Combatants for Peace is a binational grassroots movement that was founded by former Palestinian and Israeli combatants in 2006. Its goal is to end violence and occupation and to promote a peaceful and just solution to the conflict. The movement is based on principles of nonviolence and emphasizes dialogue, education and collective action to build bridges between the societies. It is proof that working together is possible even in a deeply divided environment, and offers hope for a better future.

Rana Salman, co-director of Combatants for Peace, took the time for a conversation with Pressenza while visiting Berlin for a conference. The interview was conducted by Reto Thumiger German editorial department and Vasco Esteves from the Portuguese editorial department.

Reto Thumiger: Combatants for Peace is a grassroots movement founded by former Israeli and Palestinian fighters. At events, the organization is always represented by two members, one Israeli and one Palestinian, which I think is an exciting approach. It stood out to me that the steering committee is co-led by two women, which I wouldn’t necessarily have expected.

Rana Salman: I joined the movement four years ago. Back then, very few women were involved, the group was heavily male-dominated. The change came slowly, perhaps not intentionally. But the activists, the leading circle and our co-founders were open to making more space for women and including them more.

I have a completely different background from our founders, for example. I was never a combatant and didn’t actively contribute to the cycle of violence. But that doesn’t mean I don’t have a place in a movement that dedicates itself to nonviolence and common humanity. On the contrary, it opens doors when people with different backgrounds are included –– not only former combatants, but also activists for nonviolence, women, young people, and conscientious objectors from Israel. This diversity has strengthened our movement.

When I joined, many things were improvised: A small room in Tel Aviv served as an office, activists met up in person in the West Bank to plan actions. Despite limited resources, the desire to improve things motivated us to continue.

With time, the movement began to grow, and it became clear that it needed more structure –– not only as a movement, but also in an organizational sense. What we were doing was incredibly important, and more and more people believed in our work and wanted to support us. That was the moment when it became necessary to grow, to professionalize ourselves and to bring in qualified staff. Only then could we develop programs, reach a wider audience and in particular include more young people from both communities.

I joined during exactly this period. We began to build an office in Beit Jala –– essentially, we started from scratch and began to create a structure that was suitable for the scale and importance of our work.

Vasco Esteves: And when did the movement begin? Has Combatants for Peace grown noticeably since the start of the war in Gaza?

The movement was founded in 2006. We grew especially after the start of the war –– more people joined our movement. One example of that is our work in the Jordan Valley, where we provide a protective presence for shepherds. Our activists, along with a coalition of organizations as well as individuals, accompany shepherds to protect them from attacks. We noticed in doing so that an increasing number of Israelis were interested in joining us, learning and participating.

“Hope isn’t an abstract idea. It’s an action.”

On the Palestinian side, however, it was a challenge for a long time to get young people into the movement. We launched an educational program for Palestinian youth between the ages of 18 and 28 –– a 6-month program that accepts 15-20 participants per cohort. When we began it three years ago, it was extremely difficult to find enough young people. There’s still a lot of resistance to joint initiatives and cooperation with Israelis in Palestinian society. Many people are mistrustful or feel uncomfortable in shared spaces.

After October 7th, we had to suspend the program for a few months for security reasons –– due to road closures, restriction of movement, and the danger of settler violence. Our participants come from various parts of the West Bank, and we didn’t want to expose them to any unnecessary violence, especially the young men, who are often targets of military violence.

When we started advertising in March for the next cohort, we were blown away by the interest: 93 young Palestinians from throughout the West Bank had applied. That was a hopeful sign. This time, it wasn’t us who were looking for them –– they had found us. They’re curious, want to get to know the other side, share their stories and speak their truths. Maybe they see this space as a platform to come together, to express themselves and discover new paths.

