Palestinian citizens of Israel are intensifying their fight for equality. The right-wing has spent the last decade doing everything in its power to stop them.

When the Knesset passed the Jewish Nation-State Law on July 19, 2018, there was an outpouring of concern for the Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel, who make up a fifth of the state’s population with 1.8 million people. The prevailing narrative was that the new Basic Law — which will serve as a constitutional anchor for Israel’s legal system — would “officially turn non-Jews into second-class citizens.” Large segments of the community bought into the narrative, too. Druze citizens, who are conscripted into the Israeli army, decried the government’s “betrayal” of their loyalty to the state. The Arab leadership in Israel, including the Joint List, High Follow-Up Committee, and civil society organizations, publicly campaigned for the law’s revocation.

The Jewish Nation-State Law is the crown jewel of the Israeli right’s decade-long power streak. Having transfused Revisionist Zionism into the Israeli mainstream, and finding like-minded global allies to support its mission, the right-wing establishment no longer feels the need to uphold the Zionist left’s democratic pretenses toward its “minority” citizens: Jewish supremacism is now the unequivocal and unapologetic law of the land. This is hardly the beginning of legalized racism in Israel — Palestinian citizens have known military rule, land expropriations, unfair budgeting, and many more discriminatory policies since 1948 — but the dangers it foreshadows are no less severe.

The past decade for Palestinian citizens has been dominated by the Israeli right’s unbridled assaults on their civil rights. Yet these attacks are not just a reflection of the right’s strength; if anything, they expose its biggest weakness. While the right’s ambitions are largely driven by its obsessive desire to build a “Greater Israel” from the river to the sea, it is also deeply defined, quite ironically, by its inconsolable fear of the Palestinians who share Israeli citizenship and live within the state’s 1948 borders.

This fear, which afflicts the Zionist left as much as the right, has consumed Israeli politics and lawmaking in recent years. During the 1990s, Palestinian citizens of Israel underwent a political, social, and cultural revival to assert their voice in the context of the Oslo Accords. While many were swept by the hopeful atmosphere of the time, they were also concerned that a two-state arrangement — which was being negotiated between a Jewish-Israeli government and a Palestinian leadership focused on the West Bank and Gaza — could marginalize, if not jeopardize, their own existence.

Using Israeli and international institutions to their advantage, Palestinian citizens began making small but significant strides in demanding their rights as a “national minority.” Even after the traumatic events of October 2000 — when police killed 13 Palestinians in Israel and wounded hundreds more in protests during the Second Intifada — the community in 2006 put forward a “future vision,” including a draft constitution, to imagine a shared state (alongside a Palestinian state) based on equality and self-determination for both peoples.

Israelis were terrified. “Equality,” as far as they were concerned, meant the demise of the Jewish state and a reckoning with their colonial past. And so, when the Netanyahu-led government came to power in 2009, Palestinian citizens were immediately put in the crosshairs. A slew of legislation was subsequently enacted to reverse many of the Palestinian community’s advancements, ensuring that their subjugation was permanently pinned down in law and not just in policy.

The scale of the government’s campaign was unprecedented. When more Arab families tried to buy homes outside of their overcrowded towns, admissions committees were empowered to reject them on the grounds that the families did not fit with the villages’ “social and cultural fabric.” When students organized vigils to commemorate the Nakba on campuses, universities were threatened with funding cuts if they allowed the events to take place. When Palestinian activists called for boycotts of institutions involved in the occupation, Israelis were invited to sue them in court. The list keeps growing.

The past 10 years have thus trapped Palestinian citizens in a paradoxical position. On the one hand, the community has never been stronger. They enjoy better standards of living, access to higher education, and global communication technologies. They are more politically conscious, connected to their Palestinian brethren, and assertive of their national history and culture. And yet, Palestinian citizens are also at one of their weakest points in recent memory. They are ailed by local violence, frustrated by underfunded services, and fatigued by daily racism. Home demolitions are rising, civil rights are shrinking, and there is no political consensus on how to counter them.

It is amidst these daunting realities, and a disillusionment with the old ways of “minority” politics, that new forms of leadership and resistance are emerging among Palestinian citizens. Youth-led grassroots activism, bolstered by the social media age, is re-centering the community’s place within the wider Palestinian cause. This activism was witnessed against the Prawer Plan in 2013, during protests of the government’s campaign to forcibly displace thousands of Bedouin citizens in the Naqab (a campaign that continues to this day). It came out in force during Operation Protective Edge in 2014, with protestors facing off repressive Israeli police in support of the people in Gaza. And it is manifested in 2019 through Tal’at, the groundbreaking women’s movement fighting against patriarchaland colonial violence.

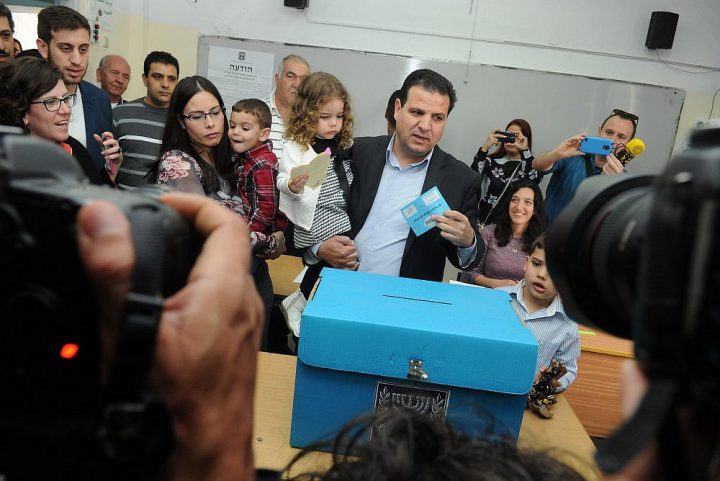

Political elites are also reorganizing. After years of fragmentation, the Joint List has superseded the High Follow-Up Committee as the national political body that represents the community’s diverse factions under a united, democratically-elected umbrella. The List is now a key political address for local constituents, foreign dignitaries, and even Israeli authorities to engage with the community’s concerns. With its controversial decision in September to recommend Benny Gantz as prime minister, the List has shown its willingness to break political taboos to try to counter the status quo. And it has demonstrated to the world that there is only one truly democratic, anti-occupation camp in Israel, and it is led by Palestinians.

These two streams of leadership, which are frequently at loggerheads, suffer numerous problems and obstacles. Socio-political differences between Palestinian communities in the north, center, and south fragment their collective mobilization. Ideological battles and personality clashes within the Joint List mire its strategic impact. Gun violence has dominated the community’s concerns, exacerbated by historic distrust of the police and social impunity enjoyed by perpetrators. The splintering of the Palestinian national movement has muddled the community’s political direction. The one-state reality poses new questions for the struggle against a solidifying regime of apartheid.

In spite of these challenges, Palestinian citizens are establishing themselves as central figures in the struggle against Israel’s worsening policies. And while this movement is crucial, it should not mislead anyone into believing that the community’s troubles are solely with the right. The groundwork for the Jewish Nation-State Law, like all other Israeli laws and policies before it, were laid by the Zionist left long before Netanyahu came to power. Palestinians in Israel may be better off than previous generations, but they know as well as their predecessors that it does not matter if they have blue IDs, speak Hebrew, economically integrate, or vote in elections: in a “Jewish state,” they will always be second-class citizens. They did not need another racist law to learn that — but at least it has made the justice of their cause much clearer.