By Maxine Lowy

In a sample of the exuberant and infinite creative power of the human being, some 180 variants of two works, made by the same number of artists, cover the length and breadth of the walls of the Guillermo Núñez Art Gallery with color and texture. It is “Guillermo, qué quiere que le diga” (What can I tell you), an exhibition that opened on August 14 at the Anselmo Cádiz Municipal Culture House in the municipality of El Bosque, south of Santiago.

It honors not only the legacy of the National Prize for Plastic Arts, who died this past May 23, at the age of 94, after whom this cultural space was named, but also celebrates the two decades of his close collaboration with El Bosque.

Coinciding with the thirty-third anniversary of the creation of the municipality, the exhibition was organized jointly by the Illustrious Municipality of El Bosque and the Association of Painters and Sculptors of Chile (APECh). Soledad Bianchi professor of literature and the artist´s widow; Alejandro “Mono” González, muralist and his great friend; Alex Chellew, president of APECh; Antonio Donoso, municipal cultural manager, and Mariana Villouta, a

resident of El Bosque, participated in a discussion that was part of the opening ceremony.

Carlos Lizama, director of the Guillermo Núñez Gallery and coordinator of this exhibition, moderated the forum. The singer and pianist Milena Viertel, a music professor at the University of Chile, performed.

The title alludes to the catchphrase with which Mono González and Guillermo Núñez often began their frequent conversations, namely: “Guillermo, what can I tell you?” Likewise, in that spirit, by intervening a serigraphic copy of Núñez’s work, each participating artist dialogues with him.

As González recalls, “When I met Guillermo Núñez, he didn´t even know me.” Still in high school at the time, González went to plays with scenery and curtains designed by Núñez.

During the Popular Unity government, Núñez was director of the Museum of Contemporary Art and by then González´s iconography was already identifiable as the characteristic style of the Ramona Parra Muralists Brigade during Salvador Allende´s electoral campaign. Núñez invited the muralist brigades Elmo Catalán, Inti Peredo and Ramona Parra to organize a group exhibition at the museum. “This had repercussions for him,” says González, “because some academics were opposed to these kids who painted walls on the street being in a museum. It was kind of sacrilegious.”

When the dictatorship burst into the lives of Chileans, the painter´s rebellious spark led to four months blindfolded in prison at the Air Force War Academy. After regaining his freedom, in 1975, Guillermo Núñez installed a series of cages at the French Cultural Institute in Santiago. Each cage contained an object such as a piece of bread, a carnation, a shoe, and a blue, red and white tie hanging upside down as if from gallows. A young socialist party member named Sadi Melo managed to be present at that audacious exhibition that turned out to be quite ephemeral: 24 hours later, the exhibition was shuttered by agents of the dictatorship and the artist was taken away to the Villa Grimaldi detention and torture center. For Guillermo Núñez the artistic installation was an act of resistance; for Melo, who in 1991 became the first mayor of El Bosque, witnessing the exhibition was also a gesture of resistance.

The stark, sometimes chilling, abstract works that Guillermo Núñez began to produce during his exile in France and continued upon returning to Chile reflect the sheer brutality he experienced during that period. They also reflect a greater awareness of the need to denounce violence and an astonishment at the dehumanizing capacity of some people to inflict pain upon others.