But it remains dangerous. Since the start of the war, it’s even difficult for us to express ourselves on social media. It can be very dangerous just to like a post. Palestinian citizens in Israel have been silenced for years. They don’t share or like anything on social media anymore, because they could be arrested. We know of several cases where young people were detained at checkpoints. Their cellphones were searched, and if they had pictures of Gaza or critical conversations on them, they would be arrested or even beaten. It’s a big risk.

“Without inclusion, peace processes will fail.”

RT: I initially asked this question [about women leaders – Translator’s note], because women have played a central role in many peace processes throughout the world. These processes wouldn’t have taken place without women participating in them.

In order for peace processes to be truly effective and long-lasting, they have to include different voices and needs. Such processes often fail, because they continue to exclude marginalized groups in society –– women, young people, all those who normally don’t have a place at the negotiating table. That’s one of the main reasons why many peace initiatives aren’t successful. That’s why we’re always talking about inclusion. Everyone has to be part of the process.

Research and experience from previous conflicts show clearly how important the role of women is. They have frequently mediated ceasefire agreements, participated in negotiations and contributed to reconciliation. Women make up a large part of society on both sides of the conflict, and they’re the ones raising the next generation. They don’t just play an important role –– they are essential. You can’t just ignore them or remove them from the equation.

What we’re also seeing is that many peace processes overlook humanizing aspects which women frequently contribute. They’re rarely about empathy or reconciliation –– instead, the negotiations often stay at a purely technical level: explanations, signatures, formal agreements. But women bring in another kind of depth. As sisters, daughters, mothers –– they’re concerned, they sympathize. They can relate to the pain, the grief and the sorrow of the women on the other side. This ability to identify with other people is invaluable to every peace process.

Even if a peace process leads to a treaty or a ceasefire, there is still the task of creating trust, building bridges, and fostering reconciliation. Those are exactly the areas in which women and society at large play a critical role. There would barely be grounds for peace without this work.

VE: What central topics and activities does Combatants for Peace emphasize? What are the most important areas that the movement is active in?

Our main focus is on-the-ground work, since we’re a grassroots movement. That means that we’re always present –– whether at protests, demonstrations, nonviolent actions or solidarity initiatives. I’ve already mentioned one example, accompanying the shepherds in the West Bank to protect them from settler and military violence. In the past two months, we’ve supported families during the olive harvest by accompanying them to their land so that they could safely pick olives.

Along with these actions, we also organize educational programs. As I already mentioned, these programs are designed for young Palestinians and Israelis who learn about nonviolent resistance, nonviolent communication, and other topics that are often missing in typical education. We call that „alternative education“ – it’s about learning from others and telling your own story. This is a powerful tool for us to build bridges. That’s also how our movement began: with meetings where people shared their stories and learned, for example, how to use social media to spread their messages.

Another focus area is awareness-building work with young Israelis before they join the army. Many of them have never met a Palestinian before and grow up with stereotypes –– the other is the enemy, end of discussion. We try to break through these barriers by organizing meetings that open them to new perspectives. Fortunately, we’re seeing a growing trend in Israel: More and more young people are refusing to do military service. Just recently, 130 reservist soldiers openly announced their refusal to serve –– they even signed an open letter. That’s new, because military service used to be seen as an honor; people felt they were defending their country. But now more and more people recognize that the army isn’t defending anything, but rather committing war crimes. They see the occupation and its effects first-hand.

