By Sarah Freeman-Woolpert and Arnie Alpert

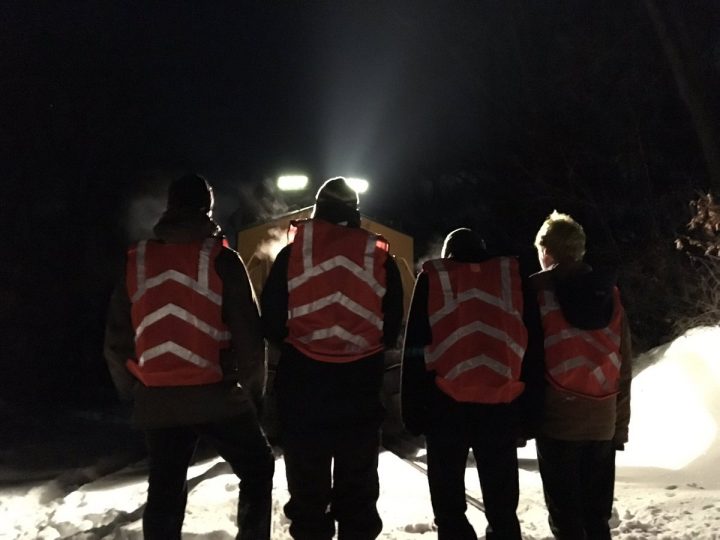

Under cover of darkness, dozens of climate activists snuck into the forest in the small town of Harvard, Massachusetts. The air was buzzing with nervous excitement as the group filed along a dirt path next to the railroad tracks, carrying heavy metal scaffolding. After half a mile of walking, the group set up camp and assembled the scaffolding into a 16-foot-tall metal structure above the train tracks.

Once the scaffolding was secured in place, the group formed a circle and joined hands. One of the activists announced that he had just placed a call to the railway’s emergency number, alerting the dispatcher that there were people and a metal structure on the tracks. Four people were stationed a ways ahead, waving red flags to make sure the coal train would stop. And stop it did — waiting several costly hours for police to arrive and arrest the four activists who had climbed onto the scaffolding and refused to come down.

This blockade, which lasted through the night on Jan. 2, was just the latest action for a coalition of regional climate groups and activists calling themselves the #NoCoalNoGas campaign. With the aim of shutting down fossil fuel infrastructure — starting with Merrimack Station, New England’s last coal-fired power plant without a shutdown date — the campaign has been leading actions across Massachusetts and New Hampshire since August.

As the blockades have surged in recent months, so too has the campaign. By escalating from symbolic actions to obstructing Merrimack Station’s ability to operate — leading to dozens of arrests in the process — the #NoCoalNoGas campaign is mounting the most serious challenge to the plant since it opened in Bow, New Hampshire in 1960.

“Part of what we’re trying to do is to show that burning coal at this stage is completely unacceptable and won’t be tolerated,” said Tim DeChristopher, one of the activists arrested at the Harvard blockade. “Coal trains can’t roll through our communities anymore without being impeded.”

DeChristopher’s group, the Climate Disobedience Center, or CDC, helped form the campaign, collaborating with 350 New Hampshire Action and a regional coalition of other climate action groups and individuals, including many first-time activists.

From thoroughly researching and identifying a vulnerable target to prioritizing the process of community-building among participants, the #NoCoalNoGas campaign is a strong example of how to develop an effective strategy, while also creating an inclusive environment for new activists to join. Building on the growing sense of urgency to address the climate crisis, organizers have harnessed public outrage into action.

“A lot of people even in the town [of Bow, New Hampshire] itself don’t know we’re still burning coal in New England, much less in their own community,” said Emma Schoenberg, a nonviolent action trainer with the CDC. “We started really thinking about ways in which we can bring awareness to the fact that this coal plant exists, and to eventually shut it down with a really prominent goal of building community.”

The campaign’s initial success at mobilizing large numbers of participants has led journalists and older activists to draw parallels with the Clamshell Alliance campaign of the 1970s, which fought to stop construction of the Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant in New Hampshire. In 1977, during the largest of several acts of mass civil disobedience, 1,415 people were arrested while occupying the construction site. While the Clamshell Alliance wasn’t able to stop Seabrook, it sparked a national anti-nuclear movement that deserves credit for largely shutting down further nuclear construction, as well as inspiring a greater public understanding of nonviolent direct action.

Today, the #NoCoalNoGas campaign could do for coal what Clamshell did for nuclear energy: build a blueprint for shutting down a dangerous industry through coordinated direct action.

From #BucketByBucket to #TrainByTrain

Although many participants in the #NoCoalNoGas campaign are new to civil disobedience, the campaign’s core organizers are veterans of nonviolent struggle. DeChristopher, who is a co-founder of the CDC, famously posed as a bidder at an oil and gas auction in 2008 to protest the sale of public lands — a stunt that landed him in prison for 21 months.

It thus comes as no surprise that the #NoCoalNoGas campaign began with a bit of surreptitious action, when a core group of activists decided to scout out the coal plant’s layout firsthand. In August, five of them walked straight onto the grounds of the power plant to see it for themselves.

