Ten days before Donald Trump will be inaugurated in Washington DC on January 20, there will be another inauguration in Caracas. Two contenders claim they will receive the Venezuelan presidential sash.

By Roger D. Harris

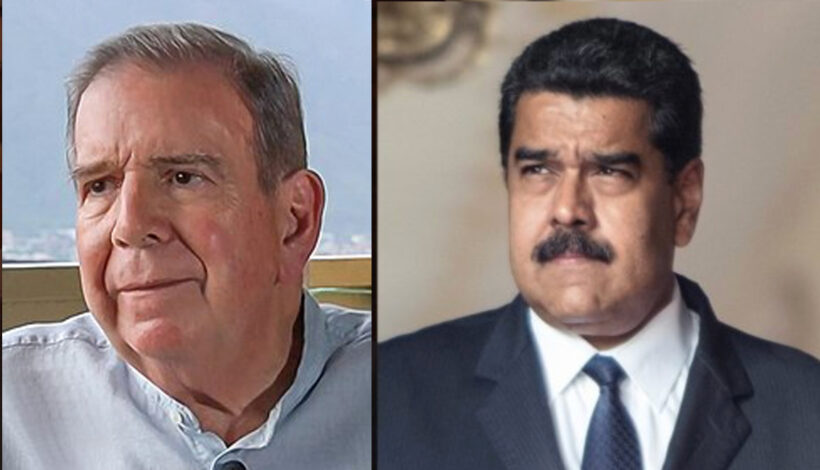

Nicolás Maduro’s claim to the presidency is backed by the finding of the Venezuelan electoral authority (CNE) that he won 51.95% of the vote in the July 28th contest. This was subsequently confirmed by their supreme court (TSJ), after a thorough examination of the voting records.

Edmundo González Urrutia’s claim is based on informally collected voting tallies from 70 to 80% of the precincts showing that he won anywhere from 55 to 75% of the total vote (depending on the source). In contrast, the official CNE electoral authority found he lost with 43.18% of the vote.

González was summoned by the Venezuelan courts to show whatever evidence he had of his supposed victory, which he refused to do. In fact, he took no legal action of any kind to prove his contention, leaving the Venezuelan government no constitutional means of accepting his presidential claim even if it were valid.

But González has a big stick to back his presidential pretentions. As Washington’s designated president-elect of Venezuela, he need not respect the institutions of his home country. In fact, he considers them all– constitution, courts, electoral authority, legislature, and executive – illegitimate.

Extraordinary threat excuse

The US has sought to overthrow Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution for nearly its entire quarter-century of existence. In 2002, a short-lived US-backed coup temporarily deposed President Hugo Chávez, who was reinstated by a popular uprising.

Since then, the US has conducted a hybrid war against the Venezuelan people. Washington has tried to make conditions so unbearable that Venezuelans would turn against their own democratically elected government.

US President Obama declared “a national emergency,” alleging Venezuela posed an “unusual and extraordinary threat.” This was his cynical excuse to impose unilateral coercive economic measures in the form of illegal collective punishment, euphemistically called “sanctions.” Each subsequent US president has continued and even intensified the sanctions, almost crashing the Venezuelan economy around 2019-2020.

Despite the unrelenting US siege, the economy has been recuperating with one of the fastest growing GNPs in the hemisphere. While reversing the economic tailspin, under Maduro’s leadership, the recovery has been partial. The popular sectors still disproportionately suffer from the sanctions, which was Washington’s intention. This leaves a substantial segment of the population, especially the youth, with chronically deteriorated living conditions, despite allocation of some 78% of its budget to social purposes.

For now, the far-right does not have popular support. But discontent could be exploited to destabilize the government in the future.

Maduro – Machado – González

After Chávez died of cancer in 2013, his foreign minister and designated successor, Nicolás Maduro, won the presidency in a snap election and was reelected in 2018. Neither election was recognized by the US, basically because Washington’s policy was not engagement but regime change. So it came as no surprise when the US announced before the 2024 election took place that, if Maduro were declared the winner, Washington would consider the contest illegitimate regardless of the vote count.

After the polls closed on July 28, the Carter Center, a partly US-funded NGO, rushed to announce that the election was undemocratic. Then, before the results could be verified, the US State Department declared that Maduro had lost. However, it took nearly four months, until November 19, for the US to anoint González as the president-elect.

Meanwhile, the European Union (EU) declared González to be the president-elect on September 19. They went even further to proclaim far-right Venezuelan politician María Cornia Machado as the leader of the opposition. Although Machado is arguably the best known opposition figure, the distinction as “leader” would be questioned in Venezuela where she is roundly resented by her confederates.

The US, joined in this case by its junior partner the EU, has consistently intervened within the Venezuelan opposition by sidelining the more moderate nationalist elements, who democratically compete in elections, in favor of the far-right insurrectionist fringe.

Speaking of which, Machado had been pardoned for her involvement in the 2002 US-backed coup. But she was subsequently barred from running for office in 2015 for constitutionally-determined treasonous activities. Her electoral disqualification was judicially reaffirmed prior to the 2024 election. But that did not deter the US from identifying her as the next Venezuelan president.

