took the holy vows and hid their sexual orientation. I told Jaime that I even wrote a poem about it.

Jaime paused and closed his eyes to answer, “I became fascinated by it, and I started to imagine the lives of these two men.”

In 2012, Jaime visited the small town of Soacha in Colombia where Father Riatiga had his parish. In a bakery, he talked to the owner, a woman who met the priest. “I felt admiration for him.” He was referring to Father Riatiga’s ability to start all the social programs he started as it’s told in the novel.

We continued with the interview.

JS: We found two priests and two different perceptions of faith. Can you comment on that?

JM: I created two characters who were very different. One would be a conventional believer, conservative, and the other skeptical who almost didn’t believe in God. I developed this dialectical method of one who believes versus the one who doesn’t. This gives the novel a dramatic tension.

JS: This story could be a good mystery novel, don’t you think? How would you describe the style of narration, and what led you to choose it?

JM: The writing of the novel changed. When I began to write the novel, each character had a voice, and they alternated. But I realized that the voice didn’t seem real, so I switched to a third-person point of view and to have an omniscient narrator. About the suspense novel, I didn’t think about it. At some point, I felt the pulse of the story and I tried to follow, but it wasn’t something I planned.

JS: Both characters, Ignacio and Lucas, shared similar backgrounds in terms of class. Do you think that gay people from the lower social classes in Colombia have more difficulties expressing their sexual preferences?

JM: I don’t live in Colombia. I have lived in NY for the last forty years. When I moved here, it was hard to be gay in Colombia. Now, it’s different. There is a large demographic of openly gay people. I don’t know whether being working class makes it more difficult. Nowadays, we can see gay people on Television, on the Internet. But if it is less acceptable to be gay for the working class, I think is because it has less access to education.

JS: Your novel is about the military conflict in Colombia during the ’90s and 2000s. One of your characters says, for example, “Here in Facatativá, we’re so close to Bogotá that it’s almost as if the war is happening in a foreign country.” What does this tell us about the urban class in Colombia? How do we perceive the war?

JM: The war in Colombia changed throughout the years and more with the peace process. But most of the conflict was felt more acutely in the countryside than in the cities. People who live in the cities weren’t impacted as much with that kind of war. The conflict in Colombia was more rural than urban. In the cities, there is more investment in law and order that makes it harder for the war to come to them.

JS: Ruben Dario Acevedo, Director of the National Center for the Memory, refuses to acknowledge the existence of an armed conflict in Colombia. What are your comments on that?

JM: He must be living on another planet. I don’t know how anyone who lived in Colombia can say that about a conflict that has affected so many people. Politicians often twist language to obscure a very clear historical process. They don’t want to admit it because it’s a denial of reality for nationalistic reasons. Some people said, “Oh, Colombia is wonderful. It’s perfect. It’s not dangerous. Nothing bad really ever happens, but it’s very rare. It’s an attitude of denial that refuses to acknowledge the reality of the country. Maybe, it’s part of that. Hundreds of thousands have died. How can they deny that? If the government denies it, do we have to buy it? It’s historical fact; it has been widely documented.

JS: A photograph that depicted the massacre of twenty-five boys in Putumayo haunted Ignacio during his life. I think for many Colombians, those scenes haunted us as well. How can we forgive? Do you believe Ignacio would be able to forgive such atrocities during a peace process? Will we be able to liberate our psyches from those images?

JM: A brother of mine, on my father’s side, was shot fifty times. He died almost twenty-five years ago. My family in Santa Marta talks about him every day, as if it happened yesterday. I became very impatient with their unrelenting grieving. He had been killed a long time ago. Surely, I thought, they should have gone already through the process. But I realized that I didn’t have the right to judge them. People grieve, and if they want to do it the rest of their lives, they have that right. I don’t know if it’s possible to forgive those things, those massacres. It would be like asking the survivors of the holocaust to forget. It’s not so easy. We must go on with our lives, but if people are attached to traumatic events of the past, we don’t have the right to judge them.

JS: One of your characters says, “Colombian people are not charitable by nature. Because of the oppression in which we’ve lived, we have become cannibals of other Colombians.” This is a very harsh judgment about Colombian people, don’t you think? What’s your assessment of that?

JM: Colombian history, from the time of the arrival of the Europeans, has been a constant bloodshed. In all my novels, Our Lives are the Rivers or El Cadáver de Papá, for example, there is always that perception that people are not charitable. Certainly, most members of the upper classes show little empathy for the people in need. Colombians tend to be envious of people who do well. If someone is successful or has a good job, they feel that something has been denied to them. If an artist is recognized around the world, in Colombia, they are criticized, dismissed. It’s part of the national psyche: Many Colombians resent that life may be kinder to other people. This was probably what I meant to say, but I like how it comes out because it sounds very dramatic.

JS: Can you explain the Falsos Positivos to us? While writing the book, did you consider that the two priests were actually murdered as a result of their vocal denunciation of the Falsos Positivos?

JM: Greed seems to be the force behind the False Positives. The government wanted to give the impression that it was winning the war. That’s why they promoted the lie that people were killed in battle when, in reality, they were innocent civilians. There was a moment in the late 90s when the guerrillas were getting closer to the cities, and people were kidnapped everywhere. Maybe the government wanted to show they were still in control. It was a way of staging reality. About the two priests, I couldn’t say with certainty that they were murdered because of their activism. That would need further research, which I couldn’t conduct from New York. But some people in Soacha say that the two priests were killed by the government because Father Riatiga had denounced the Falsos Positivos. Do I believe it? I don’t know. But why not? It’s like many other atrocities that have happened in the nation.

JS: How was the book received in Colombia? Has the Catholic Church said something about it?

JM: I went to Colombia and granted some interviews, and I returned here. The reception was fine; but there was one interviewer who asked me, ‘Is this novel about poverty?’ as if it was not an acceptable subject. But the reviews that came out were very positive, and the people I heard from liked the novel. There was some noise at the beginning and afterward silence. When a book is received critically with silence, it’s hard for readers to find out about the book.

I congratulated Jaime not only on the novel but also because its publication celebrates his 70th birthday. We talked about his next project, and his eyes glided, looking at the rooster on the cover of No One Writes to The Colonel. “I have it there because my next novel is about a fighting cock and a boy. My father had a line of roosters that was famous in the Caribbean.”

Jaime Manrique is a Colombian-born novelist, poet, essayist, and translator who writes both in English and Spanish, and whose work has been translated into fifteen languages. Among his publications in English are the novels Colombian Gold, Latin Moon in Manhattan, Twilight at the Equator, Our Lives Are the Rivers, and Cervantes Street; he has also published the memoir Eminent Maricones: Arenas, Lorca, Puig, and Me. His honors include Colombia’s National Poetry Award, a 2007 International Latino Book Award (Best Novel, Historical Fiction), and a Guggenheim Fellowship. He is a distinguished lecturer in the Department of Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures at the City College of New York. Like This Afternoon Forever is his latest novel.

Jhon Sánchez: A Colombian born, Mr. Sánchez, arrived in NYC seeking political asylum where he is now a lawyer. His short stories are available in Midway Journal, The Meadow, Newfound, Fiction on the Web, among others. In February, Teleport published his short story ‘Handy.’ The DeDramafi, was published on The Write Launch, and Storylandia will reprint it in issue 36. He was awarded the Horned Dorset Colony for 2018 and the Byrdcliffe Artist Residence Program for 2019. In 2021, New Lit Salon Press will publish his collection Enjoy Pleasurable Death and Other Stories that Will Kill You. For updates, please visit the Facebook page @WriterJhon