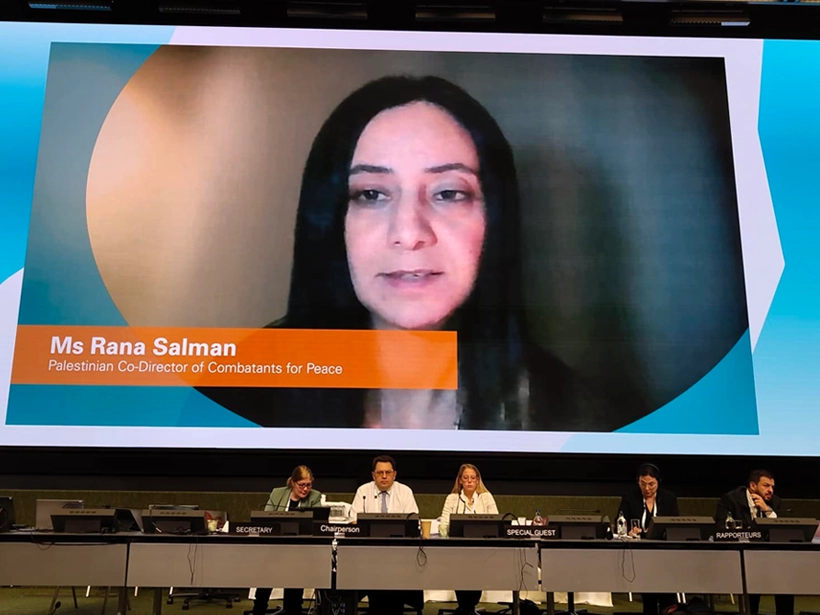

Rana Salman, co-director of Combatants for Peace (photo credit: Vasco Esteves, Pressenza)

We also organize sight-seeing tours in Palestine and Israel for Israeli groups and diplomatic missions to show how the occupation affects people’s lives and how settler violence puts a burden on shepherds and communities. In the process, we document human rights abuses and increase awareness about them.

Another important aspect of our work are annual ceremonies such as the collective Israeli-Palestinian remembrance day. This is a holy day in Israel to commemorate fallen soldiers. We do it differently: We commemorate all victims of the conflict –– Israelis as well as Palestinians. That’s controversial, of course, because we’re changing the narrative. Instead of emphasizing the victim role or hero-worshipping, we try to humanize the other side.

RT: The goal is to commemorate all victims of this conflict?

We don’t invite any politicians or government representatives to our memorial ceremonies. The grieving families speak instead –– the people who have lost loved ones due to this conflict. Another important ceremony is the collective Nakba Remembrance Ceremony, which we hold every year on May 15th. We commemorate the Nakba, the Palestinian catastrophe of 1948, and engage with the facts of what happened back then.

“The occupation doesn’t provide safety or protection –– for anyone.”

In Palestinian society, May 15th is a day of mourning –– a day of remembrance for the displacement, loss, and occupation. In Israeli society, on the other hand, the topic of the Nakba is taboo, because the day is linked with the founding of the State of Israel and its independence. For this reason, our shared remembrance ceremony is an important step, because it’s important to acknowledge the past in order to create a better future.

During this ceremony, we hear stories from Palestinians and Israelis, from refugees who lived through the events of 1948. Many of them live in refugee camps today. We bear in mind that these first-hand accounts will become rarer in the future as the eyewitnesses from those times get older. The soldiers who served in 1948 and witnessed the events will also not be available to us for much longer. It is therefore all the more important to document and share these stories now, so that each side can get to know the stories of the other.

VE: So your work comprises not only reactive measures, but also proactive initiatives?

Exactly, it’s a type of re-humanizing effort. Especially now, after the events in October, there’s deep mistrust and dehumanization of the other on the Israeli side. Many think of Gaza only as „Hamas“ or the enemy, without empathy for the children or the suffering of the people there. This distance arises out of the pain and the trauma that both sides live with.

Both sides focus on their own pain: The Israelis, because they live with loss and fear, since there are still hostages in Gaza; the Palestinians, because they are confronted with destruction, displacement, and a humanitarian catastrophe. This isolation makes it difficult to see the other side. But that’s exactly where we come in –– with the goal of building bridges, promoting empathy, and reestablishing humanity on both sides.

“Why should what happened in Europe not also be possible for us?”

RT: In Germany, there is often a tension between the historical sense of responsibility toward Israel and the commitment to international human rights. How should Germany deal with this contradiction, in your opinion? And what role could Germany play in building bridges and actively contributing to the promotion of peace in your region?

