In certain respects, the Currier Museum’s Jean Michel Basquiat and Ouattara Watts: A Distant Conversation may be regarded as a modest exhibition, as it features only six works by Basquiat and seven large paintings by Watts. But the power and significance of an exhibition is not simply a function of its size and scope. Even an exhibition consisting of a single painting – such as Caravaggio’s Ecce Homo currently on view at Madrid’s Prado – can be an extraordinary event. The joint exhibition of Basquiat and Watts is likewise such an event, allowing viewers to appreciate their dialogues with the tradition of Western and African art, and with each other.

By Sam Ben-Meir

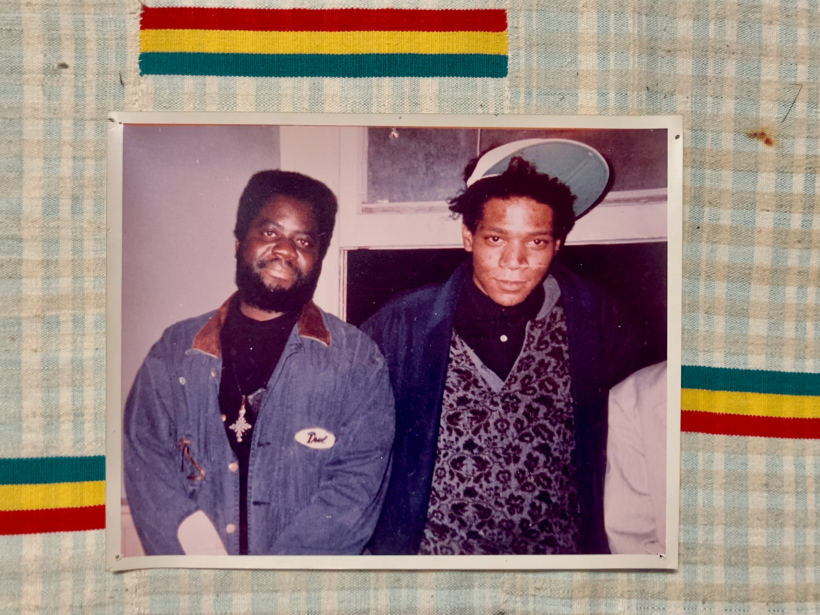

Their deepening friendship was unfortunately cut short in 1988 by Basquiat’s untimely death, a mere seven months after the two artists initially met at Basquiat’s solo exhibition at Yvon Lambert Gallery in Paris that same year. Basquiat had travelled to Africa in 1986, and by a strange coincidence had even visited the village of Korhogo in Côte d’Ivoire where Watts was from. Their camaraderie took root and blossomed from the day they met, with Basquiat insisting upon leaving his own exhibition to visit Watts’ Paris studio. Basquiat was immediately captivated by Watts’ paintings and helped to promote his artistic career. Following their excursions together in Paris and later in New Orleans, Basquiat was planning with Watts to return to Africa when his fatal overdose occurred.

Basquiat and Watts have very different styles, although they both may be seen as neo-expressionists, not afraid of combining figuration and abstraction, employing words, phrases, numbers and other symbols with which to explore certain themes that occupied both painters. A Distant Conversation highlights a common interest in death, truth, and what one might call a certain heroism or courage in the face of our mortality. Consider Watts’ Intercessor #0 (1989), painted only a year after Basquiat’s death. The image is divided vertically: on the right side a white eye or leaf-like shape predominates, sharply defined against a thickly textured, dark brown background; on the left, a silhouette of Ma’at, the ancient Egyptian goddess of truth and justice, identifiable not only by the ankh she holds before her, and inside of which the artist has vertically inscribed his name in yellow – but particularly by the ostrich Feather of Truth atop her head. At the Judgment of the Dead, the heart of the deceased would be placed on a scale and weighed against Ma’at’s feather: this is the moment that decided one’s fate in the afterlife, whether one would continue one’s journey or be devoured by the beast Ammit and thus die a second death.

The painting deals with themes that recur throughout the exhibition. The ‘intercessor,’ referred to in the title, pleading one’s case to God, is not so much the goddess as art itself: for Watts, and arguably for Basquiat as well, painting is an act of intercession, of justifying one’s being – which is also to say, that painting is a kind of magic, it weaves a spell which like all good spells is meant to brace us and fortify us, to aid us in bearing the burden of existence.

