The Berlin couple-dancing scene is an integral part of Berlin’s nightlife. Thursdays and Sundays at Berlin’s Soda Club (located at Kulturbrauerei), where you can dance pairwise on 5 different floors (Kizomba, Salsa Cubana, Mambo, Bachata, Zouk), are quite simply an institution. Open-air dance events are held almost daily on the Spree’s waterfront in summer, reflecting the dedication of this community: The events are free, the city’s best DJs provide their skills and people of all ages, from a wide range of cultural and social backgrounds move rhythmically in couples to the music. There are also annual festivals such as the Berlin Salsa Congress (for salsa), Berlin Kizzes (for kizomba) and Ritmo (for bachata), where dance classes and dance evenings can be attended for several days in a row.

By Yalira Santelmo

The pandemic, which has hit couple-dancing hard, has been a real challenge for large dance schools such as Mambita, Cumbancha, and Dolce Vita Dance – but they have successfully defied it with masks, HEPA filters, donations, and various precautionary measures. Dancing is simply an integral part of life – where there is life, there is dancing. This was a source of joy and a feeling of solidarity in Berlin, especially in times of such great interpersonal distance.

Whether tango, salsa, or zouk: couple dance is a form of cross-cultural communication in which no words are necessary: Through movement codes, music and role divisions, a framework is created in which each dancer can give free rein to their creative expression. By agreeing that one person leads the dance (the leader, traditionally seen as the role of the man) and one person follows in the dance (the follower, traditionally seen as the role of the woman), synchronized movements are made possible. This creates a process of emergence in which the dance not only represents the individual movements of two people but also draws a new, rhythmic picture. This opens up a wide range of creative possibilities beyond the actual dance steps.

Traditional role models are reversed or exaggerated (e.g., through clothing or traditionally masculine and feminine movement styles), elements from other dance styles are adopted or the mood of the evening is expressed in particularly emotional, reserved, or energetic movements that can be taken up and interpreted by each partner in constant interaction. In this way, each dance offers the opportunity to find an individual expression of strength, sensuality, and self-confidence. The result is a special form of empowerment that shapes the subjective experience of the dancers and the observers. Trust is necessary for this to succeed: Trust on the part of the follower that the body, which is allowed to be led, will be handled with care. Trust on the part of the leader that the follower will follow the movement impulses created by the leader.

But what happens when trust is abused?

In Berlin, there have been repeated reports of women being sexually harassed in the couple dance scene. In chat groups where dance enthusiasts exchange news about dance classes and dance events, these reports led to lively discussions. Opinions often differed widely – the incidents were either individual cases that were the responsibility of those affected, or reflective of an almost all-encompassing problem in Berlin that needed to be clarified from an organizational point of view, i.e. by organizers and dance teachers. A small group of dance enthusiasts have now taken the initiative and designed and carried out a survey at their own expense to get a more accurate picture of the extent of the harassment.