After being selected by Washington, Machado staged a bogus “opposition primary” administered, not by the electoral authority, but as a private affair run by her US-funded NGO. Predictably, she won by an incredulous landslide, which was contested by her fellow opposition politicians.

Because she was barred from being on the ballot, Machado ultimately had to settle with personally choosing a surrogate, Edmundo González, to run for president. The former diplomat, had no governing experience and was completely unknown. But that didn’t matter to the US backers, because they were not interested in winning but in discrediting the Venezuelan electoral process. Their unpopular radical-right agenda – wholesale privatization, austerity, and foreign policy realignment to favor US/Israel – could not be achieved by a democratic vote in any case.

US post-election offensive against Venezuela

Since the election, an intense media offensive included the misuse of statistics to erroneously question the official voting results. Meanwhile, an obsession with the minutia of Venezuelan electoral procedures and “irregularities” has been designed to create an aura of distrust, obscuring the far greater offense of US intervention in the internal affairs of Venezuela.

Within ten days of each other, both the US House of Representatives and Venezuela’s National Assembly passed bills bearing the name of Simón Bolívar, the 19th century revolutionary leader who played a pivotal role in securing independence from Spanish rule.

This was anything but an indication of reproachment between the two countries. Nor were the Yankees honoring the “Liberator.” The eponymous US legislation was akin to, say, the Zionists systematizing their genocide in a bill named for Nelson Mandela, after South Africa charged Israel before the International Court of Justice.

The “Banning Operations and Leases with the Illegitimate Venezuelan Authoritarian Regime” (BOLIVAR) Act passed the House on November 18 with strong bipartisan support. Trump’s pick for national security advisor, Michael Waltz, and former Democratic National Committee chair, Debbie Wasserman Schultz, cosponsored the legislation.

The BOLIVAR Act would codify into law existing regime-change measures imposed by Washington to overthrow the Venezuelan government, but does not include new measures. It has been referred to the US Senate.

This was followed on November 27 by new US sanctions on 21 Venezuelan officials for supporting President Maduro’s “efforts to fraudulently declare himself the winner of Venezuela’s July 28 presidential election.”

In response to the US legislation, Venezuela passed the “Liberator Simón Bolívar against the Imperialist Blockade” Organic Law on November 28. Its purpose is to “protect sovereignty” against economic aggression. Penalties are mandated for endorsing sanctions, recognizing parallel state powers, promoting violent plots, or collaboration in confiscating Venezuelan assets abroad. A Hinterlaces poll from October shows 63% support for prosecuting politicians who solicit foreign sanctions on their own citizens.

Upcoming showdown at the inauguration

After the election, González voluntarily left Venezuela for Spain in a transfer negotiated with the Caracas and Madrid governments. He then went on a European “victory tour” where his reception was underwhelming.

Meanwhile, Machado called for “great protests” in support of González’s presidency on August 17 and again on December 1 in Venezuela and abroad. These fizzled pathetically even by the opposition’s own admission. Time and again, the far-right opposition has shown that it does not have strong support on the ground. But, with Washington covering their back, do they need it?

The US blessing of González as president-elect has emboldened the far-right opposition. González predicted, “I’m convinced I will somehow travel to Venezuela to take over.”

Stumbling through a script, González made cryptic threats, alluding to the Maduro administration as a “de facto government… [that will] end up leaving power through relatively unexpected situations. We require the maximum support from the world’s democracies.”

This has ignited a flurry of media commentary about “military assistance from the international community.” In other words, US intervention; what the Americas Quarterly perversely calls “actions to restore democracy.”

President Maduro, commenting on US Southcom activity with neighboring Guyana, warns about a possible “preparation of an attack.” The US response is “everything is on the table.”

Machado had previously rejected any negotiation with the “illegitimate regime” over the “transfer of power” to her and her surrogate González. But most recently, Machado has signaled that she was open to negotiating with Maduro about how he would leave office.

This would be analogous to the Green Party’s Jill Stein conceding that she would be willing to talk to Donald Trump about her replacing him as US president. The comparison ends there, because Stein does not have the backing of a superpower. And that raises the specter of what Washington’s ultimatum to Maduro to step down or less has in store for Venezuela.

Déjà vu all over again

For now, two contending forces claim the Venezuelan presidency, harking back to 2019.

Then the US recognized the self-appointment of Juan Guaidó as “interim president.” At the time, the US security asset was unknown by some 80% of Venezuelans and had never run for national office. Over fifty US allies ended up recognizing him, and he was used as an excuse to illegally seize billions of dollars’ worth of Venezuelan assets held abroad. Ultimately, the Venezuelan opposition itself disowned the corrupt Guaidó in December 2023.

Once again, the US with a growing number of allies have in the form of the Machado-González team a new puppet president for Venezuela.

Venezuelan Foreign Minister Yván Gil quipped: “‘The only place you can’t come back from is from being ridiculous,’ so goes the popular saying. However, Blinken, a self-confessed enemy of Venezuela, insists on doing it again.”

Roger D. Harris is with the human rights organization Task Force on the Americas, founded in 1985, and the Venezuela Solidarity Network.