Basquiat’s Procession (1986) is about death and intercession as well. Painted on wood, a surface that had long appealed to the artist, the procession consists of four black silhouettes following a larger figure who alone is rendered in color and holds aloft in his right hand a skull that appears to be beckoning, luring or guiding the others onward. There is a certain macabre festiveness to the work, which one might associate with El Dia de los Muertos, for example. The larger figure could also be seen as a kind of intercessor on behalf of the dead – at any rate, he holds not merely a skull but a certain power. He lifts the skull as if it were a kind of beacon or lantern. We are once again confronting the theme of death, but also that of the artist as almost a shaman: Basquiat is not so much depicting a ritual as enacting one. Both Watts and Basquiat are keenly aware of the artist’s role in the traditional African community, in which the artist functions as an integral and organic part of his social milieu. The choice of wood, rather than the more Western and conventional use of canvas, reinforces Basquiat’s interest in distancing himself from what he referred to as the ‘academic’ feel of canvas.

Watts’ Beyond Life (1990) continues with these same themes that bring together and unite the paintings in this exhibition. Again, we find a large, silhouetted figure, flanked in this case by a gravestone. On the right-hand side, Watts has depicted a chapel-like structure – or it may be a larger gravestone – topped by a Coptic cross. As the curators note, we appear to be witnessing a ceremony of some kind, ‘perhaps a rite of passage to the afterlife.’ This interpretation is strengthened by the inclusion of a boat rendered on a small wooden panel attached to the canvas on the left-hand side – invoking, among other things, the ferry that bears the dead to the next world. It is a haunting work, dark in its earthy, indeed soil-like tones that Watts produced from a mixture of dry pigment and sand, creating a thick impasto the gives the work a three-dimensional texture. It is a remarkable example of Watts’ abiding interest in texture and materiality.

Basquiat’s multimedia work, Embittered (1986), consists of two parts, but how they relate to each other and the overall meaning of the work is enigmatic. On the left, we find the word ‘EROICA’ (heroic) repeated numerous times, invoking Beethoven’s mighty 3rd symphony – but in conjunction with plentiful references to boxing: such as ‘GLASS JAW,’ ‘RING,’ ‘EVERLAST,’ ‘RABBIT PUNCH,’ ‘FIXED FIGHT,’ ‘SOFT BELLY,’ ‘KNOCK OUT,’ and others. The repeated words, some of which are characteristically crossed out, encircle the figure of a black man playing an accordion, with the name ‘HOHNER’ beside him, the German company known for manufacturing a wide range of musical instruments. In one sense, the lone musician is standing in a ring. Basquiat was clearly interested in historical black figures – including especially musicians – who are bestowed a kind of royal stature in his oeuvre. Charlie Parker is perhaps the quintessential example of this exalted prominence; but there were others, such as the great jazz and blues singer Dinah Washington, a 1986 portrait of whom is included in the exhibition. Like Charlie Parker, Washington’s life was cut short in 1963, when she died at the age of 39. On the right side of Embittered is the profile of a black figure in the center surrounded by a backdrop of white men and women in various poses, postures and activities. The largest of these is a menacing, ogre-like character, whose left hand is positioned such that it also doubles as a penis, hovering just above the black man’s head. It is hard not to see to this as informing the title of the work, reminding us of the artist’s ‘solitude within the predominantly white art world of the time.’

Basquiat and Watts were very distinctive painters, with differing interests that nonetheless overlapped. Watts’ orientation is more metaphysical: it is the whole of reality and the cosmos that drives his work, and manifests itself in the extensive use of numerology, among a panoply of signs and symbols. Which is not to say that he ignores the political dimension of our human condition, as is evident in paintings such as Corruptions Impunity (2011). However, even there, with its African child soldiers occupying the upper right and left corners, and the human-shaped shooting-range target in the bottom center, Watts includes elements from his rich spiritual visual language, such as floating all-seeing eyes, orbs and significant numbers.

Basquiat’s references are nothing short of encyclopedic, and like Watts he deployed a thick visual lexicon – but his work, while often cryptic, gravitates more towards the historical, socio-political, and ironical. For an exhibition consisting of thirteen works of art, it is an immensely rewarding experience – one that allows us to see Basquiat afresh, and to discover a painter, Ouattara Watts, whose work, while far less well-known, is deservedly sure to gain greater attention.

Sam Ben-Meir is an assistant adjunct professor of philosophy at City University of New York, College of Technology.