“After having a good look around, we went in and talked with some of the managers of the plant,” DeChristopher said. “We explained to them that we need to shut this plant down for the sake of the climate and our survival. They were pretty surprised that we were able to just walk right into the plant.”

On August 17, the campaign launched its first action when eight activists removed over 500 pounds of coal in buckets from the power station grounds. Three days later, they dumped buckets of coal in front of the New Hampshire State House in Concord, New Hampshire and told the media they were laying the responsibility for ending coal usage on the government’s doorstep.

A month later, on Sept. 28, dozens of people dressed in white tyvek suits and carrying plastic buckets tried to approach the coal pile at Merrimack Station. Met by police in riot gear, 67 were arrested and charged with criminal trespassing. They sang and drummed on buckets throughout the action, while 300 more rallied in the field across the street from the plant. According to the organizers, it was one of the largest environmental civil disobedience actions in New England since the Clamshell actions at Seabrook 40 years ago.

Seventy-six-year-old Espahbad Dodd was one of the bucket-bearing activists arrested that day. Having never taken such a risk before, he noted, “It just got to the point where it was time. I figured I don’t have grandchildren, but I have lots of friends that do. I don’t want to think about any responsibility I have for not leaving them a world in which they can live.”

The next major action took place two months later in early December. Shifting from #BucketByBucket to a rallying cry of #TrainByTrain, activists began blockading railroad tracks as trains carried shipments of coal through New England to Merrimack Station. The first blockades happened during the night of Dec. 7 and into the next day. Over 100 activists blockaded the train tracks at three different points along the route, beginning in Worcester and Ayer, Massachusetts and culminating with a third blockade in Hooksett, New Hampshire. The coal train was delayed for several hours, resulting in 24 arrests on trespassing charges. Two people were further charged with resisting arrest after refusing to come down from a railroad bridge.

Activists attempted to blockade the tracks again on Dec. 16 in West Boylston, Massachusetts. However, despite calling the emergency dispatcher and waving red flags to signal the conductor, the coal train did not stop, and almost two dozen activists had to jump out of the way as the train barreled towards them.

The group remained undeterred, organizing another train blockade Dec. 28, when over 20 people in Worcester stood across the tracks. Ten were ultimately arrested, setting the stage for the scaffolding blockade in Harvard on Jan. 2./p>

“If [the Harvard blockade] had been an isolated action, then maybe it would feel like we didn’t accomplish much,” said Cody Pajic, who was arrested at the blockade on Jan. 2. “But #NoCoalNoGas is a long-term strategic campaign, and when Bow finally shuts down, we’ll know that the train blockades were part of the path that got us there.”

These train blockades embody one of the campaign’s guiding principles: that ordinary people can take matters into their own hands to disrupt fossil fuel infrastructure and address the climate emergency.

“We can stop these trains fairly easily,” DeChristopher said. “It’s a very simple thing to do, and it needs to become commonplace.

Developing strategy and an inclusive campaign culture

Participants like Barbara Peterson, who has long studied nonviolent direct action, have emphasized the campaign’s strategic sophistication as a key reason for getting involved. From thoroughly researching a target to providing intensive training in nonviolent direct action and regularly evaluating previous actions, #NoCoalNoGas has been intentional about shaping a campaign that is smart and effective.

“We do a process of evaluation of the tactic after we’ve used it,” Schoenberg said. “For me, it’s important to ask, ‘Did this meet our goals? Did our strategy shift from the data and information we received? Does a different tactic make sense? Or do our people need rest?’”

Asking these questions allows activists to shift focus from civil disobedience to community-building when needed. For example, in the coming weeks the campaign may place more emphasis on supporting activists facing court proceedings than conducting direct actions. In this way they would also be able to work on advancing the use and acceptance of the “climate necessity defense” — a legal argument that would allow activists to explain their unlawful actions as being for the greater good.

Nevertheless, organizers are clear on the campaign’s three goals: The first is to develop community and ownership of the campaign among participants as they put their bodies on the line; the second is to show people in New England and around the country that it is possible to shut down a plant like Merrimack Station with direct action; and the third is to shut down the plant itself, while also preventing the plant from being converted into a natural gas facility. The community-building aspect is considered more important for building power in the long-term than simply shutting down the plant.

“We are building Dumbledore’s Army,” said CDC co-founder Jay O’Hara. “We will grow in deep relationship with one another in a movement network across the region, and therefore we will grow in power. Once we are done with [Merrimack Station], we will move onto the next thing.”

O’Hara said the campaign embraces an approach of “emergent strategy,” which allows for a flexible, ever-evolving series of actions that are not centrally planned and imposed.

“We don’t get together and write a strategic plan that has these predetermined peak moments of escalation, timelines and how we’re going to mobilize various resources,” he explained. “It’s not that we don’t think about those things, but we don’t start from there, because when we start from there we start to think of human beings as the pieces we’re trying to plug into our plan. From my perspective, that is the central problem of the domination system we’re trying to get out from underneath.”

Peterson said that despite the challenges of doing direct actions, being a participant in the campaign feels deeply purposeful and important.

