By Maxine Lowy

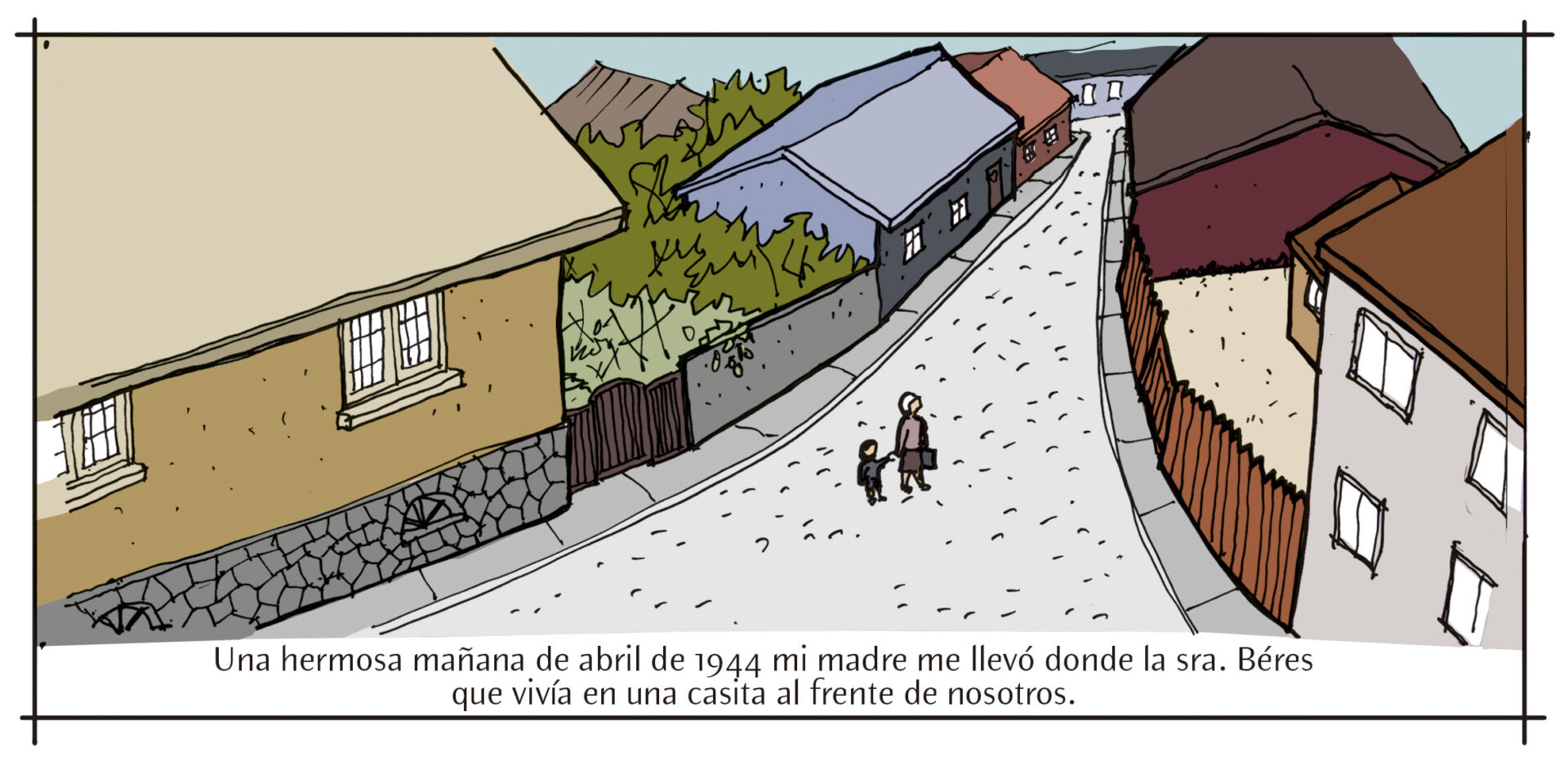

Only six meters separated the two curbs of Dioszegi Street near downtown Miskolc, a city in northeastern Hungary. But in April 1944, one month after the German invasion of that country, it was a nearly insurmountable distance for a 5-year-old boy. It was a gap that entailed the difference between life and death that he would again face decades later in a continent far away.