I know that the conflict between Israel and Palestine is a very sensitive topic in Germany –– due to the history, the past, and perhaps feelings of guilt as well. It’s not easy to change one’s convictions, especially in terms of the government’s politics. There seems to be almost unconditional support for Israel in Germany, which is justified by the right to self-defense and the protection of Israel’s existence. That’s of course legitimate, but it doesn’t mean that this support should be unconditional. There are limits, especially given international human rights abuses –– and I think the limit was crossed a while ago.

For that reason, I see a kind of divide in Germany: Many people want to support Israel, but feel obligated to human rights. That leads to a contradiction. Germany is at a point where it must decide how to position itself. I hope that it will decide for international human rights.

When I look at Germany from a distance, I see Pro-Palestine protests, Pro-Israel protests –– both of which are narratives that don’t really bring us further in the region. They force people to choose a side rather than to build bridges. That often leads to dehumanization of the other side. For example, when people post that they’re on the side of Israel or Palestine, or when they use slogans that could be offensive for the other side. It becomes a competition about who’s right. But in a time like this, in the middle of a war, that doesn’t bring us further.

What we really need is support for solutions and for peace. Arms shipments, including from Germany, only prolong the war and feed the war machine. There should be more resources put into peace efforts and negotiations instead, in strengthening the members of society who do peace-building work. That could change the narrative and the dynamics of the conflict. As long as Germany and other countries provide arms and resources, war will remain an option –– that’s the reality.

“Germany has the opportunity to take on a more proactive role for peace.”

RT: Many people in Germany feel strongly bound to the commitment that no war should ever start on German soil again. For many people, that includes not only military operations, but also arms shipments and every form of logistical support for wars. Given the current global developments, many people who are dedicated to peace feel frustrated and powerless. What would you say to these people?

To the people in Germany who are frustrated, I would like to say: Don’t lose hope. We haven’t given up hope in a solution in our region, because we know that it’s possible. It’s not our destiny to live in conflict forever. Europe has shown that transformation is possible. Who would have thought a few decades ago that countries like France and Germany, once bitter enemies, would work together in close partnership and friendship today? Why shouldn’t that also be possible in our region?

There’s a chance. But we need international actors like Germany, who can take a more proactive role. Sometimes we feel that we can’t succeed alone because international powers influence the conflict so heavily. Maybe Germany often holds back because the USA is Israel’s most important ally. But that’s precisely why Europe, and in particular Germany, has the opportunity to adopt a different stance and provide a counterweight.

RT: What is the source of your strength, your belief and your motivation? What inspires you every day to do what you do and keep fighting?

I can’t share the details, but one reason that I’m here in Berlin is that I work with a group of Palestinians and Israelis to change reality, create new possibilities and advocate for our shared vision of a better future. These kinds of meetings like the one we’re having here, with proponents of peace from both sides, always give me hope. And at home, with Combatants for Peace, I gain strength from our work: When we meet, plan our next actions, discuss, sometimes disagree, but still persist –– that feels like a binational community.

In such moments, you can see that our vision is possible. It’s not a dream, not an illusion. It’s happening right now, in front of our eyes.

RT: If it’s possible on this level, why couldn’t it also be possible on the societal level?

Exactly. We come from different backgrounds, convictions, and perspectives, and yet we work together, dream together, fight together –– in nonviolent fashion, of course. We’re fighting against a system that doesn’t serve Palestinians or Israelis. The occupation doesn’t provide safety or protection for anyone, we know that. And from the experience of our founders, whose lives were previously entangled in violence, we’ve learned that violence only leads us to remain stuck in the same cycle.

That’s why we have to break out of this cycle. We know that there is only a political solution to our conflict. And we have to work together to create a better future for all. Hope is not an abstract idea to me. It’s an action, something that we have to work for –– a clear path to make change.

Thank you so much for the interesting and hope-inspiring conversation. We wish you all continued success in your important mission!

Translation from German by Olivia Howe