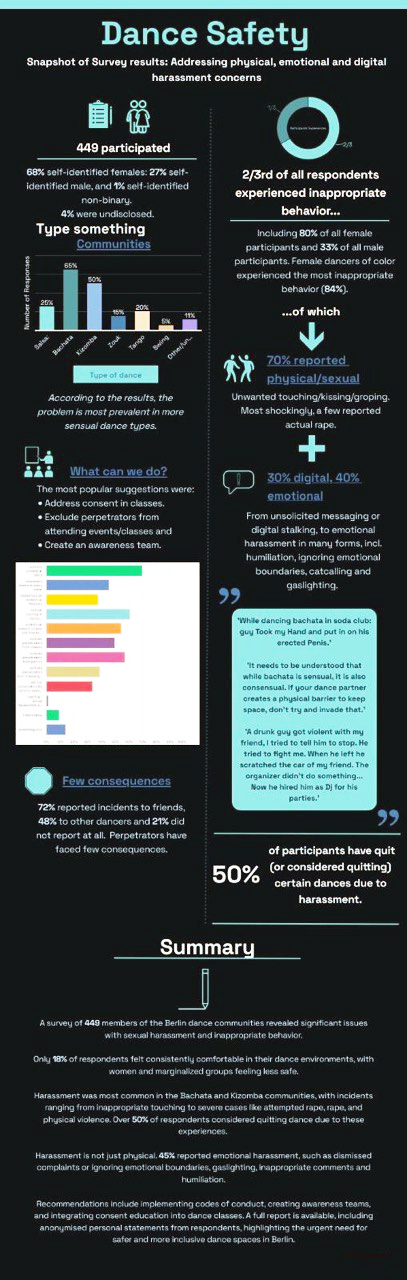

The results are concerning. Within just one week, around 450 couple dancers from a wide range of dance genres, from salsa to swing, completed the questionnaire (68% women, 27% men, 1% non-binary, 4% unspecified). Two-thirds of all participants stated that they had experienced inappropriate behavior – 80% of participating women, 33% of men – a clear disparity. Female POC (People Of Color) were the most frequently affected at 84%. The inappropriate behavior involved physical and sexual assault in 70% of cases, e.g., unwanted touching or kissing and even rape, followed by emotional and digital violence, e.g. gaslighting, stalking or catcalling (40% and 30% of cases respectively). For 50% of the participants, these experiences led to them stopping or wanting to stop dancing.

“Unfortunately, the result confirms our fears that this is a structural problem,” says one of the initiators. “The suspicion arises that misogyny is still a reality – also in Berlin. Women have to actively defend their boundaries, men have the right to cross them in the first place. This view is particularly poisonous in this constellation, where physical closeness lies in the nature of things.” In times of increasing social isolation, couple dancing offers the opportunity to get closer to other people in a regulated setting. However, if physical closeness is the main motivation and dancing is merely used as a vehicle for interaction with the opposite sex, this does neither the dance nor the responsibility for the dance partner justice. One of the participants describes: “While dancing bachata in soda club: guy took my hand and put it on his erected penis”. Examples like these show that dance etiquette is deliberately disregarded. An enjoyable evening is ruined in this way, a hobby becomes a risk to one’s well-being and safety.

How can this problem be solved? There are bouncers in larger clubs, but they generally offer little security. In the worst case, nothing is done at all according to the motto “statement against statement”. The fact that new events are constantly popping up, some of them privately organized, is particularly appealing in a city like Berlin, offering variety and new impulses – but there are big differences here in terms of the professionalism of the event and the attitude of the organizers and visitors towards women. Newcomers in particular run the risk of having bad experiences and are often unsure of what is “allowed” in the context of a dance, where assault begins and how they should best react. This is also reflected in the survey. Participants were asked what solutions would be desirable. 70% would like to see consent addressed in dance classes, just over 60% would like dance teachers, organizers and DJs to receive special training in this area and almost 60% would like to see people who are assaultive excluded from dance events.

It is particularly difficult to sensitize organizers and dance teachers to the topic, as the issue is often played down or kept quiet. Dancing is supposed to be fun, an escape from everyday life, so a discourse about violence is not very comfortable – especially when it comes to sought-after profit. An “awareness team” that is recognizable and can be approached at events, posters and publicity could help to raise awareness of the issue and make it easier for those affected to defend themselves. However, the most important thing is to hold the people who are guilty accountable – this can indeed mean exclusion from events or dance classes if someone is conspicuous for repeated assaults. In addition, there must be an active dialog at the event level to initiate a cultural change in the scene. Organizers must become allies of those people who suffer the most from assaults and actively protect them. Liliana de Lima, internationally renowned dancer, dance teacher and organizer in the field of Tarraxo and Urban Kiz (rooted in the original Angolan Kizomba), describes how this is a problem that goes far beyond Berlin. On her Instagram account, she says: “Women and men are not held to the same standards in the Urban Kiz and Kizomba social dance scene. […] Women are often described as easy or slutty if they simply enjoy their dances. Staying in a dance for more than 30 minutes or dancing with closed eyes can quickly become a reason for judgment. If you are a woman, that is. Meanwhile, the fellas are living their best lives. Multiple sexual partners in the same weekend are joked about and even encouraged if you are a male teacher/DJ/organizer. Cheating in your relationship is considered normal between many men in the scene, cause it doesn’t count when it’s at a festival, right?” This statement shows how deeply rooted misogyny is at an organizational level.

Only if we succeed in bringing about change on various levels can the couple dance scene become what it is supposed to be – a place of celebration of encounters, creativity, different cultures and humanity itself.

Text and translation by Yalira Santelmo

If you are interested in this topic, please get in touch: dancers4dancers.berlin@gmail.com