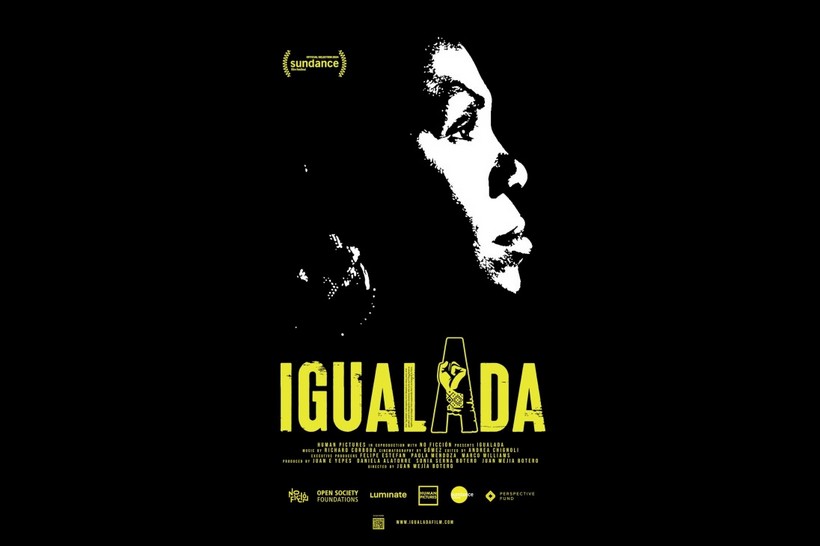

IGUALADA: An “igualada”, a derogatory term (based on class, race, and gender) used to designate someone who acts as if they deserve rights and privileges that supposedly don’t correspond to them.

Pressenza presents an interview with Juan Mejía Botero, director of the film Igualada, which portrays Francia Márquez’s trajectory of the struggle for the environment and the territory. The film is a trajectory of her struggles, not only the campaign for the presidency, but it also traces the trajectory of this social movement, a movement led by young people, by young women above all, by diverse LGBTQ+ communities, and by ethnic peoples.

Who is Juan Mejía Botero?

I was born in Colombia, but since I was 17, I have lived alternating between my country of origin and other places in the world. For the last 11 years, I have been living in New York. It is the longest stretch of my life that I have lived outside of Colombia. I am married and have two children.

I studied anthropology, then I did a master’s degree in Latin American studies, specifically in Latin American politics, and later I studied film.

Since I started, I have been doing a lot of work on the subject of forced displacement in Colombia, especially in the Colombian Pacific, so I have a series of short films and feature films about displacement. The first one was in 2009 and it was called “Desterrados” (Banished), then I produced “La Toma” [Translator’s note: La Toma is an Afro-Colombian community], which was after meeting Francia Márquez, then in 2010 we made “Independencia ¿para quién?” (Independence, for whom?) starring Francia Márquez, with three other characters; and then I made a feature film called “La lucha por la tierra” (The Struggle for Land) which deals with displacement in the Pacific and the oil palm.

In 2016, I made “Muerte por mil cortes” (Death by a Thousand Cuts), a documentary filmed on the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic that has to do with the destruction of forests in the Dominican Republic and the trafficking of coal between the Dominican Republic and Haiti, but obviously it is an issue of social justice, inequality and racial justice. Since then I have done many things here in the United States around racial justice and the prison system. In 2020, Francia Márquez called me and told me that she was running for president of Colombia, so we revisited Francia’s life story and made the film Igualada.

Could you tell us what motivated you to make the film Igualada about Francia Márquez?

Well, I was very impressed with Francia from a very early age. In 2005, I was working with the Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN), through a very nice campaign called “Las caras bonitas de mi gente” (The beautiful faces of my people). It was the first time that the census included the category “Afro-Colombian” and it was thanks to that moment that I met Francia Márquez.

In 2008, I traveled with her to the United States. I was presenting one of the documentaries about forced displacement and she was talking about the moment that her community was experiencing in the town of La Toma and how they were fighting to remain in their territory.