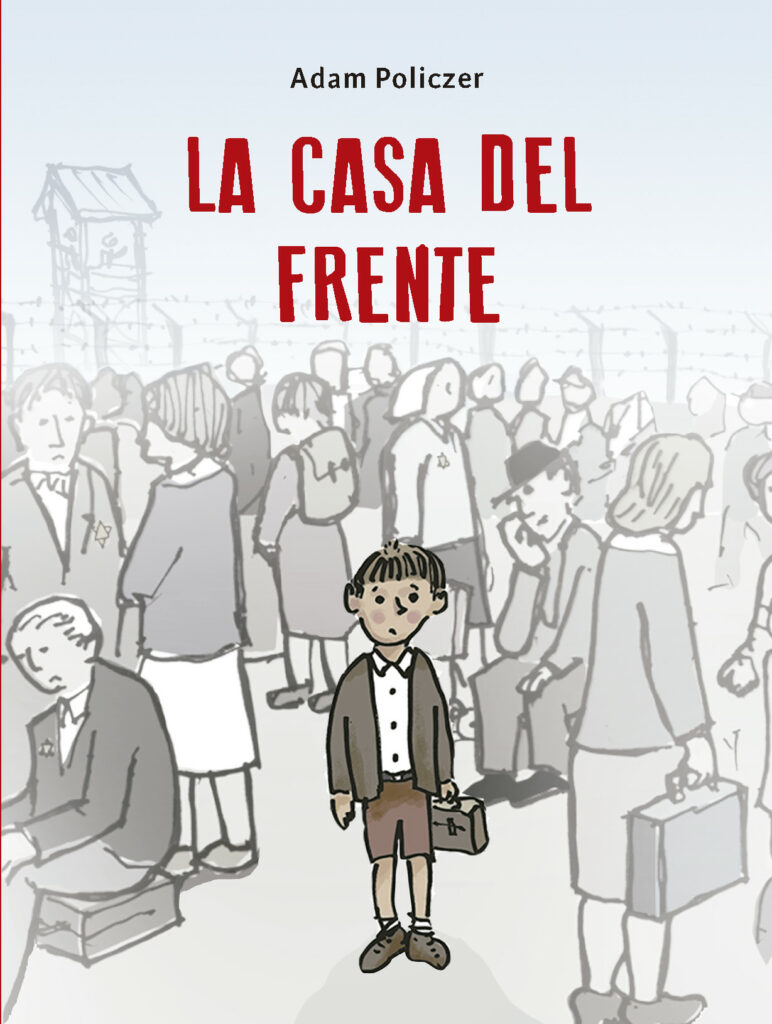

Adam Policzer, the boy from eighty years ago, takes up pencils and paper to illustrate the memory that flows with surprising clarity despite the distance in geography and time. La casa del frente (Lom Ediciones, Santiago, July 2024), his autobiographical comic, contemplates the moral cleavage that can separate a street and a society. In Hungary under Nazi occupation and in Chile under the military dictatorship, he both witnessed and was directly affected by the inconceivable transformation of a peaceful daily life into a whirlwind of uncertainty and terror.

Yet, as the author himself indicates, “that I am alive proves that even in the darkest times there are decent people.” This book is both a personal testimony and a gesture of recognition for “those who retained their humanity in times of horror.”

With an eye for detail sharpened by his vocation as architect, the author narrates events with clean, simple lines, accompanied by fewer words than those on this page, understandable by a child, adolescent or an adult. As in an architectural blueprint, we see Diószegi street and the house in front behind a tall red fence from different perspectives. At times we view it subtly out of the corner of our eye, as if to avoid drawing attention to this place that harbors a refugee. The technical resource of parallel lines that converge in a distant vanishing point, accentuate some scenes, the sense of danger, aloneness and the smallness of the boy or perhaps how he feels.

The first action motivated by the urgent need to protect a vulnerable person was undertaken by Anna Meister when he took her son by the hand, crossed the street, and left him at the house on the opposite side. The Jewish community of Hungary had believed itself to be out of danger, but in April 1944 they would be enclosed in ghettos before being deported to unknown destinations. Anna, her sister, two nieces and her brother-in-law were among 15,000 Jews of Miskolc who would not see their city ever again.