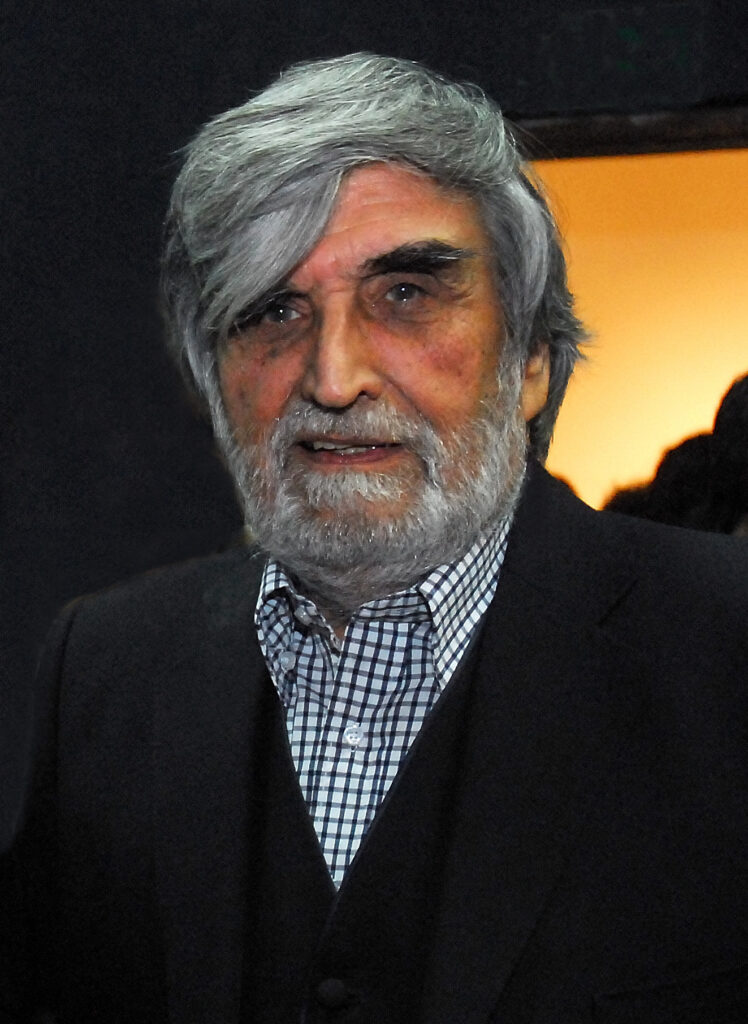

Manuel Carvallo

An Illustrious Neighbor

Ten years after being awarded the National Prize for Fine Arts in 2007, Guillermo Núñez received a recognition that greatly moved him: Illustrious Neighbor of El Bosque. Despite not living in this largely working-class municipality, many residents felt “his closeness and horizontality,” said Sadi Melo, who was mayor at the time.

Núñez´s presence in El Bosque that transformed him into a “neighbor” can be traced to the mid-90s. The driving force was Antonio Donoso, currently municipal cultural worker and former director of the El Bosque Casa de la Cultura. “The story of Guillermo Núñez in El Bosque is the story of the House of Culture,” says Donoso.

Founded in 1992, El Bosque’s Casa de la Cultura initially operated from a small, rented house without a gallery space. A few years later, Donoso paved the way for the first of many collaborations with Núñez. Alchemy, Art in the Streets was a project that Núñez had undertaken in Ecuador, Spain, the United States and in Colombia. In El Bosque it consisted of creating an open-air gallery with 20 large-format prints pasted onto walls along a busy avenue, with authorization from a bank and a factory. About twenty people from the neighborhood volunteered to paste facsimiles of Núñez´s works on the long walls and a nearby kiosk. The result was an open-air gallery, which invited pedestrians to pause to contemplate it, intervene, add graffiti, and even take pieces of the artwork. Later, several people who participated in that activity enrolled in painting workshops at the Casa de la Cultura and eventually formed the organizations Amigos del Arte (Friends of Art) and the Association of Painters and Sculptors of El Bosque.

Numerous exhibitions and special projects would later ensue. In 2002 the Casa de la Cultura named its gallery after Guillermo Núñez, a gesture that the artist once called “exaggerated affection." In 2016, the “Pintura a Domicilio, una Itinerancia Popular” (Paintings to your Home, a Grassroots Itinerary) project was launched. Through this project created by Núñez, 13 neighbors were chosen through a raffle to borrow one of his works to exhibit at their homes and show to neighbors.

Eventually, one of those houses was transformed into the Guillermo Núñez Community Gallery, a permanent art space maintained by Mariana Villouta and her young daughter Kenya. The project that began with a painting by the artist adorning their home, turned into a close friendship with Guillermo Núñez and his wife Soledad Bianchi. Mariana and Kenya live in Villa 12 de Octubre, in sector 1 of El Bosque, an area with a high rate of multidimensional poverty and the largest number of public housing projects in the municipality. During the tribute’s inauguration Mariana Villouta said, “I now realize that Mr. Guillermo was right. Art opens your eyes, opens your mind, […] changes your life. It helps equalize the gaps of inequality. This idea that I learned from him has become integrated as part of my life. It is the best legacy he left us in this peripheral place.”