I was already very impressed by Francia, especially by the conviction shown by someone so young – in 2006 she would have been 17 or 18 years old – and already willing to risk everything (in Colombia, clearly risking everything is risking your life) for her community and for her territory. The fact that someone so young was willing to risk everything left a huge impact on me.

From that moment on, she told me that she wanted to do something to document and show what was happening in La Toma. In 2009, the opportunity arose and with a Colombian-American director, Paola Mendoza, we produced this short film together called “La Toma.” At that time, Francia was one of the leaders, she was leading that fight, so she stars in this film.

In 2011, we made “Independencia ¿para quién?” (Independence, for whom?) where she is also one of the protagonists. So I already had that experience with her, a long road. When she called me in 2020 and told me that she was running for president of Colombia, it was very natural for me to continue documenting. As far as Francia goes, this is going to be historic and it must be documented.

At first, she wasn’t so sure, I had to convince her a little and in the end, she said – I remember very well – “no films are made about communities like mine, or women like me, so ‘go for it’”. That’s where we started, since 2020, with a wonderful team, a very community-based task.

And from 2020 until she became vice president… what a thing… how lucky I was to have started with her and that she has been able to reach the vice presidency of the Republic. It’s incredible, it is a great fortune, you cannot imagine that, one cannot expect that, and if one expects it, it does not happen…

Photo credits: Darwin Torres. humanpictures.me

Could you give us a brief synopsis of the film Igualada?

Igualada portrays Francia Márquez’s history of struggle for the environment and for the territory; it is a history of her struggles, not only the campaign for the presidency, it also traces the history of that social movement, a movement led by young people, by young women above all, by diverse LGBTQ+ communities, and by ethnic peoples.

Igualada is a portrait of hope, in reality, of a very historic moment that I believe marks a ‘before” and an “after” for Colombia, and who knows if it will be repeated in our country.

But it is a portrait of hope in a country as battered and as alienated from traditional politics as Colombia; with Francia, there is the opportunity to believe again that another type of politics is possible. So it is a very nice moment, since in Colombia, over time, it will acquire more and more value, as a historical document.

Who is Francia Márquez in private, away from that public sphere?

As I told you, Francia Márquez is a woman with an unwavering conviction regarding justice, a woman with a very good sense of humor who is an artist inside, she loves to sing, she loves to compose, to act, but she is a person who has had a very hard life. Being threatened with death since one was 18 is a very, very heavy weight to carry and she is a woman who has received many blows and a lot of hate. I think that perhaps that has hardened her, but well, who wouldn’t?

Photo credits: Darwin Torres. humanpictures.me

She once told me that she is like a steel bar that is put in the fire and hit with a hammer, then it cools down and ends up hardening. But when I hear people say that she is full of hate, that she is resentful, I don’t think it is the case.

Francisco Márquez has no hate or resentment. She does have anger, but for me it would be strange to live in a country like Colombia all your life and not be angry; we are one of the most unequal and violent countries in the world, so it is natural for a woman like Francia Márquez, who has spent her whole life fighting for the environment, racial justice and equality, to be angry; moreover, I think that also motivates her. But inside she carries strength and courage, she is also a woman with a very good sense of humour, a woman of convictions, with a strong and critical character. We should all be angry. Yes, I think so, because I think that growing up in Colombia and not being angry is like being very disconnected from reality.

Let’s go to the film. What were the most difficult moments of that recording? Because I imagine that being behind activists in Colombia, as you say, is difficult, and there must have been many of them. Surely there were many complex moments.

I want to say first of all that it was a collective work, I don’t remember who said that beautiful saying “The struggle is a collective poem” (1), and so was this film.

We have a team of women based entirely in Colombia: Sonia Serna Botero, our producer, Gómez, our director of photography, and Eliana Carrillo, our field producer; and from New York we have Juan Yepes, who is my great producer, with whom I always work. Juancho and I travel constantly to Colombia, but there in the daily struggle were Sonia, Gómez, and Eliana.