“I suppose everyone’s different, but for me it’s not fun getting arrested,” she said. “It’s not fun going against the system. It’s frightening, it’s incredibly inconvenient — you have to sleep out overnight. I’m not woodsy. I’m not a camper. We do it because we can’t not do it.”

Part of the campaign’s strength comes from this approach of building solidarity and joy among participants. One way activists are doing this is by cultivating a culture of singing into their organizing and direct actions.

“We haven’t seen that in many movements since the civil rights movement, when black spirituals that people sang at home and in church were brought into social justice spaces,” Schoenberg said. “That seems like a sign that we are really building a transformational movement when people sing together, because that comes from people’s homes.”

Building a regional movement against coal power

While three coal-fired power plants still remain in New England, one (Bridgeport Station in Connecticut) is scheduled to be closed in 2021 and the other (Schiller Station in New Hampshire) has been partially converted to run on wood chips. This has made Merrimack Station — the only fully coal-fired power plant without a shutdown date — the target of #NoCoalNoGas.

What’s more, Merrimack Station is also quickly becoming obsolete. Owned by Granite Shore Power, a partnership between two Connecticut-based companies, it operates infrequently under the direction of ISO New England, which manages the regional power grid.

“[Merrimack Station] is vulnerable because it’s unnecessary,” DeChristopher said. “If we can give a bit of an extra push in terms of making it more inconvenient and expensive to run that plant, we can put it over the edge in shutting it down.”

The plant also receives millions of dollars in “capacity payments” from New England rate-payers even when it’s not operating, so it can stay prepared to produce energy if needed.

“The fossil fuel industry is working up agreements with companies like ISO New England, saying ‘You’re gonna need us. What if there’s a cold snap?’” Schoenberg said. “Pushing back on that narrative is going to be critical.”

New England operates an auction-style energy grid, in which distributors purchase that energy from producers. Generating negative media attention and public outrage against the Merrimack Station and coal production could dissuade distributors from purchasing energy from the plant, organizers said.

The #NoCoalNoGas campaign builds on a longer history of climate activism in the region, including a number of other campaigns to shut down coal plants in New England. One such effort took place back in 2013 with the Lobster Boat Blockade, during which two environmental activists, including the CDC’s Jay O’Hara, blocked a freighter from delivering a shipment of coal to the Brayton Point Power Station in Massachusetts. Brayton Point was the largest coal-fired power plant in New England until it shut down in 2017.

In an effort to continue building momentum to drive coal out of New England, Quakers the 2015 “Pipeline Pilgrimage” with a group of young Quakers as part of the Young Adult Friends Climate Working Group. They marched for 12 days along the 150-mile route of a fracked-gas pipeline that was proposed to run through Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

In 2017, Quakers led another pilgrimage from the Schiller power plant in Portsmouth, New Hampshire to Merrimack Station, 50 miles away. Another plant, the Pilgrim nuclear power plant in Plymouth, Massachusetts was shut down in 2019 after local outrage at the poor maintenance and dangerous conditions of the plant.

The #NoCoalNoGas campaign is part of a larger regional movement to shut down fossil fuel infrastructure, and has developed stronger linkages between various environmental campaigns in New England, including the campaign opposing the natural gas compressor station in Weymouth, Massachusetts and protests against JPMorgan Chase Bank, which has underwritten billions of dollars of funding for new coal-fired power plants.

“We are building a regional New England identity,” Schoenberg said. “That’s the same level at which our energy grid operates. Each state is trying to pass a deal around the climate emergency in their own way, and we’re building a network of people helping each other with resources and skills.”

The campaign may have lasting ripple effects on New England’s energy grid. State officials in Connecticut say the state may withdraw from the regional energy grid and reconsider pro-natural gas policies. Meanwhile, Massachusetts lawmakers are discussing the possibility of implementing carbon pricing. As the #NoCoalNoGas campaign continues, activists will use the growing regional network to apply pressure on key actors, from elected officials to presidential candidates to corporate executives.

Lessons 50 years after Seabrook

It’s not hard to see the Seabrook protests as ancestors of the campaign to shut down Merrimack Station. Both campaigns showed commitment to nonviolence, used blockades and occupations, employed creative expression, devoted energy to nonviolent action training, and organized participants into affinity groups.

Both campaigns also understood the corporate connection. The Clamshell protesters knew they were up against New Hampshire’s largest electric utility company, Public Service Co. of New Hampshire, with ties to a web of local and regional financial interests. Their actions included occupying the board room of a major Boston bank and a blockade of the New York Stock Exchange in 1979 on the 50th anniversary of the market crash.

Yet, as much as the climate activists of today are taking lessons from Seabrook, they are also aiming to forge something radically new.

“What makes something powerful is not to try and re-inhabit or re-deploy the tactics of a previous generation,” O’Hara said. “What makes something powerful is the underlying spirit that infuses the group taking action.”

As New England’s climate activists gear up for this next year, shutting down the region’s last coal-fired power plant is only one step along the way. Step by step, bucket by bucket, and train by train, a multigenerational movement is growing to tackle the climate crisis — and the campaign to close Merrimack Station is only the beginning.