Subsequently, and primordially, the Béres family took Adam into their modest home despite the danger to themselves. That in itself would have more than sufficed as a gesture of solidarity. However, when other neighbors reported to police the presence of a Jewish boy and he was taken to a transitory detention camp, the Béres did not give up. Fodor, the family’s grandfather, a short, slightly hunched gentleman with an enormous white mustache, traveled to the detention center to find him.

A young guard who listened to Fodor and looked for the child among the multitude was a point of light behind the barbed wire fence. The guards became convinced that the boy was not Jewish and let go with the grandfather. The sequence of denunciation, deportation and rescue was repeated a second miraculous time with another family member as his savior.

“It would be normal to say, we have done all we could. But they went and got me out again. Frankly, I can hardly believe it myself,” Adam Policzer remarks with a laugh. “If you read this in a novel, you think it is fiction. But here I am.”

Afterwards a family active in the resistance, who attacked German army convoys, protected him in their rustic rural one-room dwelling. Concealing a Jewish boy three months was also an act of resistance.

None of them – not his mother, the Béres family, the prison guard, nor the partisans- remained passive before the cruel reality around them.

A small, great detail explains how the boy could pass as non-Jew. Motivated by the hope of protecting their child, when Adam was born on November 11, 1938, his parents Anna Meister and Janci Policzer did not circumcise him, as is the Jewish tradition. Upon marrying they had made the strategic decision to convert to Christianity. Thousands did the same. Nevertheless, under racial laws Hungary enacted from 1938 to 1941, modeled on Germany’s Nuremberg Laws, the Nazis still considered them Jews.

At that political juncture in Europe, to be Jewish, gay, disabled, Romané or Seventh Day Adventist entailed marginalization, persecution, unimaginable mistreatment, and, ultimately, the prohibition of life itself. Thirty years later, Policzer would again know about detention camps. This time it was in the country where he reunited with his father (who had managed to flee Europe before countries closed their borders), grew up, went to school, got married and where his three children were born: Chile. At the safe harbor they thought to have found, the situation also changed drastically and suddenly.

This time around the persecution exercised by the state was not motivated by his origins but rather by the ideals that oriented his life. In both countries, these were systematic practices that the government institutionalized by allocating funds, infrastructure, and personnel to control the population through fear, in the case of Chile, in the framework of the interior security doctrine.

At the same time, in Chile as well as in Hungary, small gestures and great actions by family, political, religious networks protected lives during the years of terror. In fact, it was an act of solidarity on his part – an unsuccessful attempt to help someone enter an embassy to seek political refuge- that resulted in a year and a half in prison for Policzer.

From safe harbor to stormy waters

The next scene of Adam Policzer’s life is not part of his graphic memoir. The book concludes with the reunion between the son and his father in Santiago, with the majestic Andes mountains, hues of blue, gray and black, in the background. On the book’s last page, Adam and his wife Irene Boisier contemplate the possibility of telling the rest of the story in another book. What follows here is a preview of that second volume.

Adam Policzer always had a knack for drawing; he was also good at math. He chose a profession where he could exercise both gifts, earning a degree in architecture from the University of Chile in 1965. There he met Irene Boisier, his future lifelong companion and, in his words, the coauthor of this book. The acclaimed architect (National Award for Architecture of 2019) Miguel Lawner was their professor. Adam and Irene participated in Salvador Allende’s election campaign. When the socialist government took office, Lawner was appointed director of the Urban Improvement Corporation (Corporación de Mejoramiento Urbano, CORMU) and both went to work under him. Policzer, a Socialist Party member, was a leader of the union that represented CORMU professional staff. The country the Popular Unity (UP) government received had an enormous public housing deficit. It also lacked paved roads, street lighting, green space, schools, and neighborhood clinics, among other elements vital for people’s full development. It was an immense task, yet during the UP’s three and a half years, 158.000 public housing units were built.

At the book launch, Miguel Lawner said, “Adam assumed the beautiful responsibility that we all accepted with honor, that of designing and providing housing projects for low-income families. He passionately accepted that work as we all did our commitment, knowing that we were engaged in an exceptional experience.”