At the beginning of the film it was very difficult because we had very few resources and Francia’s campaign for president had even less. So a lot of that initial work was done by them with Francia; there was no security plan yet, because there were no resources for the campaign, so they crossed the entire Colombian Caribbean region and part of the Pacific region in those conditions.

While Francia was beginning to become known, Juan Yepes and I traveled and relieved them; sometimes we all travelled together, and other times we split up, but all of that was very difficult, the beginnings were very difficult. Also, because it was in the middle of a social outbreak and in the middle of a pandemic.

So we were dealing with the pandemic, dealing with the social unrest in Colombia and trying to follow Francia between the lockdown and then the social unrest. Francia went out to the marches, she accompanied the strike very closely, so we also accompanied her very closely, following her, and that was very hard. The other thing was the campaign for president itself, a campaign of very committed young people, with very little political experience, with very few resources.

The film, I think it was finished three times… three times we said ‘this is as far as the campaign went’, there was simply no more money or simply the necessary signatures were not obtained, then the film was finished, and we had to think how to close it, without it being hopeless because we always felt that it was a hopeful process in any case.

And suddenly the endorsement of AICO (Movement of Indigenous Authorities of Colombia) arrived, so the film started again, and then the endorsement of AICO fell, so the film was finished again. Then came the endorsement of the Polo (Polo Democrático political party) and then we started filming again and well, we continued until the end of the road, but there were many hard moments.

The financing of the film, then, was found little by little, as we progressed, there was no long-term visibility, and we had to react almost daily. We started with a grant from the Sundance Institute and that gave us enough for the first shooting trips, but little by little we had to raise more money, the film was financed with this grant and with other grants from foundations in the United States: the Luminate, Open Society and Perspective foundations, those were the funders. But of course, the money came from some of the funders and when the money was running out, more came in for the next part of the film, and so it went on until the end… there was a lot of difficulty to go to the end…

Speaking of difficult moments, you see in the film a moment in which Francia is in a public event of her campaign, and suddenly the security people begin to protect her and remove her from the stage because there is a laser pointed directly at her. What can you tell us about this situation?

Of course, it was a moment of fear and confusion because no one knew what was happening. Finally, it was discovered that it was a laser that was directed by a young man from a nearby building. It is something that can be frightening and can generate panic, but in reality, it did not turn out to be anything serious. I feel that the hardest moments were the longer ones because as Francia’s campaign gained momentum, the acts of hatred intensified.

Especially those of a racist, elitist, misogynist nature. In the beginning, there was also a little bit of condescension, and people said: “Oh, look at the pretty little black girl struggling to better herself”, that kind of paternalistic racism. But when suddenly Francia had a chance to come to power, everything turned into pure hatred, insults, and attacks. Francia Márquez is strong and manages to absorb most of these, but sometimes all this ends up affecting and discouraging. However, in general, she manages to remain very firm, and of course, if she remains firm, one feels that she also has to continue.

There is another moment in the film where you see Francia somewhat emotionally affected because the work of the campaign is not generating the signatures needed to boost her candidacy. Francia picks up her cell phone and starts receiving a lot of hate messages, which you decide to show simultaneously on the screen. On France’s face, you can see a lot of disappointment, but at the same time, a great determination. Where do you think she gets her strength from?

I don’t know, but I feel it’s a struggle she’s been fighting since she was a teenager. There is even a very nice interview from Francia, I don’t remember now who did it, where she is shown very young fighting to prevent the transnational Unión Fenosa from diverting the Río Ovejas to increase the reservoir of the Salvajina dam, thus eliminating the life options of thousands of indigenous and Afro-descendants of the region. From that time on, she already felt a great inner strength and a great understanding of what the struggle and the problems of her region and her country meant.

So I believe that Francia has often felt like giving up, but I also feel that she has a conviction and endurance that can only be generated with a long history of struggle, and above all an understanding of what that means. In addition, Francia is a supremely intelligent woman who understands the Colombian environment very well. I think that also helps.