It should be noted that in this municipality where socioeconomic precariousness affects many families, the Casa de la Cultura conducted a community consultation that revealed that the residents give priority not only to health, education and social assistance: they also ask for programs related to culture and art.

In an interview conducted in 2011 with Casa de la Cultura staff, Guillermo Núñez commented, “Since the 1990s we have been together inventing things. Every time I dream up some crazy idea, you guys have always enthusiastically agreed.”

The municipality of El Bosque’s cultural policy is reflected in part in the vast array of workshops and programs offered free of charge by Casa de la Cultura. Its cultural outlook coincides with the cornerstones of artist’s view of art: territoriality, democracy, participation and human dignity, with a social message that transmits the value of human rights, historical memory and solidarity. Furthermore, by promoting the cultural enrichment of the urban periphery, both Núñez and El Bosque represent a counterweight to market-oriented, elitist culture and art.

Manuel Carvallo

The Exhibit

Through the APECh, the Casa de la Cultura and the University of Chile School of Fine Arts, more than 200 reproductions of two serigraphic prints by Guillermo Núñez were distributed to artists to intervene with whatever techniques they wanted. On a white background, one print features two large amorphous black smears with splashes of paint, cut by thin white lines and small planes of light, probably made with Indian ink and a white corrector pen. Near the lower left corner is the signature without capital letters of the painter Guillermo Núñez. The interpretation is in the eyes of the beholder.

The 180 copies that artists returned with their respective interventions amaze with their diversity of colors and techniques, a few even converted into sculptures. Some carry handwritten replies to the question posed by the exhibition’s title, with reference to the dictatorship, human rights, love, and other themes. Some scribbled personal messages on the paper, as was the case of Kenya who wrote, “I met Guillermo Núñez when I was 6 years old.”

Carlos Lizama, coordinator of the exhibition shares what he sees in the gallery. “It is a great constellation that envelops you. Upon entering the room, it feels like you have entered another space, a different dimension. You can observe this atmosphere from the micro to the macro levels. You observe this vast constellation, but you also can see the micro of each fragment that comprises the whole. And within each work, one observes many more elements. In its entirety. it is a constellation of memory that honors Guillermo Núñez.”

When the exhibition concludes on August 28, it will begin touring through various regions of the country. Local artists from those places will add their own interventions and interpretations as a tribute to Guillermo Núñez.

Some voices have criticized what they consider to be a lack of respect and irreverence in intervening in a work created by a National Arts Award winner. However, Soledad Bianchi, the artist’s wife, insists that it is “totally consistent with his concept of being an artist” and his desire to encourage people to express or discover their creative streak. More than once, Núñez himself provided copies of his works to be intervened, such as in an activity with children at Chile’s Museum of Fine Arts. He sought to spur “dialogue” through his art and “he would have loved this exhibition,” she says.

Alex Chellew, president of APECh, agrees. “From his work as base, another work would emerge [with the intervention of other creators]. That was what he called the game of interpretation.”

For El Bosque city council member Simón Melo, the exhibition reminds him of the concept of alchemy, at the heart of the initial collaboration between Núñez and El Bosque. “This exhibit evokes a constant transformation that does not end with one piece of art. Like the song [by Jorge Drexler] nothing is lost, and everything is transformed. It is art that lives and transcends beyond the artist.”

When Guillermo Núñez and Soledad Bianchi arrived in exile in Paris, they formed a close friendship with the writer Ariel Dorfman. Dorfman wrote a message for the opening ceremony that was read by Pedro Sánchez, printmaking professor at Finis Terrae University. The message concludes as follows: “Now they tell me that he has died, and I don´t believe them, I don´t believe them, I don´t believe them.” To this, Mono Gonzales replied, “Guillermo Núñez is not dead. In this place that houses his work, Guillermo is present and very much alive.”

Mariana Villouta and Kenya