Those were the crimes, in addition to the unsuccessful action of solidarity, that earned imprisonment and exile for him, his director, and other members of the CORMU staff.

In December 1973 Adam Policzer was arrested and taken to Estadio Chile, a closed-roof sports stadium which had been a living hell for hundreds of prisoners in the first two months after the coup.[1] By the time Adam was brought there, its brutal regime had toned down and most prisoners had been transferred elsewhere. The remaining 200 slept on mattresses on the basketball court, with no chairs or any other kind of equipment. Mario Rodríguez, a new commander assigned to the site in February 1974, asked Policzer, the only architect imprisoned there, to design a wall to surround the parking lot so as to enable them to breathe fresh air and feel the sun. On Diószegi Street a high wooden fence painted red concealed the small house of the Béres family and the boy who played in the dirt yard. At times Adam would peek through the cracks to gaze at his house, now on the other side of the street, where he had spent happy moments. At Estadio Chile a wall built by his own hands and those of his fellow political prisoners prevented the outside world from noticing them.

For his leniency at a time when military commanders were expected to show an iron fist, commander Rodríguez was fired and retired with a low pension below his rank. “The man sacrificed his career to make the lives of those 200-300 human beings under his charge a bit more bearable. Once more I came across people like that,” says Policzer.

After Estadio Chile, his prison itinerary took him to Chacabuco, a living quarters for former nitrate miners in the Atacama Desert that had been abandoned since 1938 converted into a prison. His last stop was Ritoque, a working-class beach resort created by CORMU, which was reconditioned as a prison camp. There he reunited with his former director Miguel Lawner, who had been transferred from a prison island in the south. In 1975 Adam was released and warned to leave the country within two weeks. In Vancouver, Canada, his second exile, he rebuilt his life.

If there is no justice, there is memory

In 2007 Adam undertook a journey to dispel a doubt that had persisted all his life: the final destination of his mother. He was accompanied by his daughter Ana, named for the grandmother she did meet. The pilgrimage to rural places of Poland was prompted by information from a survivor who had been interned with Anna Meister, not in Auschwitz, as he had presumed, but at a forced labor camp near the village of Bocien. His mother was one of the 2,500 women who perished there whose bodies were thrown into a mass grave. At present the site forms part of the lovely country landscape.

Few Jews live in Poland today. In that light, it was significant to discover two memorial plaques that mark the place of the common graves that had been installed by local people who also make sure that flowers are always placed at the foot of the memorials. At a nearby high school, a teacher taught students about their town’s complicated history. This exemplifies what experts hold: recognition of harm caused from human rights violations not only to individuals but societies as a whole must transit from the sphere of the victims to that of entire nations.

In the post-Holocaust era, the principles of memory, justice and reparation were traced as a necessary route for enabling respect for human dignity to take root again in societies that have suffered ruptured democracies. There was no justice for Anna; nor was there for Adam. In that context, actions of historic memory – such as the memorials at Bocien, the renaming of Estadio Chile as Victor Jara Stadium site of memory, books like La casa del frente and the exercise of trans-generational memory by the entire community – are gestures of moral reparation. In current times with the rise of neo-Nazis in Hungary and Chilean negationists who recently celebrated the military coup, historic memory is more important than ever.

At Chacabuco and in Ritoque, Adam Policzer sketched what he observed. Those drawings comprise a graphic registry that will be the basis for his second book.

When asked what he hopes to convey to readers, Adam initially replies “There is no message.” Then he thinks about it and adds, “Well, yes there is. That I am alive is a message that there always are decent people. Often, I have asked myself what I would do if I were to find myself in the Béres’ position. How would I respond? I don’t know.”

The same question challenges every reader of La casa del frente.

Adam Policzer and his daughter Ana visit a monument at the grave where Anna Meister and 2,500 other women were buried in 1944.

[1] Built in 1969 in the heart of Santiago, Estadio Chile was an important arena for sports and cultural activities. The day after the coup, thousands of people were taken there and for the first time witnessed or were subjected to extreme repression. Among the 5000 people imprisoned at the place was singer, songwriter and theater producer Victor Jara, who in 1969 won first place in the Festival of the New Chilean Song held at that stadium. On September 16, he became one of 15 people killed there by the military. In 2009 the stadium was renamed Estadio Victor Jara.