When one studies the lives of some people who have marked the history of the world, I think of Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and other people who have produced strong social action, it is observed that they have also been nourished by a deep spiritual life; I do not know if you can say something about Francia Márquez….

Francia is a very spiritual woman and I know that this issue is very important to her. She recharges herself energetically through that spirituality.

Have you talked to Francia about the experience of those first two years in power?

A few months ago, we organized a private premiere of the film for her family and the “Soy porque somos“ [I Am Because We Are] campaign team.

On that occasion, France said something very strong: “We have the State, but that doesn’t mean we have the power”. I was quite impressed by that, and I think it makes a lot of sense. Colombia has been one of the only Latin American countries that has never had a progressive, left-wing government. The same people have remained in power. It’s always been the same families that have ruled in the history of our country – so even if the state changes, it’s not so easy to change the power structures.

Images from the film Igualada. Women, Peasants, Indigenous, Youth.

These power structures in Colombia have been cemented for centuries and I feel, this is my personal vision, that to expect to change these institutions in 4 years is very complicated. There are centuries of the same power. [We are talking about] the owners of the industry, the owners of the mass media, etc. For her and the current government, it has meant hitting against the walls, and I know that this has also been very difficult for Francia because she is aware that there was a lot of hope in her and [then there is] the anguish of not being able to respond as she would like; but it is a very complicated mission.

When we presented the film, people told us that it was very difficult not to let pass what one hears every day on Caracol, RCN or other mainstream media radios, which are constant attacks on the government. The questioning of Francia Márquez, who cannot spend 10 pesos without being questioned. This did not happen with the last vice-president who went on a trip and nobody calculated how much gasoline was spent. So I believe that for the Colombians who believed in this project, it is a challenge not to let themselves be permeated by all these attacks.

This morning on Blu Radio (which belongs to one of the dominant media outlets) this was said I wrote it: “Francia Márquez is the great disappointment of the Petro government, completely invisible, with a lack of leadership that has not allowed her to preside a Ministry of Equality that has done nothing, and a project execution rate of around 1%. Imagine if Gustavo Petro died like Rodolfo Hernández (presidential candidate in 2022) did, who would be our president? All the journalists on the radio panel begin to attack Francia more and more. One wonders, where is the news? That is, are there credible sources of news here in Colombia? How can we avoid being influenced by all the misinformation that reaches us?

Yes, it is very difficult. Regarding the Ministry, people have no idea what it takes to put together a new ministry. When was the last Ministry in Colombia created? I think it was the Ministry of Labour; this process is very complex, and the bureaucracy that comes with a new ministry is a tremendous thing. I remember that they had been in the Ministry of Equality for months and they still didn’t have computers, and nobody talks about this issue of bureaucracy. It’s not that Francia doesn’t want to execute these projects, it’s that these ministries come with a huge bureaucracy to be able to start operating, that takes months and months, it’s very difficult, very difficult.

How has the public’s reaction been since the release of the film Igualada here in Colombia?

So far the reception of the film has been very nice, however, we know that those who went to the first screening were people who already agreed [with the ideas]. In Cali, in Bogotá, in Medellín, and in Manizales the theatres have been very full, cinematheques like the Tertulia in Cali have been full, I think that in all the screenings in Bogotá, we have also had a huge audience. In the end, people are always very, very excited, very excited, there are tears but there is a lot of hope. That was what we were looking for with the film. I think that this moment of great hope reminds us of a lot, and makes us think that by struggling things can be changed. So, it has been very nice, very nice to talk to people after the screenings, it has been very nice, very nice. I would love for people who are not supporters of this government to see the film [Editor’s note: Between 2022 and 2026, Gustavo Petro is the president of Colombia and Francia Márquez the vice president], I think it would still be very, very valuable. For that audience it would be a portrait of our country, it would help them understand our country a little better. It is also a hopeful film, and I think [that it is so] for all Colombians, regardless of their political position. In addition, the film allows getting to know a historical figure in our country in much more depth, regardless of whether one agrees or not with Francia’s political position.

Francia Márquez marks a “before” and an “after” in Colombian politics, not only for all the black little girls and adolescents in our country, who are now growing up with a role model like her in the vice presidency. It is simply the fact of seeing that in a country with the social structure that Colombia has, with the social inequality that Colombia has, with such established structural racism, seeing a black, rural woman, who did not grow up with the elite, who was not educated with the elite, who does not speak like the elite, becomes the vice president of Colombia: that is something almost unimaginable.

So I think it would be very nice if more people went to see the film, people who are not already a sympathetic audience. Here in the United States, in New York, I remember that during one of the first presentations, a man said: “I am a Uribe supporter, but I really liked this film.” I think yes, that the film is very valuable for all audiences.

In Colombia, accessing non-intimate theatres, but rather more commercial theatres, has been very difficult. The big exhibition companies did not want to distribute the film, and they have almost a monopoly on theatres in the country. The reality is that in Colombia, few people go to the movies, and if they do go to the movies, it is generally not to see national films, and if they do see national films, it is generally not documentary films. So we had greater success in more alternative theatres.

«We are not descendants of slaves. We are descendants of free men and women who were enslaved.» Francia Márquez

Of course the film continues to be presented in Bogotá, Cali and Medellín, and more venues are also being sought. We hope that at the end of 2024 we can launch an impact campaign, which seeks to take the film to both the rural periphery and the urban periphery. That is a commitment that we have had since the beginning of the film, to really be able to take the film to the territories and we also want to take it to many universities and schools in the country.

The film has had a very good run on the festival circuit. We have just finished a tour in Europe (Norway, Germany, Spain, Finland, Holland, Sweden), and it has already been shown a lot in the United States, Canada and Asia. In Africa we will be in about 14 countries, on television; and we have already been in festivals in Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Angola and Ghana.

In South America, in Uruguay, Bolivia, Ecuador, Argentina and Chile.

What did Francia Márquez think of the film?

She saw the film at a very difficult time for the government and I think it was very hard for her to remember all that hope, precisely because of what I told you: she feels the weight of trying to fulfill all that hope. She also criticized me for the fact that she didn’t want a film just about her: where were the rest of the leaders, where were the women of Cali, of the district,…

I made the film that we proposed to make, in which the protagonist was Francia, but she is not a woman who likes to be the protagonist very much, even if she is the vice president of Colombia. So that’s what we discussed initially when she saw the film. But I think she has already accepted it and is beginning to appreciate it more and more. I think that Francia Márquez still doesn’t understand what her vice presidency means, [does not see] the magnitude of that achievement. I think that Colombia doesn’t see it, and over the years we’re going to realize more and more the magnitude of what that means, and with that the film is going to have more value for everyone, including for Francia Márquez.

Thank you Juan for this film, it’s something that fills many of us with hope. It doesn’t matter that many people aren’t going to see the film for whatever reason, I think that it’s that notion of openness to what’s happening that can focus us, seeing the daily life of a person who risked everything and who had that call from a very young age, it’s incredible; you can see it in the film from the first images when she was a child but already had everyone listening to her.

Igualada Film Crew and Profile:

A HUMAN PICTURES production in co-production with NO FICTION

Genre: Documentary

Duration: 81 minutes

Language: Spanish

Director: Juan Mejía Botero

Producers: Juan E. Yepes, Daniela Alatorre Benard, Sonia Serna Botero

Executive Producers: Paola Mendoza, Marco Williams, Felipe Estefan, Juan Pablo Ruiz

Field Producer: Eliana Carrillo

Editing: Andrea Chignoli

Sound Design: Aldonza Contreras Castro

Original Music: Richard Córdoba – La Muchacha

Direction of Photography: Gómez

With the participation of Francia Márquez Mina, La Toma Community, Soy porque Somos Movement

(1) Joshi Leban, author of the phrase “The struggle is a collective poem”, is a feminist activist and defender of human rights. She studied public relations but is dedicated to digital communication.

Translation of Evelyn Tischer